I hope you’re already following ’s Substack effort to delineate what he calls “The Work” of building an energy and resource future that also mitigates the global heating challenge. If not, below I’m adding a snippet from his valuable new post building on the “Watchwords” conversation I did pre-election with Mekala Krishnan, the lead author of a recent McKinsey Global Institute report, “The hard stuff: Navigating the physical realities of the energy transition.”

His post describes three ways to manage a tough part of what I call the climate “scale monster” - emissions from existing or planned fossil-based energy systems that are - because of economic, political and technical factors - “locked in” to the human enterprise for years or even decades to come. His definition:

“Lock in” is shorthand for complex market phenomena. Once pipelines, export terminals, and power plants are built, they will remain in use. The investors who committed capital want to recover their money and the jobs in these facilities want stability. Ongoing operations means more [greenhouse gas] emissions, both from direct hydrocarbon use and upstream leaks (these are extra bad for climate). Emissions will add to atmospheric stocks, compounding global warming. Absent early retirement (in itself an expensive proposition), the plants will operate and emit.

He focuses on three solutions - carbon capture and very long-term storage, designing systems for new post-carbon purposes, and making sure they can scale back through policy choices.

Carbon capture is much debated, with climate activists focusing on it as moral hazard (distracting from the core need to cut warming pollution) or a greenwash path for industry and some global development analysts like Vaclav Smil deeply dismissive of its capacity ever to work at the gigaton scale of the global warming challenge (watch Smil do the math in this 2009 onstage conversation we had).

But I’m with Friedmann and others who see it as one vital tool in the decades ahead. The climate challenge is all about YES AND. An important task is discriminating between greenwash - which is real - and legitimate research and deployment policy and practice. Here’s a 2022 Department of Energy report.

Friedmann has moved from climate and energy research into the business of carbon abatment but remains a trusted guide for me. He is transparent about where and how this technology makes sense and what it can’t do.

CCS realities and questions

Here’s a conversation I had with him one year ago laying out the landscape (you can also watch and share it on YouTube):

Here’s an excerpt from his post but please click the link to read the full piece and subscribe:

Lock in is a choice, not fate

Infrastructure & investment can counter emissions inevitability

The forces that lead to “lock in” are real. Governments want the energy, the jobs, the tax base. Communities want them too. Investors want their money back. Shuttering infrastructure early is expensive – so is replacement with new infrastructure. In reality, the key stakeholders aren’t comparing options based on marginal or levelized costs – they’re comparing tear-down costs.

Does this mean we’re doomed? Roll the credits?

No. It does not.

“Lock in” is a choice. Existing fossil fuel infrastructure, whether pipelines or power plants, also can be retrofit, repurposed, and reimagined.

First choice: manage carbon emissions

You want to limit emissions from fossil fuel plants? Here’s an idea – limit the emissions.

