Gauging Losses and Lessons in Turkey's Unfolding Earthquake Calamity

Along with my climate reporting, I've also long been on the "rubble in waiting" beat and am haunted now by earthquake vulnerabilities I saw in Istanbul in 2009.

Consider donating to key disaster relief organizations. Rescue, response and recovery will take years, and this is a region already straining under the weight of supporting millions of Syrian refugeees. Global Citizen has a fine list.

UPDATE, Feb. 15, 3 pm ET - The chilling map below shows the explosive growth of housing in one of the cities in the heart of the impact zone from Turkey’s latest severe earthquakes. The lack of earthquake resistance reflected in the destruction was no accident, according to a burst of revelations in recent days showing that zoning amnesties were granted by the thousands under the adminstration of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in recent years, aimed at accelerating construction to keep up with population growth.

INSERT, Feb. 11, 11:30 a.m. ET - To understand more about why thousands of buildings fell, and why others didn’t, in the devastating earthquakes that struck Turkey and Syria, please listen to veteran earthquake-safety engineer Kit Miyamoto, whom I interviewed on February 10, just after he arrived in Adana, Turkey, to help assess needs as agencies and nongovernmental organizations sift wreckage.

Original post - Here are some wider implications and ideas to weigh as the awful news continues to emerge from the world’s latest great seismic jolt: the 7.8-magnitude major earthquake (and a 7.5-magnitude aftershock and dozens more) that shattered hundreds of cities, towns and villages and has taken thousands of lives across southeastern Turkey and over the border in Syria.

Social media and news reports are filled with absolutely chilling and horrific video showing countless buildings collapsing and all-too-familiar images of frantic searches for trapped relatives and colleagues.

Tough reality - there’s no surprise here

This toll was absolutely to be expected. This region at the intersection of Europe and Asia is rife with dangerous faults.

But even worse, this part of Turkey has in recent years accommodated millions of refugees from Syria, ballooning the potential popualtion at risk. A 2018 paper that I tweeted about last night projected how this flow of dislocated people could swell urban losses.

The research, first described at a 2016 meeting of the American Geophysical Union, showed that the vast majority of refugees are not in tents. For the key point, read this LiveScience report citing Bradley Wilson, who was at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville at the time and is now an associate professor and director of the Center for Resilient Communities at West Virginia University:

It turned out that just 14 percent of the refugees lived in traditional tents or container refugee camps in Turkey, said Wilson…. "A majority of the refugee population is not located in refugee camps and is distributed amongst the local cities and villages."

And it is those cities and villages that have been absolutely hammered.

Here’s the latest map of Turkey’s population of around 4 million registered refugees (nearly all from Syria) - the world’s largest for the eighth year in a row. Compre those high-density provinces to the earthquake map above.

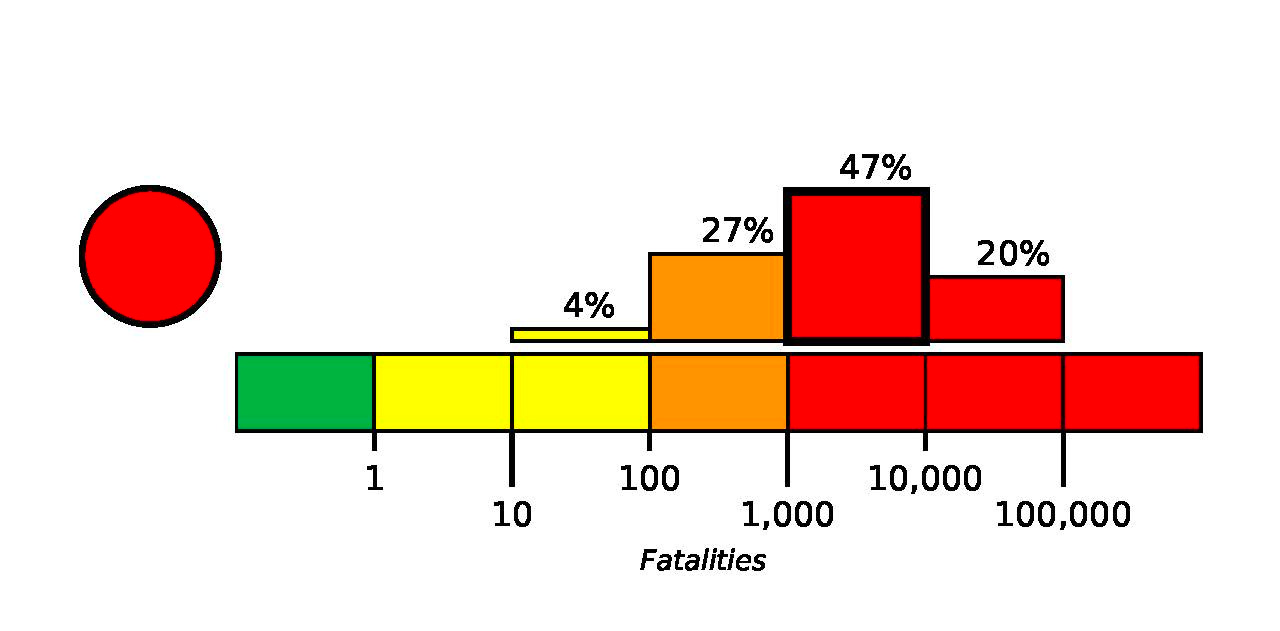

Death tolls will rise well beyond the initial esimates. The U.S. Geological Survey’s PAGER model (Prompt Assessment of Global Earthquakes for Response) projected the initial major 7.8-magnitude shock in the red zone with up to 10,000 deaths conservatively estimated. This model assesses earthquake intensity along with population density and other factors to help guide rescue and recovery efforts. I first wrote about it after the 2014 Nepal quake.)

It’s mostly* buildings, not shaking, that kills

Pause for a second to ponder what you’ve seen on TV or news websites.

As earthquake engineers stress, most of the time*, buildings kill people, not the shaking itself.

I first reported on this reality from Istanbul, Turkey, in a 2009 front-page story for The New York Times on megacities facing megarisk from impending great earthquakes. I spent a day exploring poor and middle class neighborhoods in the sprawling metropolis with Mustafa Elvan Cantekin, who at the time directed a Neighborhood Disaster Support Project funded by a Swiss development agency. Here’s a snippet from the longer video report I did for The Times:

Over and over Cantekin would point to buildings with “soft floors” - ground-level retail spaces with very little reinforcement supporting far heavier residential floors above, or buildings where, for tax purposes, higher floors jutted out beyond the dimentions of the ground floor, or homes where floors were added as families expanded.

He and some other earthquake engineers I’ve interviewed over the years call such structures “rubble in waiting.”

INSERT, Feb. 8 - More on the danger of “soft floors”

This 2008 paper by Bangladeshi engineers Sharany Haque and Khan Mahmud Amanat explored the physics of “soft floor” failures in earthquakes and included some vivid imagery: “Seismic Vulnerability of Columns of RC Framed Buildings with Soft Ground Floor” [RC = reinforced concrete]

~ End Insert ~

Sadly, video of many of the deadly collapses in southeastern Turkey shows buildings just like the ones we toured. Here are some still images from an Instagram post of a building collapse showing the “soft floor” collapse.

Read this stunning 2021 post on The Conversation by a New Zealand environmental sciences professor, Ann L. Brower, who was the only survivor out of 13 people in a bus crushed by components of a building that collapsed in the 2011 Christchurch quake.

Her personal advocacy led to what New Zealand officials ended up calling the “Brower Amendment” to the country’s earthquake buildling rules.

Mind the disaster gaps

There’s an enduring worldwide challenge facing communities that have expanded over many decades into zones facing extreme, but sporadic, threats like major earthquakes, resulting tsunamis, big volcanic eruptions or - for climate - megadroughts or the most extreme atmospheric river floods.

It’s exceedingly hard to unbuild, move back, or retrofit at scale.

Another issue? Much of the vulnerable exposure to the biggest earthquakes was built in a great-earthquake hiatus in the seond half of the 20th century.

Roger Bilham of the University of Colorado, one of the world's top seismologists, has long worried about a dangerous gap in global experience with great earthquakes. After the 2011 Honshu earthquake and tsunami devastated Japan, Bilham produced a graphic showing the 40-year great-quake gap - from the 9.2-magnitude Alaska quake in 1964 to the great Sumatran quake and Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004. [I alluded to this in a post last year on megadroughts, which present a similar challenge.]

Note that the great-quake gap came just as the "great acceleration" of human population and development was getting into high gear.

I’ll be adding more insights and ideasa here as time allows. Please post comments with links to what you’re seeing.

Reading and resources

Roger Pielke Jr. filed an interesting post this morning offering a wide view of trends in major earthquakes and losses:

The potency of the back-to-back major earthquakes in eastern Turkey was demonstrated in the loss of ancient structures that have withstood countless past temblors. One example:

I encourage you to click back to a 2010 interview I did with Ali Ağaoğlu, a billionaire developer in Turkey who caused a stir in 2009 when he admitted that his family’s company — and most other developers — routinely used inappropriate materials during a building boom in Istanbul in recent decades, creating enormous vulnerability because of the long history of powerful earthquakes in the sprawling city.

Here’s one tidbit:

Andy Revkin - For several years now I’ve been trying to understand ways to reduce vulnerabilities to earthquakes in big cities in developing countries, including Istanbul. Last year, in an interview with a Turkish newspaper, you spelled out clearly that it was normal, when many buildings were erected, to use materials that you would not use now. That’s a difficult position to be in.

Ali Ağaoğlu - I am ‘coming from the kitchen’ in this business, as we say, meaning all my family, under my father, were also a part of this sector, the construction sector. I grew up working with him, witnessing all of the development at that time. I’m not in a position to regret what I’ve said. The fact is that 70 percent of all the settlements in Istanbul, I would say, are vulnerable to a major earthquake. This is a diagnosis. Without the proper diagnosis treating a patient is not possible. The construction materials used for various settlements in different parts of Istanbul used to be of poor quality.

Postscript *

At the asterisks above, I updated the post to note that buildings are the fatal element in earthquakes most, but definitely not all, of the time. The earthquake scientist Mark Quigley stressed this in a comment he emailed along with a link to a fresh piece he wrote for The Conversation explaining that horrific pancaking phenomenon seem in all too many of the videos of collapsing buildings.

Here’s what Quigley, whose expertise I’ve drawn on before, said about buildings and other lethal elements in earthquakes:

it is the confluence of an imposed hazard (shaking) with exposed and vulnerable infrastructure that often amplifies loss of life (and sometimes things like ground failure, etc cause building damage and loss of life, even in buildings designed in excess of code), and

plenty of people die in earthquakes from other hazards that do not relate to buildings, but can be attributed to strong shaking – for example earthquake-triggered landslides (e.g., in 2008 Sichuan earthquake, estimated geohazards (landslides) responsible for at least one third of the death toll, i.e., >20K fatalities….)