California's Atmospheric River Blitz is a Mild Reminder of an Inevitable Climatic Calamity

With or without global warming (and warming will likely worsen things) the state has built extreme vulnerability to rare, but inevitable meteorological monstrosities

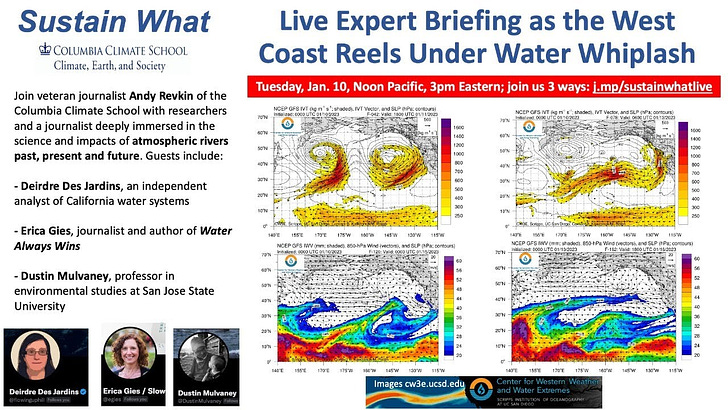

For the latest on California’s whiplash water crisiss watch this Sustain What webcast with some fantastic on-scene experts:

UPDATES added as California flood emergencies play out:

Jan. 10, 1 pm ET - The earth-moving power of torrential rain in California’s landscapes is on vivid display here via Fresno California Highway Patrol footage:

Jan. 9, 6:15 pm ET - Rob Calmark, an ABC TV meteorologist in northern California, posted a sobering thread on Twitter today with this key takehome line: “[T]his is a historic cycle of storms...straight up. We rarely see this many consistent strong Atmospheric River style storms. We are in one now...with more to come...for the next 10-15 days.”

Jan. 9, 5 pm ET - Much of Santa Barbara County, particularly areas prone to mudslides when extreme rain follows wildfires, is in crisis mode.

Jan. 9, 3:30 pm ET - This tweet links to sobering video from Dustin Mulvaney, a professor in environmental studies at San Jose State University, and a must-read op-ed in The New York Times on how California could store some of the water in these flooding events for dry times, written by Erica Gies, author of “Water Always Wins”:

Original post January 4- As another potent West Coast atmospheric river makes landfall and headlines, it’s worth restating that Californianas are not remotely ready for the worst that the region’s whiplash climate can throw at them.

The spate of January atmospheric river events is a shadow of what’s possible - actually inevitable.

For the latest warnings on this week’s hurricane-force system, track relevant National Weather Service output and follow extreme-weather scientists like Daniel Swain (@weather_west). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has an invaluable Atmospheric River forecast site, as well.

I’ll add notable updates here.

Atmospheric river basics

The term “atmospheric river” first appeared in the research literature in 1998 but these phenomena are a normal part of weather systems over many oceanic regions.

According to a comprehensive 2013 report, these sytems are responsible for 90 percent of global water transfer by the atmosphere! Even as most headlines portray these systems and threats, for places like California they are also a vital factor breaking droughts and restoring snowpack.

The climate change question

Every time a major system hits, you see a spate of news items on the role of climate change. There’s no evidence of a global warming impact yet, but climate models do project intensification of atmospheric river rains as warming continues. Here’s an open-access 2022 Science Advances study by Xingying Huang and Daniel Swain: “Climate change is increasing the risk of a California megaflood.”

Another 2022 study, by a team led by Christine Shields of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, went so far as to analyze how solar geoengineering - injecting sun-blocking aerosols in the stratosphere - might affect future atmospheric rivers in a greenhouse-heated world. The authors reported finding that “geoengineering results in fewer extreme rainfall events and more moderate ones.”

Such research is important, but debates over climate change can distract from the core reality - which is that past patterns of these extreme events coupled with societal expansion in flood-prone regions guarantee momentous impacts.

Megafloods past and future

Even California’s mind-boggling megaflood in the winter of 1861-2, which turned the Central Valley into a freshwater sea, pales beside what the U.S. Geological Survey has said research on past rain events has found:

“The geologic record shows 6 megastorms more severe than 1861-1862 in California in the last 1800 years, and there is no reason to believe similar events won't occur again.”

More than a decade ago a batch of agencies and university scientists ran a scenario, called ARkStorm, that described the scope of potential losses when (not if) an event approaching the magnitude of the 1861-62 calamity unfolds.

Even with that scenario and subsequent efforts to prepare the state, I’m actually not sure it’s possible to be fully ready given the vulnerability that’s been built in the last 100 years in floodable regions - that familiar #expandingbullseye pattern - and the science that’s emerged in recent decades showing just how profoundly extreme both megafloods and megadroughts can be.

When my wife and I wrote our 2018 book, Weather, an Illustrated History, the mini chapter on that megaflood and its implications for California today and tomorrow was contributed by Lynn Ingram, a now-emerita University of California, Berkeley, scientist who’s spent decades uncovering unnerving evidence through more than 2,000 years of past extreme drought and flooding.

Inserted tweet, Jan. 9 - Michael Dettinger - a collaborator with Ingram and a hydroclimatologist studying extreme climate events for decades - posted this summary of sedimentary evidence of past California megafloods:

In a 2017 interview with Josh Chamot of Climate Nexus, Ingram laid out the stark reality of past extreme climatological norms that weren’t evident when California had its modern expansion in the 20th century:

If you go back in time during warmer periods, such as the Medieval warm period, there was drought in California — on average 30 percent drier for more than a century. Within those droughts were megafloods. So even in the midst of a drought, the weather can be punctuated by these really big storms.

There’s that climate whiplash effect. Then she described another factor amplifying risk from the next deluges, beyond the expanding bull’s eye of growth in danger zones - the dramatic human-caused subsidence of crowding landscapes:

As the climate warms, I’m definitely concerned about what might come next. California has been growing in places, like the Central Valley and the Delta. Parts of the Delta are below sea level because it has been sinking. The Central Valley has also been sinking because of groundwater pumping, and some parts are 30 feet deeper than in 1861. It’s so much worse now — there are more than 6 million people living in the Central Valley alone.

That’s worth repeating. Some parts of the Central Valley are 30 feet deeper than in 1861.

Resources and reading

Six Facts You Should Know About Atmospheric Rivers, a nicely written and illustrated guide by the U.S. Geological Survey.

The Coming California Megastorm, a vivid New York Times multimedia report by Raymond Zhong and Mira Rojanasakul

Help support and build Sustain What

I’ve been on Substack now for several months and am thrilled to report I’ve added more than a thousand subscribers since leaving Bulletin. But I sense this conversation we’re having deserves wider circulation. So please share this post and encourage others pursuing progress on this turbulent planet to subscribe.

And do chip in financially if you are able to do so - to help keep most content open to those who can’t, and to help me get some help with copy editing and the like.

Parting shot

In Maine we don’t get atmospheric rivers, but we do get some wild weather. If you missed my social media flow when the transcontinental polar vortex drew storm-force winds onshore, here’s what that did to the dock at the home we moved to last June.

The weight of humanity on California's sliding and sinking landscape. My sister's family being evacuated from their home in the Santa Barbara area in the 2017 Thomas fire burn scar. That is where all the mudslides in Montecito occurred in early 2018.

We don't need to worry about any of this because there is a solution. The Yellowstone Super Volcano. Once the Yellowstone volcano goes off so much ash will fall on California that it will raise the ground level sufficiently to prevent serious flooding. I knew you'd want to know this good news right away. :-).