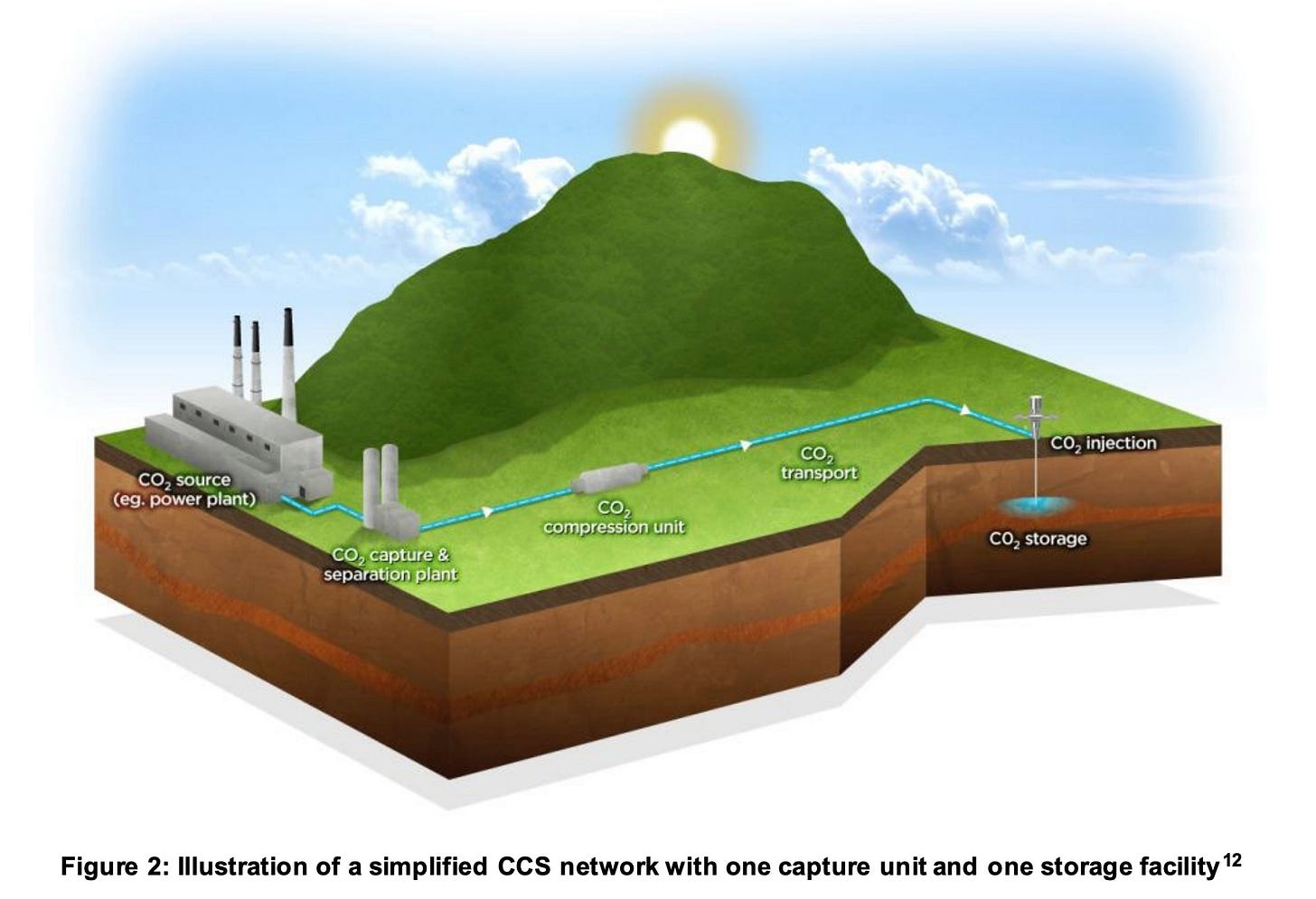

Continuing emissions from fossil fuel facilities is a choice. We have the technology to capture the emissions and keep them out of the air and oceans indefinitely. Carbon capture is well established technology, operating for nearly 30 years in Norway and the US, working today in 16 countries capturing >50 million tons of CO2 each year. Over 600 projects are in design and commissioning, with >230 project added in 2023.

YES, it costs money to stop emissions this way. Clean ain’t free.

However, in most markets capture is a cheaper option than premature shut-down or repowering with renewables or nuclear. Durable policy in the US and Europe supports the deployment of carbon capture retrofits, so existing steel, chemical, fertilizer, and power facilities emit less. Even without incentives, the cost of abatement using carbon capture is cheaper than many options in most economies – including repowering with renewables.

For maximal climate benefit, the captured CO2 should be locked up indefinitely, stored for hundreds, thousands, even millions of years

Punchline no. 1: If you’re pro climate action, you should be pro CO2 pipeline, so they can take captured CO2 to dedicated facilities that. There’s already 5000 miles of CO2 pipeline in the US (compared to 3 million miles of natural gas pipelines). Without the pipelines, more expensive choices could do the same job, requiring more road, rail, and barge traffic.

Second choice: repurpose what you have.

LNG export terminals will be built. Period.

Can they be repurposed? Yes.

Specifically, they can be converted into ammonia export terminals for about 11-25% of the original cost. Ammonia is the main ingredient in fertilizer and can itself be a clean fuel. In the future, we can choose to convert LNG terminals to export other things – the opposite of lock in.

Already some existing natural gas pipelines have been converted to transport CO2. Some fossil export terminals can be converted to receive CO2 from other nations, creating new trade and commerce.

Third choice: reduce use before shuttering.

One can use existing facilities less.

When we succeed in the future at accelerating the deployment of clean energy and fuels, these can displace capacity in existing plants. This has happening in some advanced economies – a combination of mandates and incentives help deploy renewables and reducing the use of fossil fuels in existing facilities.

This must be accelerated, and someday will be. That’s a choice as well.

One last thing. Friedmann is a fine musician and once composed a climate melody reflecting global temperature since 1400. He joined many of my Sustain What Sunday Sanity webcasts during the pandemic.

Flashback

I covered carbon capture on Dot Earth back when it was called “clean coal” in climate context - a very dubious notion, yet promoted during the Obama administration as well as back in George W. Bush’s time in the White House. Here’s a look back, including a remarkable scene at the Democratic National Convention in 2008 (and this group was also at the Republican Convention that year).

Dang! My only regret is not following Andy years ago. He consistently tells the truth and uncovers the whole climate change fiasco. He deserves to close ala Cronkite in all his lucid posts.. "And, that's the way it is".

I agree ver much with what you say about lock in and CO2 capture and sequestration. (You mention only sequestration of CO2 as gas, not reacting it to create inert compounds, nor capture from the atmosphere but those are also an option).

You do not discuss what kind of incentives would lead firms to capture and sequester CO2. It is worth pointing out that regardless of its present political unpopularity, taxation of net emissions is the way to incentivize the lowest cost technologies. To be one step more specific, there could be an excise tax on the first sale of a carbon-containing fuel in proportion to its carbon content and a standing tax credit (at the equivalent rate) for atmospheric capture and sequestration.

This is far from denigrating discussion and promotion of other more immediately politically feasible incentive options, but they too need to be designed to incentivize low-cost reduction of emissions. Conceptually, other policies should seek to mimic the effects of the tax on net emissions.

These considerations should also rule out measures that reduce emissions by very small amounts at high cost. I have in mind certain numbers I have heard mentions of programs within the IRA as well as regulatory measures that block production and transportation of fossil fuels in the US. If successful, these measures will only result in production elsewhere with minimal reduction in global emissions, but the opportunity cost will be borne by the US.

https://thomaslhutcheson.substack.com/p/power-decarbonization-and-lng-exports

https://thomaslhutcheson.substack.com/p/why-not-lng-exports

One important way in which other incentives should mimic the tax is to be at least fiscally neutral on the margin. It is not sustainable to offer incentives that have fiscal costs if the net effect of paying out those incentives is to increase borrowing. Fiscal borrowing for CO2 emissions reducing incentives mainly crowds out other investment and so would make dealing with climate change a drag on growth.