A Murder Confession in the Amazon Means Little Without Big Changes in Brazil’s Relationship With Rain Forest Guardians

Two arrests and a confession could lead to justice in the murders of a journalist and an Indigenous champion, but the Amazon remains perilous for its first peoples and those defending them.

Track my companion live video webcasts at the Columbia Climate School Sustain What page. Watch today's Friday news review for more on this evolving story:

UPDATED

There's a chance for some clarity and courtroom justice on the violent fringes of the Amazon rain forest given news reports late today indicating that one of two arrested suspects confessed to participating in the murders of a Brazilian Indigenous expert, Bruno Pereira, and a sustainability-focused journalist, Dom Phillips.

According to CNN Brasil, which broke the news along with Band News, police said the suspect, Amarildo Oliveira da Costa, claimed to have helped dispose of the bodies but another person shot the victims. According to CNN, "[H]e admitted that Pereira and Phillips were murdered because of complaints about illegal fishing in the region."

Indigenous communities in the Javari Valley where the men disappeared have faced sustained violence and territorial invasions by poachers with relationships to drug cartels. Much of the progress in the case has come from Indigenous or Indigenous-led search parties, as this remarkable Channel 4 video shows:

If the reports hold up, there is the welcome prospect of justice being served. But such progress offers little comfort to the families, colleagues and closest circles of Pereira and Phillips, who were last seen on June 5th heading out together on the River Itaquaí in the Javari Valley - a vast Indigenous territory in the western reaches of the Amazon River basin increasingly beset by violence perpetrated by drug runners, poachers, illegal loggers and other disruptive and dangerous elements.

Whatever happens in a courtroom to address this particular tragedy, the turbulent conditions that have built in the region through the combination of remoteness and the anti-Indigenous, pro-extraction presidency of Jair Bolsonaro will persist if he is reelected in October. (For the moment, at least, that seems unlikely, but politics these days are as tumultuous in Brazil as in the United States.)

The two men had been conducting interviews in Indigenous communities for a book Phillips was writing on development pathways and obstacles in that part of the Amazon. He was a freelance contributor to The Guardian and other outlets.

According to media reports, Pereira had received many death threats, particularly for work helping create patrols to counter poaching.

Amid a murky flood of fragmentary and inaccurate updates, Indigenous and government teams had searched for the two men through Tuesday, even as some family members expressed growing conviction they were dead - almost surely victims of the predatory forces unleashed on Brazil's remote resource frontiers by Bolsonaro's nationalistic and racist rhetoric and policies.

The case appeared to crystallize a bit on Tuesday as police in the river town of Atalaia do Norte told reporters they had arrested a second suspect, Oseney da Costa de Oliveira, for "alleged aggravated murder." He is the brother of Amarildo da Costa de Oliveira, a fisherman who was arrested last week and is reported to have confessed.

Given the swirl of flip-flopping reports in recent days, like those below, it remains far too soon to say case closed.

Keep track via nonstop Guardian coverage by Tom Phillips on the scene in the Javari region, Andrew Downie and others.

Guardian coverage of the vanishing of Pereira and Phillips

Phillips headed from Britain to Brazil in 2007 while a music journalist, but a decade later had settled in as a foreign correspondent and by 2018 was fixated on the fate of the Amazon and its first peoples. He began working with Pereira as a source-mentor-guide that year when they and the photographer Gary Calton went on an extended and arduous journey to assess the situation of some of the region's most isolated tribes. Explore Phillips's Guardian article here and watch this short video clip:

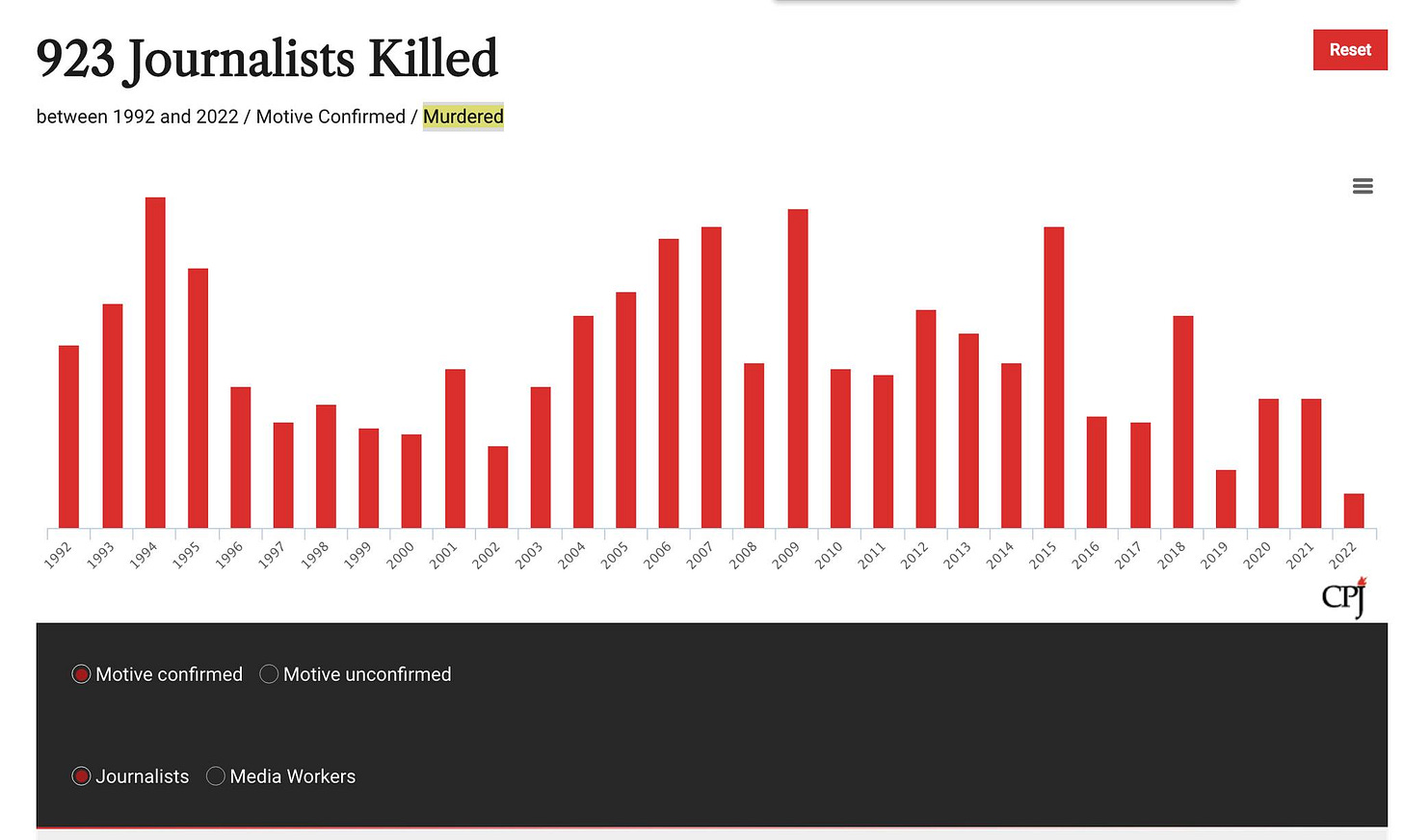

With this horrible slaying Phillips joins the too-long line of 923 journalists murdered since 1992 for doing their job, as tallied by the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Given the circumstances leading up to the killing of Phillips and Pereira, I'm recalling in particular the murders of Hang Serei Odom and Taing Try, Cambodian reporters killed in 2012 and 2014, respectively, for digging in on illegal logging, and Suon Chan, a Cambodian journalist slain in 2014 while reporting on illegal fishing.

Amazon threats transcend Bolsonaro

It's important to note that forces driving deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon transcend the "Bolsonaro effect." He became president in 2019, yet data from the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project show profound spikes in deforestation and fire starting in 2016.

It is also worth noting the decades-long history of spasms of violence, forest clearing and burning and illegal seizures of land or resources from Indigenous territories and holdings of traditional forest communities of rubber tappers.

I spent three months in the Amazon in 1989 reporting "The Burning Season," my book on the 1988 assassination of forest defender Chico Mendes. The death counts in that decade were far higher than today - a reality that is scant solace for families of those killed lately.

The year of Mendes's killing (at the hands of a murderous ranching family aided by powerful figures in the state of Acre) also saw the infamous "Helmet Massacre" in which 14 Ticuna Indians were killed and 23 wounded in Amazonas state along the Brazil-Peru border.

As Cultural Survival recounts, "One of the survivors said that a group of about 120 Ticuna men, women and children was awaiting news of an official inquiry into the case of a lumberman accused of killing a Ticuna-owned cow when about 20 white lumbermen attacked them with automatic weapons."

I reached out for reaction to current events from Linda Rabben, an anthropologist and campaigner for the rights of forest peoples who investigated the lingering impacts of the Ticuna massacre. Here's her reflection:

I traveled to the Javari River Valley in 1993 on an Amnesty International mission. I visited several Ticuna indigenous villages where survivors of the 1988 massacre of 14 men and boys by a land grabber lived. Amnesty groups in several countries wanted to donate relief funds to them. Widows and mothers of the victims told me they needed motors for their canoes and building materials. After I made my report, Amnesty groups donated about $7,000 to them.

I went to the town of Benjamin Constant to meet my guides, Ticuna activists who lived in town and managed a small museum and library of Ticuna culture. They put me up at a friend’s house, telling me it wasn’t safe for foreign supporters of Indians to stay at the local hotel. Whites in the area used to hunt Indians for sport, they told me.

The author of the massacre, which the Brazilian government classified as genocide, was never brought to justice.

This visit brought home to me how precarious the security of Brazil’s Indigenous people is, even in their own reserves. The killing of indigenous-rights and environmental defenders is not news in Brazil. As the Brazilians say, “Já vi esse filme” - "I’ve already seen that movie."

"As the Brazilians say, 'Já vi esse filme' - 'I’ve already seen that movie.'"

Someday in the months to come, there will be a trial for the arrested suspects - or someone else depending on how things play out. It will be similar to the one I reported on in December 1990, for the murderers of Chico Mendes.

Andrew Revkin photos

There'll be a media frenzy. There'll be a verdict. And life will go on in communities across the world's violent resource frontiers, or be brutally interrupted without better governance and accountability.

No matter how this latest Amazon tragedy plays out, it will take years to markedly shift the dynamics driving the lawless behavior that has made many parts of the vast river basin unrelentingly dangerous for rights seekers, truth seekers and Indigenous and traditional communities facing drug smugglers, miners, poachers and land grabbers.

Most of the killings don't make for major daily headlines like those at the moment, which today elicited a pledge of help from British Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Read this story on the Catholic news site Crux for the latest from the Pastoral Land Commission, which has been tracking killings in land disputes in Brazil for decades: Indigenous deaths in Brazilian land disputes skyrocket in 2021.

And this Mongabay story shows the grotesque intensification of development pressures in Indigenous lands: Illegal mining footprint swells nearly 500% inside Brazil Indigenous territories.

Bolsonaro was elected on a rural-focused “beef, Bible, and bullet” platform that still has pull in the hinterlands.

Last year, Indigenous rights lawyers and organizations filed requests with the International Criminal Court in The Hague seeking charges against Bolsonaro for genocide and incitement of crimes against humanity, as well as possible charges of "ecocide."

Scott Wallace, the longtime National Geographic journalist and author of an acclaimed book on Brazil's isolated Amazon tribes, explored this question in a recent talk at the University of Connecticut, where he is a journalism professor:

Paths to safety and sustainability start on the ground

Luckily these days, there's far more real-time reporting and surveillance of illegal activity in such regions than there was decades ago. Explore the reports of the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project.

But no amount of satellite imagery will matter without empowering and protecting those on the ground in Indigenous or traditional communities who are front-line sentinels. Read this Mongabay report on how Indigenous communities are using technology to report environmental crimes.

The power of such a presence was clear well before the Web, in 1989, when I accompanied a group of rubber tappers, all colleagues of the slain leader Chico Mendes, as they spread word about some illegal cutting, piled into a truck, confronted the chain saw crew and used the saws to dismantle the illegal encampment.

Andrew Revkin photos from "The Burning Season"

Much of the capacity for guardianship rests with Indigenous organizations like the Union of Indigenous People of the Valley of Javari, or UNIVAJA (follow them on Instagram at @univajaoficial); COICA (Coordinadora de las Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazónica), the umbrella group for Indigenous organizations across the Amazon Basin; If Not Us Then Who, a network and collective fostering Indigenous communication capacity and impact. Also explore the work of Niatero - an environmental organization committed specifically to boosting the capacity for guardianship.

And, happily, there are far more journalists in Amazon regions at risk than there were a decade ago. Last week, as the search for Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira played out, dozens of journalists receiving support for rain forest reporting from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting met in Washington, D.C. They posed for a photo on June 10th to express solidarity and demand answers.

Reading and Resources

The Brazilian journalist Eliane Brum, who lives in another corner of the Amazon, filed a potent column for The New York Times: "Was a British Journalist the Latest Victim of Bolsonaro’s War on the Amazon?"

Also please read this Guardian op-ed by Lucy Jordan, who is the Brazil correspondent for Unearthed, a publication of Greenpeace: "The disappearance of journalist Dom Phillips in Brazil should leave you incandescent with rage."

You can meet Jordan - and hopefully one or two more journalists focused on this terrible case - in our Columbia Climate School Friday news review at 1 p.m. U.S. Eastern time.

These Sustain What episodes are highly relevant and I hope you can watch and share them when you have time:

To Preserve Tropical Forests, Empower Local Communities

How Rights for Forest Guardians Can Break the Pandemic Circuit, Save Species and Slow CO2 Rise

Linking Classrooms, Amazon Threats and Newsrooms through Data

Parting song - Saga Da Amazônia

To my ear, no piece of music better captures the wonder, spirit, tragedy and hope embodied by Brazil's portion of the Amazon River basin than "Saga Da Amazônia," written by Vital Farias in 1982. Please listen while you read, and let me know what a place like the Amazon means, or should mean, to the world outside those amazing green expanses.

This live version, preceded by a poem recited by the actor Rolando Boldrin, gives me chills every time I watch.

Here's an excerpt from a creative and updated translation by Peter Lownds:

If, my friend, the forest had feet I’ll tell you what

It would’ve run for dear life before the trees were cut

With bunches of nuts and fruit we picked when ripe

Which disappeared so fast we had no time to gripe

Monkeys, lagoons, air full of moisture from inland seas

Dragon devours the forest with no concern at all for these.

And those who live in this forest, what on earth must they do?

Forest-dwellers, rubber-tappers, sloths, anteaters, turtles too

All of them running for their lives through burning brush

Through land once thick with trees amid debris they rush

Deed forgers cheat landholders robbing them of their livelihoods

Only injustice and persecution remain where once there were woods

Native hunters and gatherers became peons, New World serfs

They are the nameless ones who resisted and died on alien turfs.

And, of course, I can't hear Vital Farias's Amazon epic without recalling Gordon Lightfoot's incredible "Canadian Railroad Trilogy," commissioned by the CBC in 1967.

I can't count how many times Brazilians questioned my concern for Chico Mendes or the rubber tappers' Indigenous allies by alluding to the genocidal history of North American conquest. And of course they're right.

Here's a reexamination of Lightfoot's song considering the vantage point of the Indigenous nations ravaged by what those rails brought.

Your turn

There is a GoFundMe campaign for the families of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira.

Postscripts

The veteran journalist James North made this important point in a tweet:

"The fisherman who confessed to killing environmental heroes #DomPhillips and #BrunoPereira is just one part of the tragedy. In truth, the Amazon rainforest is threatened mainly by corporate mining and oil, abetted by #Brazil's complicit government."

Help build the Sustain What community

Any young column needs the help of existing readers. Tell friends what I'm up to by forwarding this introductory post or sending an email here (substitute the addresses you're sending to for the dummy "revkin.revkin" address).

Thanks for commenting below or on Facebook.

Subscribe here free of charge if you haven't already.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues.