When a Killer Tornado Destroyed a Sprawling Factory and Nobody Died - Lessons for Amazon

As wreckage is scoured & victims mourned, big-box businesses in tornado country would do well to follow the example of a company that was destroyed in 2004 but lost no one & built back even better.

DONATE: Accuweather has a great list of organizations helping victims.

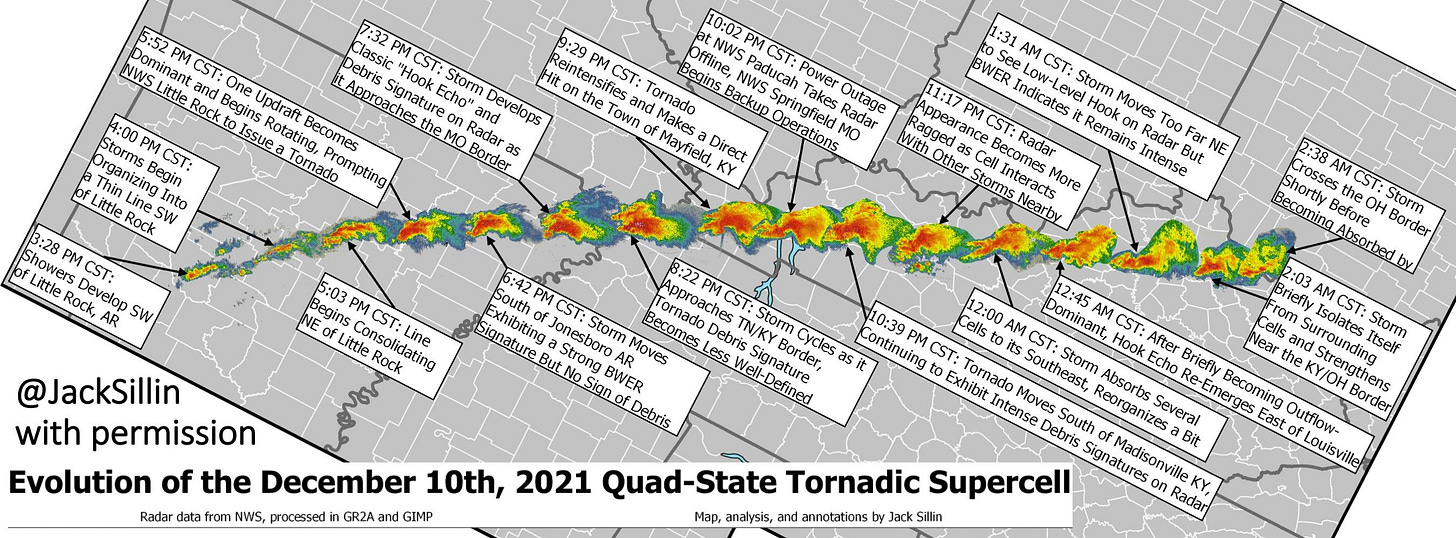

It's still the earliest stages of search, recovery, grieving and investigation following the deadly December 10-11 tornado outbreak. The catastrophic centerpiece, currently called the "quad-state supercell," could still possibly break a nearly century-old record (219 miles) for the length of a tornado's scar on the ground.

The damage and loss of life (at least 74 deaths at last count just in Kentucky) are widely dispersed and both official announcements and media coverage have yet to fully encapsulate the scope of the history-making tragedy. Appalling tragedies are emerging, including the loss of 11 people inside three homes on a single street, Moss Creek Avenue, in Bowling Green, Kentucky - a toll including seven children, two of them infants, according to the Associated Press.

On December 15, President Joe Biden visited Mayfield, Kentucky, one focal point in the disaster zone, touring wreckage, consoling victims and releasing fresh federal aid for the recovery - a too-familiar duty of presidents these days.

When I wrote for The New York Times, I covered tornado tragedies starting with a rare super-potent EF-5 tornado in Maryland in 2002. In the following years, I explored a host of ways to cut the tornado toll in households in harm's way. It's a tough challenge, linked with poverty and housing policy and much more.

The other focal point of urgent concern elevated by the latest calamity is deadly vulnerability of workers in modern commercial buildings that were hit. Their deaths were an avoidable part of this sprawling tragedy, by many accounts.

Big facilities without true safe rooms are death traps

As you undoubtedly know, six people were killed when one of Amazon's huge five-year-old fulfillment centers in Edwardsville, Illinois, partially ripped apart after suffering a direct hit from a tornado with winds that reached 150 miles per hour in its brief four minutes and 3.65 miles of existence.

That appears to be the second-biggest death count in a business in the outbreak, with eight workers killed in a large candle factory when the quad-state supercell churned across Mayfield at peak strength.

These incidents both show that big-box-style structures that are blossoming around critical consumer markets and transportation hubs across the United States are not fit for purpose in regions at risk from tornado-strength winds - at least not as currently outfitted and operated.

This presents an acute challenge - and opportunity - for the retail giant Amazon and other companies that, in rapidly expanding operations in the heartland, have boosted ailing economies but, as these tornadoes glaringly show, are failing to keep employees safe.

In-depth investigations have been launched to determine what mix of tornado ferocity and lapses in design and protocols led to these and so many other lamentable losses.

Many tornado-safety and engineering veterans say that while it's impossible to avoid all deaths across a variegated region hit by a tornado outbreak, it is absolutely possible to save the lives of everyone in a commercial facility like those that were destroyed.

This might sound grandiose and unrealistic, but it has been done - in a factory with similar scale, but built and run very differently.

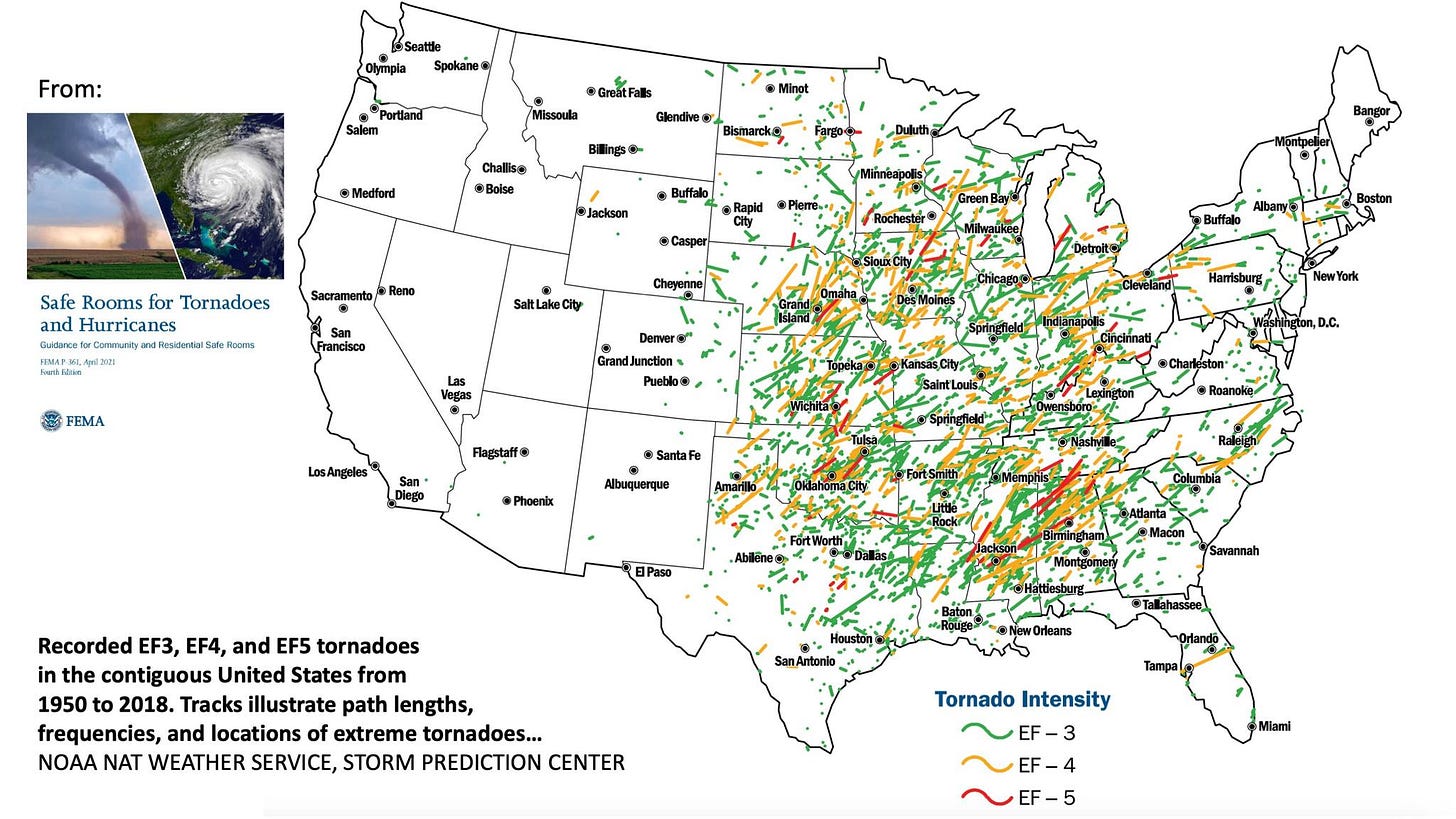

A case study in protecting workers amid tornado destruction

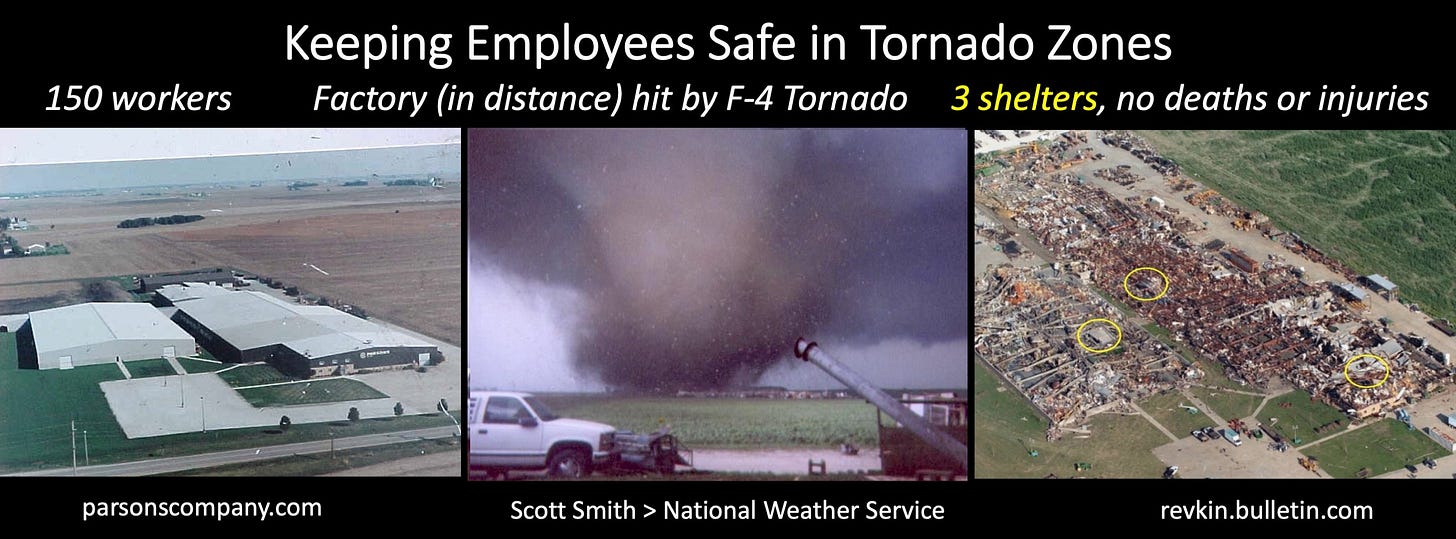

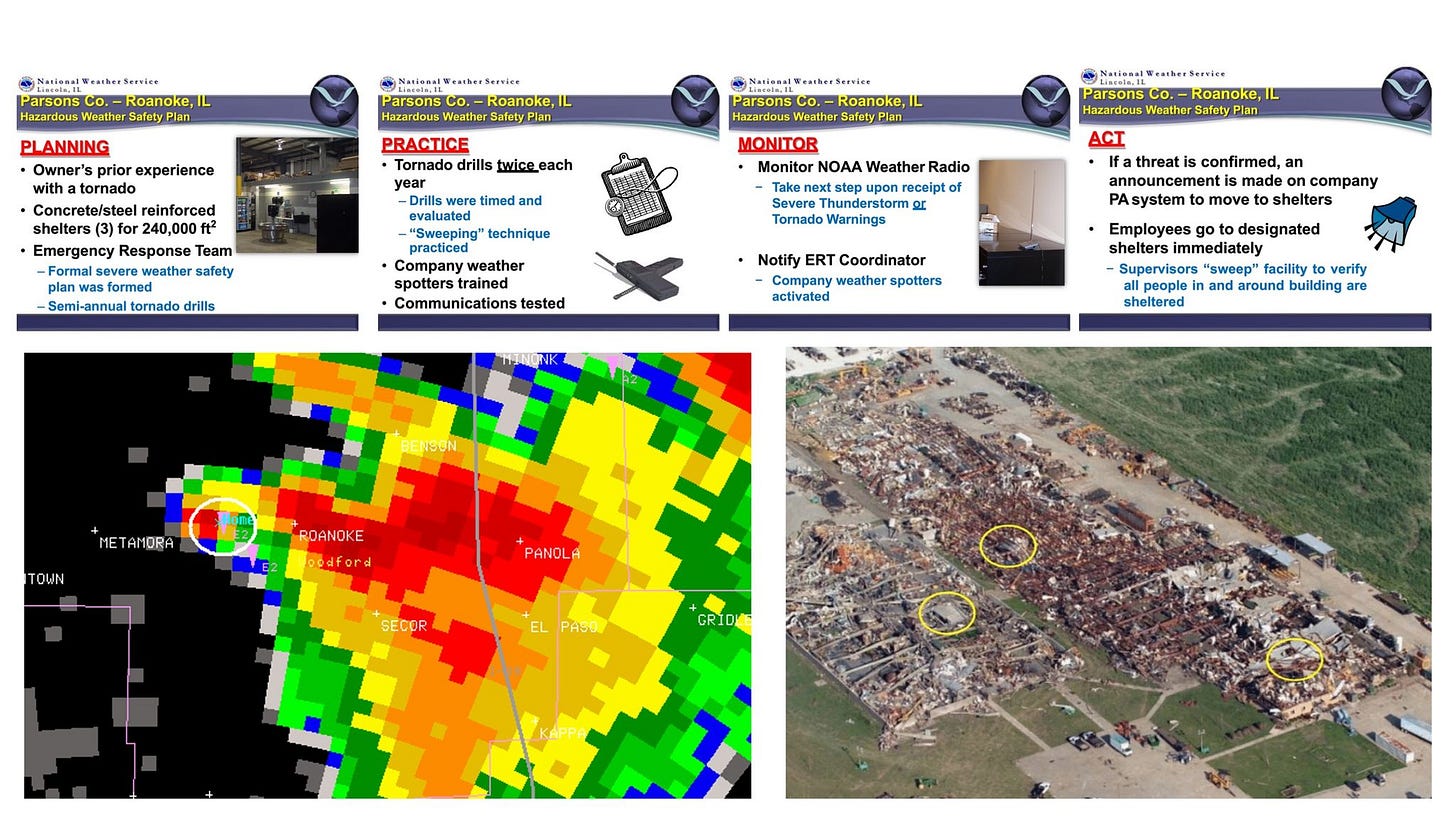

A vivid case study in tornado safety played out 220 miles north of the Amazon tragedy on July 13, 2004, outside Roanoke, Illinois. A tornado at EF-4 intensity, with winds between 210 and 240 miles per hour (vastly more destructive than the EF-3 that hit the Amazon facility), ripped apart the recently-expanded 250,000-square-foot metal-working and assembly plant of Parsons Manufacturing, with 150 workers and visitors inside.

And no one was killed or injured.

That outcome was no stroke of luck. It was the result of the owner, Bob Parsons, designing the plant and company protocols from the beginning with tornado safety in mind more than regulations or codes on the books.

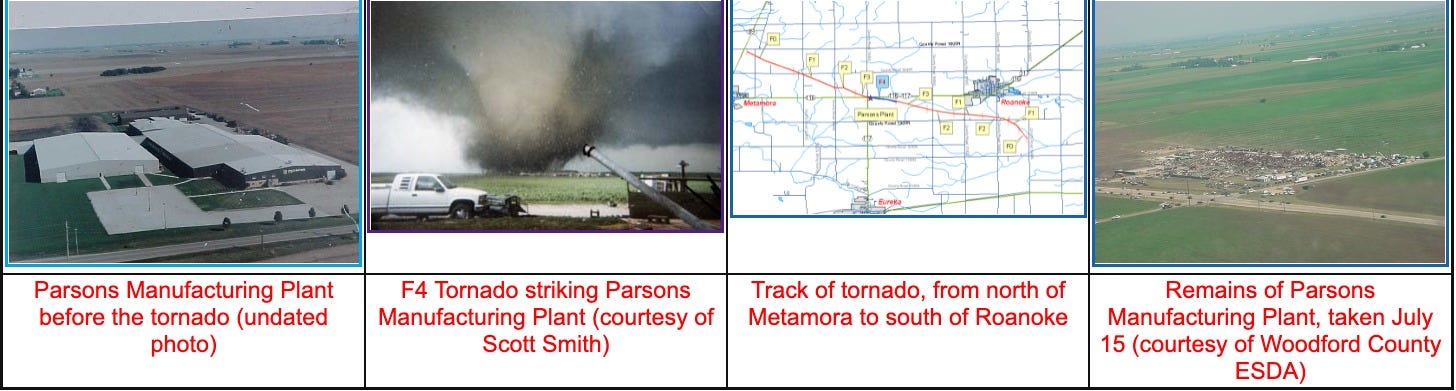

The Parsons building, when struck, had three distributed storm shelters (doubling as rest rooms), built of steel-reinforced concrete, making it easy for employees anywhere in the plant to seek safety when warned.

But Parsons also had a thorough and active weather-emergency response team with procedures developed with help from the National Weather Service and independent safety contractors. The team included an employee trained in tornado spotting who was sent out to assess the track of the tornado when the first weather radio alert was received.

Managers were trained to sweep the entire plant swiftly after the take-cover alarm was sounded, to be sure all had responded.

Steve Smedley, a photographer, was among the first on the scene. In an interview, he recalled encountering a flow of shocked, exuberant workers emerging from the wreckage. A welder, Bill Reed (in the photograph above), told him how he and fellow employees took cover in the reinforced restrooms: "We all walked out, together, everyone's safe. We were in the bathrooms, and we all walked out. Wow!" (Read and see more in the Pantagraph photo package published on the 17th anniversary of the tornado.)

When Parsons rebuilt in 2005, the result was a 300,000-square-foot facility on the same site, now with seven reinforced storm shelters. (A second factory has followed.)

In a video interview, Tim Marshall said Parsons "is a hero in my book," not only for saving 150 lives through careful planning and investment, but by clearly showing how a focus on core principles of disaster risk reduction is vastly more effective than simply looking up, and hewing to, building codes.

"The building codes don't mandate that you must put in a safe room in every warehouse," Marshall said. "The building codes are a minimum design. These manufacturing plants are built no better than your house; they're built to the same building code."

Marshall said the key is a holistic approach to tornado (or other) risk, meshing the safest design with practices that foster alertness, responsiveness, and a culture of continual assessment.

"If any one of those things breaks down and doesn't happen, then you have a catastrophe on your hands," he said. "So I think this is kind of a model for other facilities to take a look at and say, 'Hey, you know, these tornadoes, although they're rare, big-box buildings don't have really any safe areas. They may have a designated safe area. But a bathroom or a closet, something like that, it won't provide the ultimate protection."

Insert, December 19 - A remarkable comment posted below by Meghan Michelle Blake deserves to be highlighted here:

"My mother lived through the Parsons Tornado. I’ve been in and out of the old and new building my whole life. The new tornado shelters in the new building, you can feel the protection of those safe rooms in the new building. It’s so solid you can feel the difference in the atmosphere. I owe Bob Parsons my mother's life. And i wish that the requirements for storm shelters were up to the standards that Bob placed."

A start: real storm shelters or safe rooms in big structures

I would love to help connect Bob Parsons and Tim Marshall with Amazon's team as the company assesses next steps.

The issues and opportunities that Amazon, in particular, must weigh extend well beyond this one demolished fulfillment center. The company's far-flung, and rapidly expanding, network of large sorting and storage facilities spreads across a wide swath of tornado-prone states. You can track them on a website maintained by the supply-chain consulting firm MWPVL International.

Amazon's technological and financial might, along with the power of scale, mean the company could help develop a leading-edge standard for modular, cost-effective safe rooms in sizes suitable for these big operations.

If you sift Amazon.com now, you can actually find and buy a $10,493 home-size safe room good for four people. Maybe companies can someday order commercial-scale variants. (Or maybe this is Elon Musk territory.)

Marshall noted there are already standards, and plenty of examples in schools and other facilities where such protection is already required. Here's one in a middle school in Seneca, Missouri, as shown in a Federal Emergency Management Agency report:

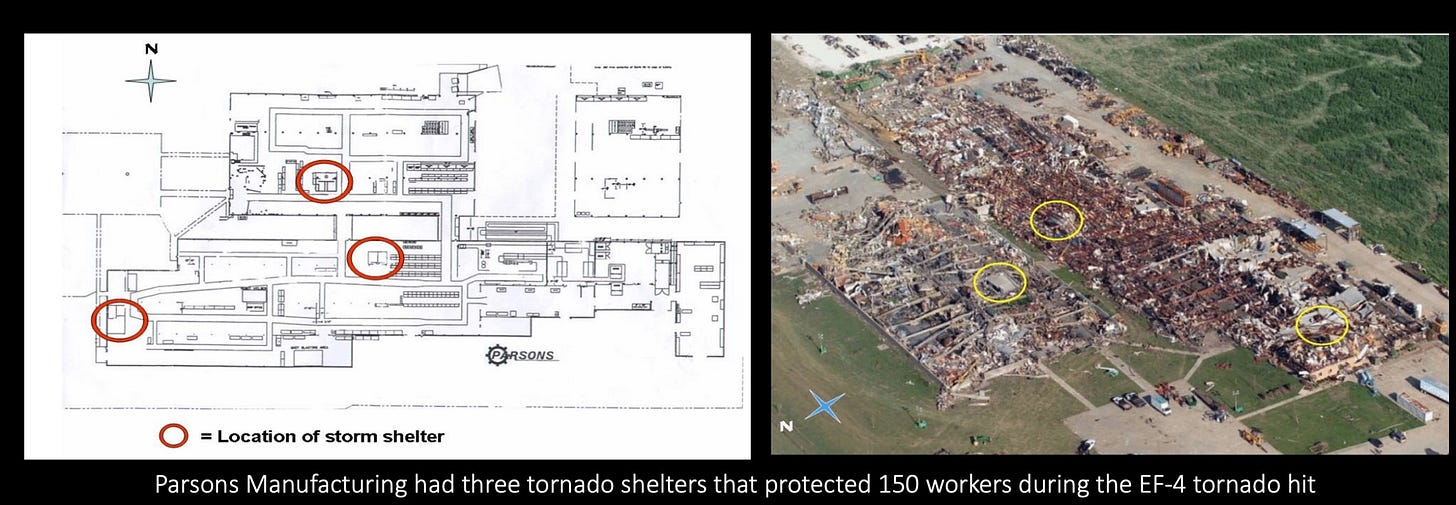

Here's a map from the National Weather Service showing vividly where the hazard is greatest:

From Safe Rooms for Tornadoes and Hurricanes - FEMA.gov

Marshall noted there's no way economically to justify the extra expense of safe rooms everywhere. But the map shows how a company like Amazon can prioritize.

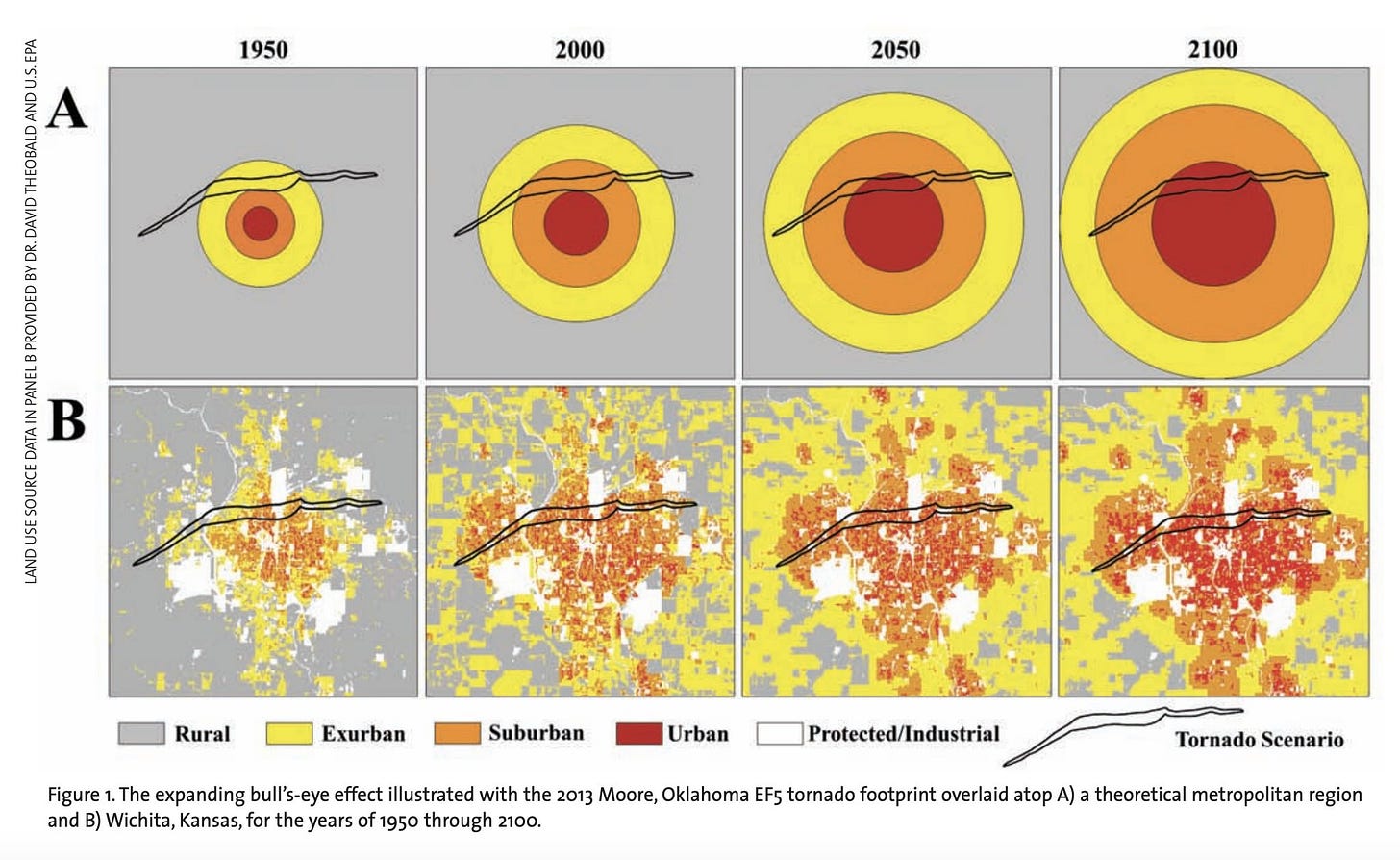

If it sticks with business as usual, the company will simply be building an "expanding bull's eye" of vulnerable enterprises across that same map. (This brilliant term was coined by the hazard-focused geographers Walker Ashley and Stephen M. Strader.)

I reached out a couple of times to Amazon's press office with questions early in the week and will publish any input that comes in. I also reached out to Walmart, which has a similarly vast footprint, to see what their practices are. Just because this storm hit Amazon, that doesn't mean the next one will, too.

An "expanding bull's eye" schematic shows how sprawling development expands how much housing and commerce is exposed to a hypothetical tornado. (Walker Ashley and Stephen Strader)

Deadly "safe areas"

For the moment, the official probes continue to unfold, focused both on Amazon's Edwardsville disaster and the candle factory, owned by Mayfield Consumer Products.

In both cases, elected officials and surviving employees have described a lack of adequate safety measures. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has opened an investigation into the Amazon deaths. Kentucky worker-safety officials have done the same with the candle factory.

Troy Popes, the chief executive of Mayfield Consumer Products, made a compelling argument on Fox News on Sunday that more lives would have been lost if managers hadn't shepherded employees to shelter inside the factory’s bathrooms, which he said had windowless concrete walls and a steel roof.

I asked the tornado engineer Tim Marshall what he saw and heard when he toured the candle factory site. It was particularly rough, he said, because of secondary impacts from the vast volumes of boiling wax that flowed lava-like from the destroyed building.

His focus was on structure, and there were problems. "They said they had some sort of a safe room that was 12 by 12, but you've got 100 plus people," Marshall said. "And then I asked for the construction of the safe room and it was just cinder blocks, which collapsed and three people that went in there died."

The wreckage of the Mayfield Consumer Products candle factory (Tim Marshall)

At a news conference early this week with Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker and others, Amazon officials said that the Edwardsville building had what they described as a "safe area," but specified it was not a "safe room." A safe room is a specific kind of shelter, typically with steel-reinforced concrete walls and ceilings, that tornado experts see as the only sure protection from tornado winds that can top 250 miles per hour.

That is what Parsons Manufacturing had, and has today.

Kelly A. Nantel, Amazon's director for national media relations, centered her statements on the company's adherence to building standards. "We know that the building was constructed consistent with code and so obviously we want to look at every aspect of this,” she said.

To me, that focus on code is precisely the problem.

The core reality, hardly a mystery to disaster experts, is that building and worker-safety codes in America simply haven't kept up with best practices if your goal is to keep workers safe from extreme-weather events.

You don't have to dig deep to see this dangerous gap.

On its website, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has a voluminous set of pages devoted to advising homeowners and small businesses in areas subject to extreme tornado winds to consider building safe rooms.

In such areas, the website explains, "[B]uildings may be built in accordance with modern building code requirements, but still not be able to withstand winds from extreme events and provide life-safety protection for those inside."

A primer for businesses in tornado zones

I also reached out to Ed Shimon, a longtime senior meteorologist for the National Weather Service in Illinois, who is frequently on the road giving seminars for communities, companies and others on how to design facilities and prepare for the worst – often using the Parsons tornado survival story as a talking point. Here's a link to one of the Powerpoint presentations he and others have used

How to build a business that can survive a tornado (National Weather Service)

The talks are not just about building tornado-resistant structures, but about building a culture of readiness – with training, assigned tasks, including that final critical sweep of a facility by a manager to make sure the investment in safe spaces pays off.

“This can make a huge difference,” Shimon said.

Given the clearcut payoffs in this and other success stories, I asked why these practices remain the exception, not the norm.

Direct experience with disaster seems to be a key spur. Bob Parsons has said his determination to take the extra steps, and incur the extra cost, was the result of early personal experience – in his case a close call with a tornado in June 1973.

Shimon told me he sees this when he and other meteorologists are on the road conducting training seminars. There is a gap in interest between communities that suffered a tornado strike and those that face the same risk but have lucked out so far.

“If a community does get hit, our spotter classes attendance really ramps up” Shimon said.

He said any business owner or homeowner in dangerous regions has to understand they have to take responsibility to recognize the threat is always there - that near misses are no reason to relax.

“We’re investing a lot of Weather Service resources into building a ‘weather-ready’ nation,” he said.

His hope is that the vast tragedy of the latest outbreak can finally jog serious action.

There's work to be done, and I'll do whatever I can to spread the wisdom of people like Ed Shimon, Bob Parsons and Tim Marshall.

But I'll need your help, so please share this story particularly widely.

Read

Catastrophic December tornadoes slam Mid-Mississippi Valley - A great overview of the December 10-11 tornadoes by meteorologist Bob Henson, for Yale Climate Connections

Was Climate Change to Blame for the Tornadoes, or Was It Just Really Bad Weather? - extreme-storm climatologist James A. Elsner in The New York Times

Projected 21st century changes in tornado exposure, risk, and disaster potential - a 2017 paper by Stephen M. Strader, Walker Ashley, Thomas Pingel and Andrew Krmenec that presents a deeply unnerving forecast of tripled tornado impact from a mix of expanded building in danger zones and climate change

The Roanoke F4 Tornado of July 13, 2004 - National Weather Service report on the destruction of Parson Manufacturing

A Survival Plan for America’s Tornado Danger Zone - a 2013 story by me

Watch

An Amazon video of one of its giant fulfillment centers going up in Ottawa, Canada (I'd love to see new ones include tornado safe rooms):

Weather Channel's Storm Stories segment on Parsons Manufacturing riding out the 2004 Roanoke tornado

Support Sustain What

Thanks for commenting below or on Facebook.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues!