As the Human Population Tops 8 Billion, a Look Beyond Bomb📈 and Crash 📉 Panic Proclamations

After a two-century spike, huge demographic shifts are under way. Pay less attention to debates about explosions and collapse, and more to fostering girls' rights and mobility.

In a great post-election dispatch James Fallows pushed for political media to cut back on “expert” predictions given how normal it is to be wrong:

No one knows what is going to happen. Least of all — it seems — the political “experts.” So let’s waste less time pretending to know, and invest more in looking into, sharing, and learning from what is actually going on.

I would propose this same practice be adopted by journalists and the rest of us pondering what to think and do about population trends. In this case, invest way more in looking at what can be done today to improve the lives of girls and people on the move and less on portentous predictions.

There’s no time like the present, given that this week marks the final push in the COP-27 climate negotiations continuing in Egypt, the start of the 2022 International Conference on Family Planning in Thailand - and given that November 15 is the day the United Nations chose to mark humanity crossing the 8 billion population threshold.

Loud edgy arguments about what may happen when, and after, human numbers and resource appetites crest too often obscure the vital actions or investments communities, governments or other institutions can pursue now, on the ground, to foster the capacities and conditions that can cut odds of worst-case outcomes.

To draw attention to under-appreciated opportunities, I hosted a spirited, action-oriented Columbia Climate School Sustain What conversation on Humanity Beyond 8 Billion and hope you’ll take time to watch, listen as a podcast or skim the rough transcript on Trint.

You can also watch and share on LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook.

Two core themes emerged, both of which could greatly smooth world trends ahead - improving the rights and prospects of young women and girls and finding ways to safeguard and normalize human mobility.

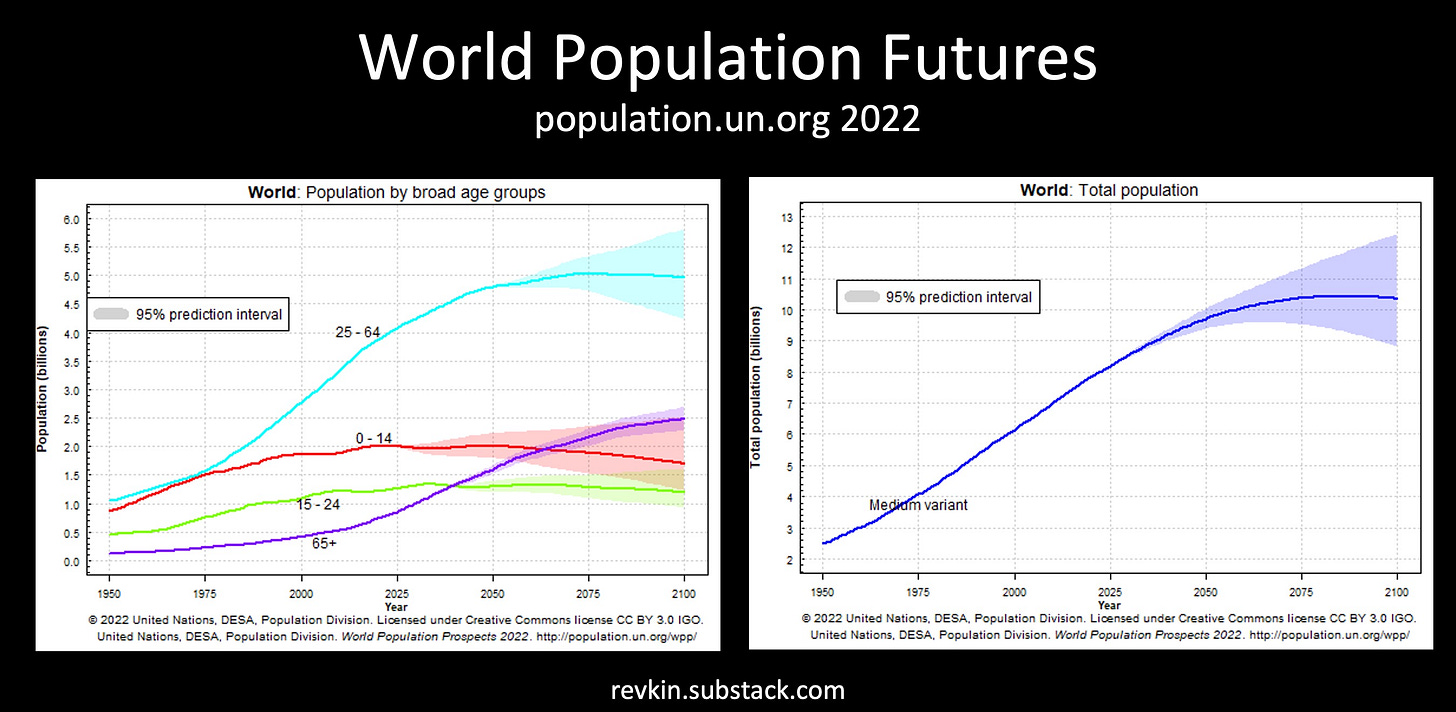

Much of what unfolds in the decades to come - particularly in places with deep poverty, high fertility rates and vulnerability to climatic and environmental hazards - depends far less on total numbers of people than on the challenges or opportunities faced by particular cohorts. One is the current cohort of 1.3 billion humans of child-bearing age, seen here as the green ribbon (15- to 24-year olds) in the UN’s 2022 population report.

And global mobility pressures, on display in the Mediterranean once again right now and along the U.S. border with Mexico, are bound to intensify given profound economic imbalances and climate change.

Addressing reproductive rights and mobility is epically hard. For family size and female health, cultural norms are just one of many barriers. At the moment there are 650 million child brides on Earth, according to Unicef. Fostering mobility seems a no brainer in a world of aging, shrinking populations and fast-growing populations. But the spreading convergence of nativism and populism in world regions with low fertility rates is a profound barrier. (For more on this troubling trend, read this 2020 book chapter by Eirikur Bergmann, a professor of politics at Bifrost University in Iceland.)

Here are my guests and their key points and priorities:

Kathleen Mogelgaard, president of the Population Institute, an international nonprofit group that seeks to promote universal access to family planning information, education, and services. This short video by her organization, part of a package on the path Beyond 8 Billion, conveys a key reality - that population dynamics, shaped largely by women’s prospects, can greatly cut or worsen vulnerability to climate hazards:

If you’ve followed my writing for awhile, you’ll see I’ve long focused on the connection between women’s welfare and environment. Read my 2014 Dot Earth post on fostering “sustainable motherhood” for starters.

Joe Chamie, a consulting demographer who is a former director of the United Nations Population Division and author of numerous publications on population issues, including his recent book, "Births, Deaths, Migrations and Other Important Population Matters."

I’ve relied on his insights and views for more than a decade, including in my 2007 post on the notion of regional population cluster bombs and my 2009 New York Times Dot Earth post asking “What’s the Right Number of Americans.”

Read his Inter Press columns here, including his look at the 8 billion threshold and forecasts of population implosion.

Here’s a key takeaway from Chamie in our chat (with some smoothed language):

On international migration cooperation, basically [we’ve] done very little over the last five, ten years. We haven't done much at all because of national sovereignty. The thing that's ironic, especially in Europe and the developed countries, they want to increase birth rates, but they don't want any migrants. They want people of their own. This goes into these cultural biases. People are pressing to having a larger population because we want more of us and less of them.

But this issue of 8 billion people and growing, and the inequities, if you look at what's going on in countries like Niger, Haiti, Bangladesh, Pakistan…, they're living in conditions that are very, very difficult. And there is going to be an enormous clash between the people that want out - estimated at about a billion people that want to move to another country - and those people who are saying, no, you can't come in. So that's going to have spillover effects. And maybe that's one way to get [policymakers’] attention.

Céline Delacroix, director of the FPEarth.org project of the Population Institute and adjunct professor at the University of Ottawa’s School of Health Sciences. With Nkechi Owoo from the University of Ghana, Delacroix is currently documenting voices of sub-Saharan Africans on the relationships between reproductive rights, population dynamics and environmental sustainability.

I encourage you to read her short essay “Ecology and Empowerment” contributed to The Great Transition Initiative’s discussion series The Population Debate Revisited. Delacroix writes: “[P]opulation growth can be effectively addressed by expanding the autonomy and the exercise of reproductive rights for women and by removing their barriers to safe and effective family planning…. This category of rights, reproductive rights, is broadly underacknowledged, underfunded, and under threat. Yet the scale of progress necessary for reproductive autonomy is enormous: nearly half of pregnancies around the world are unintended…. All interventions likely to have lasting positive effects on population trends are based on steps taken for other good reasons: education for women and girls, comprehensive sexuality education, expansion of women's rights, and unfettered access to effective family planning services and commodities. If the public better understood this key fact, addressing population would gain attention and acceptability as an important public topic and a noble cause deserving global effort.”

This diagram from her project conveys the value of reproductive freedom for those focused on pursuing climate and environmental sustainability.

Charles Kabiswa, a Ugandan who is executive director of Regenerate Africa, a nonprofit organization working to rebuild deteriorated social, ecological, health and economic systems to benefit people, nature and the climate across Africa.

In our conversation, Kabiswa stressed how the logic of meshing women’s rights, family planning, ecological and agricultural sustainability is easier to articulate than to accomplish on the ground, particularly in regions with high fertility rates, high climate vulnerability and limited government capacity:

[Given] the siloed minds of the politicians, the governments and the civil society, we don't seem to see the interconnectedness even when we do have all this evidence. So it is very worrying that the much-needed attention is not coming through.

Terry McGovern, professor and chair of the Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health and the director of the Program on Global Health Justice and Governance at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

I asked her about the role of academia and, in the context of both family planning policy and migration, McGovern described the same kinds of impediments Kabiswa spoke of:

There's so much that's about governance. And frankly this is also true in the migration context. We don't have an international agreement that bestows any kind of status on people who have to move because of the climate disaster, right? So I think academia really is very important here, but we have to move out of our silos and we have to work across disciplines. And that's very much what I've been trying to do. It's not easy because we speak totally different languages. But I think it's absolutely essential. One of the things that I think is a problem currently in the US is that of course in the abortion context everybody's saying, let's fund the ground, let's fund the ground, let's fund people to move women across states, etc. But we actually need to step back and look at strategy, and academia has a really important role in that.

Her points about migration recalled a January 2021 Sustain What webcast I ran on this glaring need, focused on a Model International Mobility Convention: The event was titled Stop Debating Climate Dislocation and Start Enhancing Climate Mobility. I hope you’ll give it a look when you have time:

More on human numbers, vulnerability and futures

I was born in the year 2.794. I mean at the point when there were 2.794 billion humans on Earth - 1956. Looking at the graph below, you could almost say the subsequent population surge must be my fault (or my Baby Boomer generation’s). I used a tool posted in 2011 by Population Action International that no longer exists.

Of course the propellant for this surge was modernity - from fossil fuels and fertilizer to medical care and urbanization and more.

I came of age as the first wave of population catastrophism surged to a crest in the late 1960s, crystallized in Paul Ehrlich’s Population Bomb bestseller. He’s a brilliant scientist and provocative communicator. The Tonight Show propelled the book more than any reviews. But he and others got this concept dangerously wrong, in ways that spun out into devastatingly ill-designed population control efforts.

Please watch the excellent Retro Report program on this saga: Population Bomb: The Overpopulation Theory That Fell Flat.

Unfortunately this phenomenon, of an unscientific narrative catching hold, is playing out yet again via what you can call the climate collapse movement and a spate of books and articles foreseeing humanity’s demise.

For a deeper data-based review showing how deeply-flawed ideas like this can not only catch hold but persist for generations, read Roger Pielke Jr.’s fresh Substack post on the myth of the population bomb:

These posts of mine predating my Substack migration are relevant as well:

Finally, well before I launched this Sustain What newsletter at Bulletin (and now here) I hosted an incredibly illuminating conversation on humanity’s growth spurt and what comes next with the Joel Cohen, the famed demographer who wrote the landmark book “How Many People Can the Earth Support?”, the Kenyan futurist Katindi Sivi and tech-focused geographer Christopher Tucker: How Many Billions Can a Heating, Pandemic-Wrapped Planet Support?

The sheer complexity of this problem makes it hard for even allied political forces to communicate effectively with thei constituents, and makes it easier for racist nationalists to sow fears and despair that only fascists can manage. Your work here continues to be of the highest importance and I only hope your readership grows in proportion to this terrifying reality. Thanks Andy.

https://www.euronews.com/next/2022/11/15/sperm-count-drop-is-accelerating-worldwide-and-threatens-the-future-of-mankind-study-warns Sperm count drop is accelerating worldwide and threatens the future of mankind, study warns. Mostly likely this is from pollution impacts worldwide.