How a Two-Century Megadrought Gap Set the West up for its Water and Climate Crisis

A new study further cements how global warming, by drying soils, is raising odds of megadrought conditions across a water-dependent swath of the western United States

Please SUBSCRIBE to receive my posts by email.

Since the turn of the 21st century, researchers probing evidence locked in tree rings and other clues to past climate conditions have been building an increasingly unnerving picture of southwestern North America as prone to deep, prolonged droughts.

Megadrought is the emerging term for the worst of these extreme dry spells - those lasting two decades or more. What these scientists couldn't have known until recently (that's how long droughts work) is that while they were studying the drought history of this region, the area was sliding into a potent new megadrought - and a unique one because it wouldn't exist without the growing boost from human-driven global warming.

Read the paper and full caption

A paper published on Monday in Nature Climate Change appropriately got a lot of news coverage for advancing understanding three ways:

The researchers said the off-the-charts extreme dryness of 2020 and 2021 made this the worst megadrought in the region in at least 1,200 years.

They found a firm signature of human-driven global warming, accounting for more than 40 percent of the severity of soil dryness. "In fact, without [human-driven climate change], 2000–2021 would not even be classified as a single extended drought event," the authors wrote. (In the art above, figure b shows the differential depth of the drought with the amped-up greenhouse effect compared to what models projected if it was excluded.)

They said it was likely that more years of extreme dryness and all that comes with it are still ahead before the drought breaks - as all droughts do. The lead author, A. Park Williams of the University of California, Los Angeles, stressed that climate change is not stopping: “Climate change is changing the baseline conditions toward a gradually drier state in the West and that means the worst-case scenario keeps getting worse.”

As you've seen if you tracked news coverage last summer of the unprecedented low reservoir levels behind the Hoover and Glen Canyon dams along the Colorado River, the West is finally recognizing that it faces a sustained and intensifying water crisis.

The crisis is driven only partly by the mix of natural climate variability and human-caused global warming. Decades of water-dependent population growth and economic development have created the classic "expanding bull's eye" pattern that turns a natural hazard (in this case exacerbated by greenhouse gases) into an unnatural disaster.

Water resources have literally vanished from maps - as with Tulare Lake, which in the 1800s was the largest freshwater body west of the Mississippi but vanished as incoming rivers were diverted for farming and urban water supplies. This 1898 spread in the San Francisco Call says much:

There's an enormous amount of great reporting on the policy challenges this situation has created. I particularly recommend a recent three-part Buzzfeed News series on the West's water crisis written and photographed by Caitlin Ochs, particularly the story titled "People — Not Just The Megadrought — Are Driving The West’s Water Crisis."

The megadrought gap

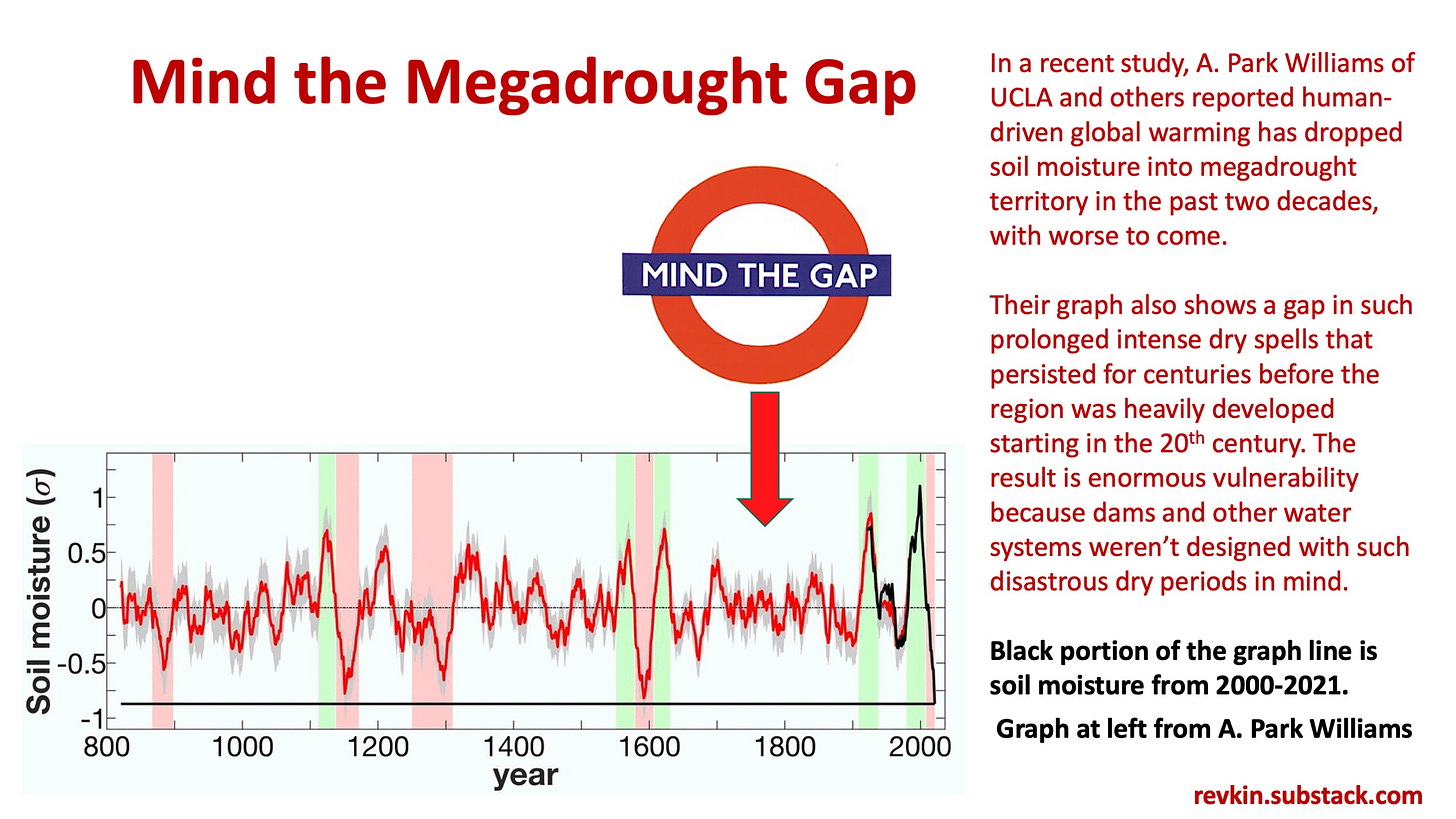

At the grandest time scale, there's another reason the West finds itself in such a profound hydrological predicament: a protracted megadrought gap. While tree rings show a series of megadroughts since the year 800 (those vertical pink bands in the graph at the top of this post and below), have a look at the yawning blank zone from roughly 1700 until 1900.

Here's a closeup view with a "mind the gap" symbol marking the spot.

That was also a span when the colonial presence into the West was in its earliest stages. But if there had been a megadrought, there almost surely would have been some history, including through Indigenous history, to weigh as the 20th century dawned and plans were drawn up for the future of water.

That, of course, didn't happen.

In a phone interview, Williams at UCLA expressed the situation this way: "The one thing that we were suckered by is the fact that there wasn't a naturally occurring megadrought during the 1800s or 1900s. And so the backstops that we built to safeguard against the worst droughts weren't actually built to be able to withstand the worst droughts."

Back in 2014, another scientist deeply dug in on the West's water history, Lynn Ingram of Berkeley, gave a talk laying out her findings, including this line: “The past 150 years have been wetter than the past 2,000 years.... And this is when our water development, population growth and agricultural industry were established.”

Watch her here:

"Shock to trance" water policy

I first got to know Ingram through her work on another California extreme - atmospheric rivers that can produce "megafloods" every century or two, including one that turned the Central Valley into a freshwater inland sea from December 1861 through the following January. I featured a short essay on this disaster by Ingram in the illustrated book of 100 weather and climate "moments I wrote with my spouse in 2018.

The megadrought-megaflood flipflop climate reality is another confounding factor bedeviling drought-resilient planning in the West. It's hard to craft enduring water policy facing whiplash patterns, on long and short time scales, between dry periods and what are called "pluvials" - wet stretches.

I'm all for exciting measures like adding sun-shading solar panels to limit evaporation from the vast canal systems of the Central Valley and bringing water to Southern California. But they're nowhere near the scale of the challenge.

A state-funded $20-million pilot project will cover 1.5 miles of California water canals with solar panels to evaporation and greenhouse-gas emissions. (Turlock Irrigation District)

While at The New York Times, I wrote a couple of pieces musing on whether California can avoid a "shock to trance" approach to water policy, mirroring the woeful pattern the United States has shown on energy policy. (I first heard that "shock to trance" phrase used in 2008 by President Barack Obama in the context of high gasoline prices.)

Here's hoping.

Mind the other disaster gaps

By the way, that "mind the gap" issue is all around - not just in water and climate policy. As I wrote a decade ago, Roger Bilham of the University of Colorado, one of the world's top seismologists, has long worried about a dangerous gap in global experience with great earthquakes. After the 2011 Honshu earthquake and tsunami devastated Japan, Bilham produced a graphic showing the 40-year great-quake gap - from the 9.2-magnitude Alaska quake in 1964 to the great Sumatran quake and Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004.

Note that the gap came just as the "great acceleration" of human population and development was getting into high gear.

Resource

Here's the current view on the North American Drought Monitor:

Help build Sustain What

Any new column needs the help of existing readers. Tell friends what I'm up to by sending an email here or forwarding this introductory post.

Thanks for commenting below or on Facebook.

Subscribe here free of charge if you haven't already.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues.