Seeking Paths from Vulnerability to Safety in Tornado Hot Zones

A deadly F-4 tornado near his childhood home propelled Tim Marshall into a 45-year career mixing meteorology and engineering on a mission to build back (and forward) safer.

DONATE: Accuweather has a useful list of organizations helping tornado victims.

NEWS update, 12/17/21, 6:05 p.m. - The St. Louis Post-Dispatch has verified and published text messages between an Amazon driver and dispatcher showing no indication that the company had a clear, established protocol for when a tornado siren sounds. This exchange is particularly haunting:

Dispatch: Just keep delivering for now. We have to wait for word from Amazon. If we need to bring people back, the decision will ultimately be up to them. I will let you know if the situation changes at all. I’m talking with them now about it.

Driver: How about for my own personal safety, I’m going to head back. Having alarms going off next to me and nothing but locked building around me isn’t sheltering in place. That’s wanting to turn this van into a casket.

The article has Amazon's response. It is not reassuring.

Today's post:

I first interviewed Tim Marshall in 2002 while reporting a story on the terrible damage wrought in La Plata, Maryland, by a deadly tornado with winds hitting 158 miles per hour (F-4 on the Fujita scale at the time). Using his training in both meteorology and engineering, Marshall was then, as now, investigating the intensity of the twister but also, with equal vigor, the weaknesses of the structures it encountered.

What makes a tornado a disaster is not the storm, but the cost in deaths and destruction. And that toll is a function of both wind strength and the vulnerability of the structures and communities in harm's way.

"Pure wind doesn't do the damage,'' Marshall told me for my New York Times story. The quality of construction determines if a building disintegrates into deadly missiles. ''The churning debris acts like a blender,'' he said. In and around La Plata, many houses - old and new - did not appear well built, he told me, with few fastenings linking roofing to frames, frames to foundations.

We talked again many times in the intervening years, particularly when I reported on the EF-5 twister that ripped apart Moore, Oklahoma, in 2013 (EF because the scale became an "Enhanced Fujita scale in 2007.)

Yet again, even in a city less than 10 miles from the National Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, far too many homes and other structures were not built with human survival in a tornado in mind. I won't soon forget this image of an all-too-rare tornado shelter amid the wreckage there.

And here we are again.

I turned to Marshall for my previous Sustain What dispatch, which focused on the 14 deaths in big-box-style industrial structures - a candle factory in Mayfield, Kentucky, and the Amazon shipment center in Edwardsville, Illinois. Marshall had been in Mayfield and another area assessing damage as a volunteer in a federal engineering analysis.

There's much more to write about why those facilities had not adopted the clearcut, simple life-saving designs and protocols that protected all 150 workers when a F-4 tornado destroyed a similar-size company in 2004. And I'll be writing on the "expanding bull's eye" of residential growth in tornado country, as well.

But here I want to offer a closer look at what propels Marshall and so many like him working doggedly to spur changes in community and commercial design and practices.

They are, like I am, tired of the human "blah, blah, blah, bang" form of risk management that still seems to dominate.

Tornado risk is shaped on the ground, not in the climate

With or without climate change, tornado losses are poised to rise dramatically because big regions of America’s tornado hot zone have built deep vulnerability resulting from a mix of rapid growth and the human tendency to discount threats that have a low probability but disastrous potential.

Below you can watch our conversation and read transcribed excerpts (condensed and reorganized a bit for flow). Then weigh in!

I'd particularly appreciate hearing from folks in regions with outsize risk from tornadoes as well as hurricanes and other hazards. What best practices have you seen that can make a real difference, both for residential areas and businesses?

Andy Revkin - Just tell us a little bit about how you got to be who you are.

Tim Marshall - I've been interested in tornadoes and tornado damage since I was a kid. I had an EF-4 tornado hit my hometown and I saw the carnage firsthand. I had no clue, at 9 years old, what was going on here. When you're 9 and 10 years old, you're in this curious stage and I already loved science. I was already into weather before the tornado. My parents, in fact, asked me the Christmas before what I wanted for Christmas. I said a barometer.

After the tornado, I did a science fair project for the school district on tornadoes and won the top award. I kept on getting encouraged. The teachers that I had were phenomenal. They saw that I was interested in science and they encouraged me to pursue that. And that's what it takes. You know, it takes your peers, teachers, parents to encourage you.

I read everything I could. I wrote to media people. They responded. I wrote to Dr. Fujita [Ted Fujita, the pioneering meteorologist who devised the F scale of tornado intensity] and he sent me a bunch of colored maps that I posted on my wall. I was in seventh heaven. He was in Chicago, and so was I. I went down and met him for the first time in 1974, right after the Super Outbreak, and he gave a beautiful talk. I still have the notes from that talk.

Explore Ted Fujita's tornado science via this University of Chicago post.

I was inspired by Dr. Fujita and wanted to live a similar life. He's a trained engineer and meteorologist, and I wanted to do the same thing. So here I am as a as an engineer and meteorologist, been surveying damage for 45 years. So it just takes a spark, doesn't it. It takes somebody that you look up to and is a role model. And then it just keeps going.

AR - Describe the areas you visited this week.

Tim Marshall - I looked at two areas, Mayfield and Dawson Springs. These are dense areas, lots of different building types. And that's what we're interested in is the different kinds of buildings and how they perform. I volunteer on an American Society of Civil Engineers committee for estimating tornado wind speeds. And we do that from damage indirectly.

Mayfield from the air; the three red-walled structures stood up where others fell. (Tim Marshall)

TM - Those are three storage buildings I looked at in the right side there, which did quite well, actually, because they were anchored down to a slab and they had good cross bracing in them, with what we call partition walls. But you can see the destruction there, all around it.

AR - Did you visit the destroyed candle factory?

TM - I went down and looked and walked around the candle factory. And studied the steel structure.

AR - Was there any indication that there was a tornado shelter within the complex?

TM - The word shelter is used loosely. I was talking with several people there and [they said] there are several areas in the plant where you can go to - restrooms, for example, some workbenches that you could get under. But these are not what I would call safe room style.

They said they had some sort of a safe room that was 12 by 12, but you've got 100 plus people. And then I asked for the construction of the safe room and it was just cinder blocks which collapsed. And three people that went in there died.

So it's like it really wasn't what I would call an NSSA, National Storm Shelter Association-approved safe room. When we say safe room, it is steel-reinforced concrete with a concrete roof. That's what a true safe room. So the term shelter is relative.

When 150 workers walked away from tornado wreckage

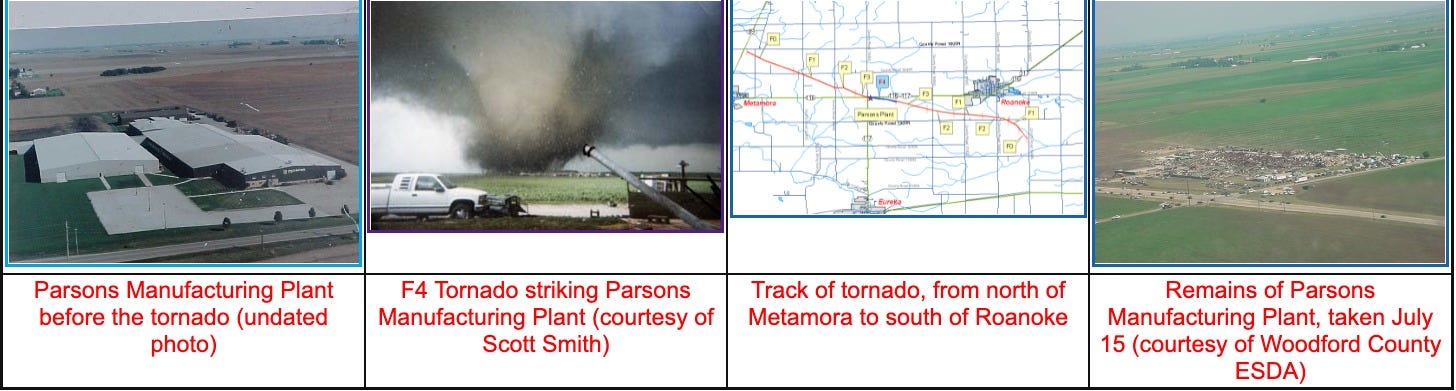

AR - Let's go to 2004, when a powerful storm that became an F-4 tornado destroyed the Parsons Manufacturing plant. The company was pretty remarkable in the sense that they did some things ahead of time that one would think what would be the norm now because of the clear cut outcome in this case was extraordinary.

It had these shelters - steel-reinforced concrete areas. It's remarkable to me that no one was injured out of 150 people at the plant that day. What was different there? You also pointed to those buildings a minute ago that stood the test there in Mayfield. What makes the difference?

TM - It's a great example and it shows that you can save everybody. I wish that could be done across the board. But it's a lot of money to have safe rooms put in the building like that. So you're looking at hundreds of thousands of dollars for that, and that has to come from somewhere.

It's like, do you want a Christmas bonus this this winter or do you want a storm shelter? And the odds of a tornado hitting a manufacturing plant like this is very remote.

AR - The other thing that was clear in this case, when you read the detailed reports, it's not just the structure. There's four components to this. There's the having a defended structure. There's having situational awareness. In this case, they actually trained employees so that when there was a radio warning one of them would go out and be a spotter. They did drills at least twice a year, and they had it evaluated. This isn't just about a room?

TM - That is extremely important because any one of those things that breaks down and doesn't happen, then you have a catastrophe on your hands. So it is a series of links, like links in the chain, and you've got to have every link just as strong as possible.

So I think this is kind of a model for other facilities to take a look at and say, 'Hey, you know, these tornadoes, although they're rare, there are no safe places in these big-box places. Big-box buildings don't have really any safe areas. They may have a designated safe area, but a bathroom or a closet, something like that, it won't provide the ultimate protection.

Big-box buildings don't have really any safe areas. They may have a designated safe area, but a bathroom or a closet, something like that, it won't provide the ultimate protection.

AR - So here's the big question: Why in the world is what we're looking at here - a building that was destroyed, sadly, but everyone kept safe - not the norm, especially for new construction? I assume this is still not the norm, even though this story is so compelling, right?

TM - Oh, it's not the norm, absolutely not the norm. Mr. Parsons [the owner of the factory destroyed in 2004] is to be commended for what he has done.

He saved 150 lives.

So he's a hero in my book. So it's amazing that you have to take that initiative because the building codes don't mandate that you must put in a safe room in every warehouse.

The building codes are a minimum design and the minimum design is these manufacturing plants are built no better than your house, I mean, they're built to the same building code.

So they take a lot of wind load and they obviously don't do very well. They're not meant to be shelters in the first place. Right. And you know, you get this EF-4 tornado, with wind speeds of one 180 miles an hour when they're only built or 90. Well, that's four times the forces a building was designed for.

The buildings performed as we would expect them to with a wind speed that that goes four times over design. That's what going to happen. Complete collapse. These manufacturing plants, they're in bays. They have a steel frame and it's connected to another steel frame by purlins and girts. So they reinforce each other. So when one gets overloaded, it transfers that load to the next bay and that transfers along to the next day and that transfers the load the next day. And guess what happens a domino effect? Boom. Boom, boom, boom. Boom, boom, boom. So the whole building collapses.

Collapsed Amazon fulfillment center in Edwardsville, Kentucky where six workers died (National Weather Service photo).

AR - I've written about this issue of expanding vulnerability, what Steve Strader and Walker Ashley call "an expanding bull's-eye" of vulnerable structures that's been booming in the Southeast and some of these other areas. They mostly have focused on housing, modular homes, mobile homes. Is there a similar bull's eye being built through this big-box industry?

TM - The targets are getting bigger. More and more people are getting in harm's way here. And you know, they need to eat. They need to have clothing. And so you're going to have to have the demand with feeding a lot of people, clothing a lot of people. And that's why the move is to big box. That's where they can make lots of food and lots of clothes in these facilities. But they also put the employees at risk if they don't have adequate shelter.

Tough tradeoffs boosting safety and profit

AR - OSHA and NOAA together are trying to fill some of these gaps for employee safety. But we're always playing catchup. Does it always take a direct hit for some chunk of United States real estate to say, oh, we need to do this too?

TM - We live in an action/reaction society. I mean, preparedness is out there. It's up to people like Mr. Parsons to to go beyond what is mandated and do it himself because he had an experience with tornadoes when he was young. And that's usually what it takes is that he went way above and beyond what normally is a course of action and is to be commended.

But to try to mandate that, you're going to get a lot of pushback because it costs money to do this right.

And they don't have these safe rooms over in Mexico. They can make those far cheaper there than they can here. So it's like, what are you going to do? You going to take jobs away from people for a safe room? It's a dilemma, and it's no easy answer here.

AR - I'm really glad you're on still on the case.

TM - I've always pushed for building better because I've seen the destruction with the countless number of surveys I've done. The state of Florida has the best building code in the nation in terms of wind resistance. And why can't we do that for the rest of the U.S.?

We are still building buildings the way my grandpa was building buildings. Why have we not been able to learn by this and just anchor these buildings down properly?

And you can resist it and say, well, you know, these tornadoes are so violent, there's no way you can withstand building that, and that's true.

So let's then turn our attention to protecting the occupants like Mr. Parsons did.

AR - Maybe there's a formula for cost effectiveness - to build a reinforced restroom area that's maybe not as costly as what [Parsons]. Is someone looking at a way to modularize this? I would think if anybody could do this at scale, it would be a company like Amazon.

TM - Oh, absolutely. And you know, restrooms are one place, but also like a cafeteria. You're going to have hundreds of people in these buildings and you can't fit them all in a restaurant. So it's having something like a cafeteria. If you can create a market for that and sell that, yeah. I mean, that can be easily done. Yes, it takes up some floor space, but you can put that at the end and it has a concrete roof, and very few windows that looks like an approved shelter. So if it's an approved shelter, there you go.

AR - All right. Well, if Jeff Bezos can send rockets into space, maybe he and his company can do something like set the standard for this kind of part of a facility.

TM - Good point, Andy.

Watch and share our discussion on Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter and here on YouTube:

Seeking Paths to Safer Communities and Businesses in Tornado Hot Zones

My story on how Parsons Manufacturing avoided any deaths or injuries when the 2004 Roanoke tornado destroyed the 250,000 square foot plant with 150 people inside: When a Killer Tornado Destroyed a Sprawling Factory and Nobody Died - Lessons for Amazon

Resources

Community Storm Shelter Design: A Marriage of Codes and Artistry - illuminating article on same rooms and shelters big enough for an Amazon-scale facility, published by the Texas section of the American Society of Civil Engineers

Safe Rooms for Tornadoes and Hurricanes - Federal Emergency Management Agency design and construction guidance for both residential and community safe rooms

As this guide says, since such guidance was first published in 1998, "tens of thousands of safe rooms have been built, and a growing number of these safe rooms have already saved lives in actual events. There has not been a single reported failure of a safe room constructed to FEMA criteria."

Support Sustain What

Thanks for commenting below or on Facebook.

Subscribe here free of charge if you haven't already.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues!