Why is this happening? 30 years of climate change reporting summarized in 60 minutes with Chris Hayes

So much of what we discussed in the hot summer of 2018 still holds true.

This is a flashback post, but still as relevant as ever. I’m posting it to provide a bit more context for some folks who are grumpy that I appeared on the Lex Fridman Podcast with Bjorn Lomborg, who’s long been criticized - sometimes legitimately, sometimes not - for pushing “Cool It” arguments that naysayers latch onto as an excuse for inaction moving to clean energy.

In the summer of 2018, Chris Hayes of MSNBC invited me onto his Why is This Happening podcast to explore lessons gleaned in my 30-plus years on the global warming beat.

Much has changed since then in the United States on the climate and clean-energy challenge, with a heap of additional extreme losses in climate-related disasters, but also now hundreds of billions of dollars poised to boost work on climate resilience and energy-system upgrades through the Bipartisan Infrastructure law and Inflation Reduction Act.

But at the global scale, greenhouse gases continue to build in the atmosphere, impacts of climate change mount and the climate treaty process is, as has long been the case, dogged by deep divisions between the world’s established industrial powers and developing countries. COP27 did little to change that.

Here are some excerpts from the transcript but the conversation flows way smoother as audio, so please listen above or on iTunes etc. and let me know your reactions.

CHRIS HAYES, in the intro, describes the super-wickedness of climate change:

[I]f you designed a problem to invade us in all our weak spots, it would be this problem. Like, you can’t see it, is one. You can’t see it, you can’t see the climate problem. You can’t see the climate, you can’t see CO2. Literally, even if CO2 was just a color, or you could see it, we would be dealing with it much more. You see this happen in all these different countries. As soon as they get a certain amount of development and they start getting a ton of smog, they start dealing with the smog. Because it shows up, and people feel it in their lungs, and the stimulus and the response are there, and you see societies start to deal with it.

So you can’t see it. It’s a collective action problem, right? The U.S. could literally zero out all of the carbon that it emits, and that would help a little bit, but we can’t do it alone. If everyone else emits twice as much, then that just gets erased, so everyone’s got to do it together. Collective action problems are really hard, particularly a collective action problem that’s global. Like, we have one atmosphere, and we’ve got 200 countries, all governed in all sorts of crazy ways. It’s also a problem with these crazy long time spans. So, you pump the carbon in the atmosphere for 10, 20, 30 years, and then you got to come up with a way to reduce carbon emissions, maybe even take some of it out of the atmosphere for 10, 20 years. And the results come slowly, the disastrous consequences build up over long periods of time.

…And then on top of that, on top of the ways in which the problem exploits some of our social human weaknesses, the problem is caused by a set of wildly powerful and rich interests, which is the industry that takes the fossil fuel out of the ground and burns is one of the most powerful, wealthy interests in the entire world. There are entire countries they effectively run. They have billions and billions of dollars. The most profitable companies in the U.S. year after year tend to be oil companies, particularly when things are going well for them.

So you’ve got all these ways in which the problem itself already is a confounding and difficult and wicked one, and then on top of that, there’s the political economy of the problem, which is that a small group of massively, massively wealthy and powerful interests are the ones making the money off making the problem worse, and are going to do everything they can to stop us from solving it.

CHRIS asks:

You know, there’s this funny thing about this weather/climate slippage, right? Because obviously, people who are denialists, which again, I actually think is kind of a shrinking rump. Like, I don’t even think it’s a worthwhile group of people to talk about. To me, it’s a shrinking-rump caucus of people. Would you agree with that?

ANDREW REVKIN: Well, I put caution signs around the word “denial” in some ways, because everyone’s in denial on one aspect of the story or another. I’m not going to get into false equivalence arguments about who’s in more denial, and people who are motivated denialists.

I call certain people “stasists,” people who want to maintain the status quo, and who have … Some have a professional interest in maintaining the status quo, you know, lobbyists for oil companies and coal. So that’s one thing, but denial is different. Denial has this sense of, like, it’s partially conscious, you’re in denial.

I’m in denial about the fact that I’m going to die someday, you know? I don’t think about it every day.

CHRIS HAYES: Well, that … I mean, hopefully. I mean, that’s basically my lifelong quest, is to be in denial about that as much as possible. Basically, that’s the recipe for human happiness for me.

If I don’t work enough, and I don’t occupy myself, that reality just creeps into my consciousness, and then I’m bummed out.

ANDREW REVKIN: Yeah. Like, I wrote this piece where I called myself a recovering denialist, because I assumed, the first 20 years of my writing about global warming, like any science writer writing about science, I assumed if I enlighten you, you will then feel the way I do about the thing, and change your practice….

CHRIS HAYES: I’m laughing because that’s such a … It’s such a rational way to think about it, but so untethered from actual reality.

ANDREW REVKIN: Oh my God. Yeah, but it took me 20 years.

CHRIS HAYES: It took you 20 years. You thought, like, “I need to take a pickaxe to this rock of ignorance and just chip away at it, and eventually, I chip away from it, it’ll be clear….”

ANDREW REVKIN pulls out “an artifact” — a copy of his October 1988 Discover Magazine cover story — “Endless Summer: Living With the Greenhouse Effect”:

ANDREW REVKIN describes the closing photo and reads the kicker:

The sun is heading toward the horizon, a farmer in his field is silhouetted, and there’s dust where his boot is hitting his ruined crop. But the kicker, the written kicker on this was … This always haunts me, because it’s like, this is the Groundhog Day aspect of my life. Michael McElroy, he’s still at Harvard, he was at Harvard then, climate guy, he concluded, “If we choose to take on this challenge, it appears that we can slow the rate of change substantially, giving us time to develop mechanisms so that the cost to society and the damage to ecosystems can be minimized. We could alternatively close our eyes, hope for the best, and pay the cost when the bill comes due.” 1988. How many times have you heard a speech since 1988, whether it’s Al Gore or a scientist, saying the same thing?

CHRIS HAYES: So, one of the things that I’ve come around the believing, and it’s maybe a good place to sort of end the discussion, is this is, I think, a weird thing to admit because I think it cuts against what my kind of first principles are as a person and as a citizen and as a thinker, which is that climate change is a political problem. It will be solved through political action and collective action. We have come together to solve very hard problems as a political matter before. Sometimes it’s really brutal. Sometimes it’s extremely conflict-laden. In some cases, as in the problem of slavery, it costs the lives of 600,000 Americans who fought the bloodiest war in the country’s history over it.

ANDREW REVKIN: Damn.

CHRIS HAYES: But fundamentally, political problem fundamentally will be solved through politics and collective action. I think I don’t think that anymore. I think what I think is that there’s gonna have to just be a technological solution, that basically just because of the wickedness of the problem, that the engineer … We just need some engineers to just figure it out in a variety of complex ways, which is like making really good and very cheap and scalable renewable energy, changing grids, coming up with ways to take the carbon out of the atmosphere. That’s basically where my hope is now, which is by no means advocating quietism or end of political action, but that avoiding real, real disaster is gonna involve a very health chunk of brilliant engineers figuring some crazy shit out.

ANDREW REVKIN: Not just engineers, but social and behavioral science has to be part of this in terms … I don’t mean … It used to be to do that, to sell concern, that’s the big fail, and that’s a big fail of a lot of journalism, too, bigger headlines, scary stuff.

CHRIS HAYES: Right, right.

ANDREW REVKIN: It’s to look at how do you foster conversations. Part of my … I’m in National Geographic Society now. That’s the grant-making part, and I’ve been writing a lot lately about how do you find consensus amid all the polarization, and you can have consensus on vulnerability reduction, absolutely. Libertarians hate the idea of subsidized flood insurance. So, that’s an area of innovation that’s just as important, I think, as a better battery, because if you can find a way to get Libertarians and Liberals for very different reasons to focus on one of the vulnerability issues related to climate change, you’re doing something very powerful.

I wrote this piece in National Geographic Magazine in July that’s like an essay looking back at 30 years of learning and unlearning, and as you said, I went through this … I thought it was political. I thought it was diplomatic. I thought it was technological. I thought it was all these things, and I realized, no, it’s not that, it’s not that, and then I realized it’s partially all of those things. It’s this emergent phenomenon of a species, and I wrote this 10 years ago. I call it Puberty on the Scale of a Planet.

Here we are. We’re in zoom mode. Fossil fuels were the zoom part in a revving up car. When I was a teenage, a friend of mine took me out in his hopped up car. We got up to 125 miles an hour on an un-built stretch of highway, and I thought, wow. So, that’s been us so far, and there are these signals, which are really like growing up, that transition from puberty to whatever comes next. When you face that kind of transition, the other thing about this issue that seems vital, but maybe it’s the hardest thing of all, it’s response diversity.

Response diversity is necessary when you have a complicated problem. I stumbled on this after a fight with David Roberts during the keystone fight. We had different positions on what to do, and I started googling around for environment response diversity. It was like, can’t we all get along kind of thing, but we all want to solve this climate issue, but Jim Hansen is pro-nuclear. Bill McKibben is pro-renewables. They found a way to tie themselves to the same fences at the White House and not argue with each other about their visions of the solution, but most of the community around this issue hasn’t figured that out yet.

So, one of the challenges, and I don’t know the answer to this question, it is like a communication or social frontier. Response diversity is key. Some country’s, China’s gonna pursue nuclear if we don’t. It’s in the mix. My wife and I disagree about nuclear. We live eight miles from Indian Point, but we love each other. So, how can we have a conversation? How can we build policy where if you’re dug in on policy A and the other person who wants to solve the climate problem is dug in on policy C, how can you acknowledge each other’s positions and still pursue … Acknowledge diversity and still pursue progress, and that’s like … I don’t know. I don’t know how that happens.

CHRIS HAYES: I mean, it’s funny because it ends up being this situation, which you kind of walk all the way through these different domains of knowledge where it’s like first you’re in physics, and then you’re in international relations, and then you’re in political theory, and then you’re in cultural cognition, you’re in social theory, and then you end up in this sort of … It almost feels like you end up in this kind of … I don’t want to say spiritual place, but a place of collective consciousness and an existential question about what the human species is.

ANDREW REVKIN: Oh, yeah.

CHRIS HAYES: I mean, it’s an existential test about what the human species is and what the human species is capable of. That’s what we face.

ANDREW REVKIN: You’ve led to one of my other big insights, which came as a science writer for 30-whatever years, and in 2014 I went to the Vatican to a big meeting called Sustainable Humanity, Sustainable Planet: Our Responsibility, and it was the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. I got to spend a week there. I was the rapporteur, the respondent or whatever, and I was surrounded by geniuses. So, I turned to Walter Munk, this unbelievable oceanographer from Scripps after dinner and wine, and I said, “So, Walter, what do you think is gonna get us through this century,” and here he is at 96, and he’s a physical oceanographer, not even a cool fish guy. He’s all about numbers. He turned to me and he said, “It’ll take a miracle of love and unselfishness,” and that … I mean, my hair almost prickled.

Literally, I was scribbling, and I’ve had more than, I’d say, half a dozen conversations with people who really understand this issue in the most profound way, and they all end up saying, “I don’t know,” but they’re working on it anyway, and that’s this weird thing because everyone has a position you’ve staked around knowledge. It’s all greenhouse gases and gigatons and megawatts, and sort of acknowledging that we don’t know is, I think, important. Not just because of the uncertainty, but it’s just a fundamental reality of this thing we’re gonna get through. I think, I believe … Those words get all mixed up. I wake up in the morning kind of optimistic, and I usually go to bed kind of sapped, but I wake up in the morning optimistic and go to bed sapped and keep moving on.

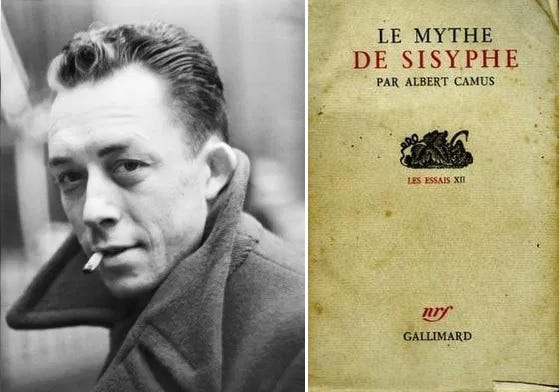

CHRIS HAYES: You know, my favorite piece of writing is Camus’ Myth of Sisyphus, which is about an eternal pointless struggle. Right? Sisyphus wakes up every day. He rolls the rock up the hill. It rolls back down, and the point of the essay, which is a kind of real touchstone for me in how I think about life and whatever kind of personal theology I have, or sort of anti-theology, I think Camus is an atheist, is that it’s the process, not the … There’s something … You put faith in the process of the joy of the task or the struggle of the rolling of the rock, and the last line of the essay is, “One imagines Sisyphus happy,” and that’s the way I think I think about this wicked problem.

I love this stuff. As a tour guide in central Australia I have to tell my guests that they will not be seeing kangaroos and emu because technology was used to introduce horses and camels. Both introduced species have destroyed the food source of the native animals. Latest tech I heard was that to deal with the feral cat problem another predator needs to be introduced so the cats have a rival.

Tech has created the current climate change problems through manufacturing and capitalism. The constant fear based propaganda of scientists of all kinds. Consumption of natural resources has created the problem so the best answer is to manufacture something else. Do we know the long term effects of Lithium mining? Do we know the effects of waste created from renewables. To me the tech based solution is just introducing another predator to the natural world. Living within the natural world is the solution not creating more synthetics. The Indigenous Australians have survived for 40,000 years in a sustainable way. Maybe it is the Indigenous culture of the world that have the answer to our problems. It is certainly not technology.

Excellent program! Both thought provoking, insightful, and, in some sense, hopeful. That said the elephant in the room that was seldom mentioned is that the real driver of the climate problem is ever increasing numbers of humans, being. Who knew that Chris Hayes was so intelligent and so well informed about this very complex topic? And yet like so many others today rather than acknowledging the perils of consumer driven, over population propelled, growth for growth sake he continues to base his reason for hope upon the very technology that has created these overwhelming problems in the first place. Hate to be the bearer of bad news but technology tends to create problems faster than solutions! In his excellent book, "Why Things Bite Back" author Edward Tenner details the many promises used to promote various technologies and then analyzes in detail how those same technologies have led to even more difficult to solve problems. Modern man's addiction to technology began when he first picked up a rock and used it to smash a walnut he wanted to eat. But all these thousands of years later that addiction to "tool solutions" is threatening our continued existence as a species. Clever tools and techniques may well allow us to stumble deeper and deeper into the extinction trap through allowing more and more humans to survive. But as the number of humans continues to increase and over burden the planet's ability to sustain those numbers we will finally have to recognize that as Thoreau warned many years ago that "we have become the tool of our tools!"