Why a Twitter Implosion Could be a Disaster in Disasters

Emergency preparedness experts and professionals wisely warn of peril if the unique attributes of Twitter in tracking and responding to unfolding calamities are lost

In the first days of Elon Musk’s tumultuous takeover of Twitter, I alluded briefly to deep concerns being expressed by people working in emergency management and response over the potential threat to public safety and resilience should Twitter’s unique role as an open public square be badly damaged or destroyed.

That chorus of concern is growing.

Insert, 11/17, 4:30 pm ET - Jim Moffitt, a Twitter developer relations staffer who helped drive the use of Twitter’s external data interface (API) for extreme weather tracking and response, has quit. This is a bad sign.

Moffitt just tweeted that this was “a hard decision to make, adding, “The good news is that as long as the Twitter API exists, we can work together to build real-time notification systems.”

Sam L. Montano (@samlmontano) of the Massachusetts Maritime Academy nailed a host of issues in her Substack Disasterology newsletter, noting:

People who work in emergency management use Twitter for all kinds of formal and informal uses. Arguably most important is the role Twitter plays in spreading lifesaving information during a response. It’s via Twitter that the world often first learns a disaster has even occurred. It’s where survivors can speak for themselves and share their experience and their needs. It’s where we come together to make sense of a disaster.

Mark Shapiro (@ETSshow), a physician who hosts a podcast on the interface between health care and society, tweeted this question:

Emergency management services around the country use Twitter to communicate in real-time. I have used multiple Twitter accounts for info during wildfires. How will they fill this information gap if Twitter shuts down, as some are predicting?

I don’t foresee Twitter being shut down in the long run; a phoenix-like reemergence is almost inevitable given its value, even if bankruptcy is a short-term threat. But I do think it’s being badly damaged. I don’t see any competitor with anything remotely like Twitter’s utility.

Caroline Orr Bueno (@rvawonk), a behavioral scientist at the University of Maryland studying disinformation and cognitive security during crises, has been relentlessly posting on threats to public understanding and security if Twitter’s unique capacities erode or vanish. But her Monday thread on Twitter’s utility in emergencies is the most relevant one to this post. She started by saying:

One thing that keeps me up at night right now is the possibility that Twitter’s potential death spiral will coincide with a major regional/national/global crisis. For better or worse, Twitter is a crucial disaster comms tool, and we don’t have a replacement for it.

Twitter has been a vital source of information, networking, guidance, real-time updates, community mutual aid, & more during hurricanes, wildfires, wars, outbreaks, terrorist attacks, mass shootings...etc. It's not something that can be replaced by any existing platforms.

If Twitter suddenly stops working or if huge swaths of the population can't access it during a crisis, the result will almost certainly be preventable suffering & death. Elon Musk needs to stop treating this like a playground, and start protecting it as vital infrastructure. (Read the rest on Threadreader here.)

I sure hope @elonmusk is listening.

Through Sam Montano’s Twitter home page, I began exploring the hashtag #EMGtwitter and found another layer to the Elon Musk question - how much emergency management depends on two systems he now controls: Twitter and Starlink, the Internet he’s building in orbit, which mobile crisis managers rely on, Ukrainian armed forces rely on, and I rely on for connectivity in rural coastal Maine).

Read this LinkedIn post by Rakesh Bharania, which I found via Twitter: For Better Or Worse? - Elon Musk's Massive Influence in Emergency Communications.

Megan McCluskey (@MegzyM27) at Time just posted an excellent overview of the impacts of a less-reliable Twitter during crises. This input from Christina Wodtke (@cwodtke), a lecturer in computer science at Stanford, shows the peril in the propagation of blue checks for cash (purchased visibility and the sheen of credibility):

If trolls and bad actors are taking advantage of Twitter’s megaphone effect during times of uncertainty, it can give rise to an even more dangerous situation, Wodtke says. “If users see a piece of information from a blue check account and the name looks the same as the name of an official entity, then they’re going to believe it’s true,” she says. “This was a poor choice on a safety and misinformation level because it says now anybody can be a source of trust. And not everyone can be trusted.”

Why just Twitter?

Facebook can have similar value in emergencies. I wrote in The Times about how villagers in Nepal used the Facebook page of the Darjeeling Chronicle newspaper to appeal for helicopter aid after the 2015 earthquake.

And, as I wrote a few days ago, the Trinidad & Tobago Weather Center launched on Twitter in 2014 by the broadcaster and journalist Kalain Hosein (@kalainh) is just one of countless examples of getting reliable information to the public in emergencies.

But Facebook is still a closed system - not open to the full online universe. And having spent time on Mastodon in recent days (mastodon.green/@revkin), I see lots of neat, but siloed Slack-style conversations, but there’s no wide-view discoverability (yet).

Insert - On Twitter, someone asked what Mastodon lacks that limits its utility in emergencies. I responded with SEARCH, pointing to this revealing thread by @ShortFormErnie:

Insert, 4pm ET - As I’ve written, Twitter’s API (application programming interface) has also been harnessed for emergency awareness and response in way that can’t be replicated elsewhere. Much of that progress has been made thanks to Jim Moffitt in Twitter developer relations. Here’s hoping that asset doesn’t go away.

Since #SanDiegoFire in 2007, a role in emergencies

It’s worth noting again that the first widespread use of a #hashtag occurred during an unfolding wildfire emergency in San Diego in 2007, just months after the Mozilla employee Chris Messina invented this device. (Watch my chat with Chris about this moment.)

This 2013 Forbes article by Samantha Sharf nicely lays out the transition from Messina’s initial tweeted proposal for a # sign ahead of a search term to the real-time value of #SanDiegoFire:

He decided to lead a grassroots movement, writing detailed blog posts about the hashtag’s benefits, drawing mockups of “hashtag channels” and using hashtags everywhere. In fact, co-workers soon noticed Messina using hashtags everywhere.

“It began with Twitter but eventually, I started to use hashtags in my texts, emails, and even my Google Doc titles,” he says. “It made it easier to search all of my own content.”

It took a few months for others to see the value. Oddly enough, a natural disaster helped Messina’s movement spread like wildfire – literally.

On October 22, 2007, San Diego resident Nate Ritter turned to Twitter to break the news about a historic forest fire:

Ok, I'll be twittering the San Diego fires now. — Nate Ritter (@nateritter) October 22, 2007

He became a one-man news crew. The television and radio blasted in Ritter’s living room as he sat on his sofa, listening intently and funneling updates through Twitter. He even roamed the streets, asking for first-hand reports and tweeting about evacuation sites, meeting points and places to gather supplies. But with only 350 followers, Ritter updates weren’t getting very far.

That’s where Messina re-enters our story. Turns out he and Ritter were buddies from BarCamp. Messina saw his tweets and sent him a direct message at 4:02 PM: “ever heard of hashtags? You could use #sandiegofires in your tweets.”

A few hours later, Ritter tweeted:

#sandiegofire south shores, ski beach open to motor homes. fiesta island is open to first 500 livestock that come in. — Nate Ritter (@nateritter) October 22, 2007

Soon enough, many other users started tweeting “#sandiegofire” and tracking it for crucial updates (“tracking” was a short lived featured that served a purpose similar to the hashtag). The hashtag had finally proved its usefulness in a moment of dire need and across a large audience.

I really would like to hear from you on this? Are you off or on Twitter? Have you relied on it in emergencies? Radio? Something else?

Also read Casey Newton of course:

There’s much more to say on this, but I have to get back to tracking outcomes and issues at the COP 27 climate treaty talks in Egypt. I’m running a Columbia Climate School Sustain What news review focused on the negotiations on Friday at 9 a.m. US Eastern time with at least two people who’ve been dug in there throughout - the climate adaptation expert Richard JT Klein (@rjtklein) and E&E News climate reporter Jean Chemnick (@chemnipot). Click the link on her name to explore her story flow.

Watch here:

Parting tweet

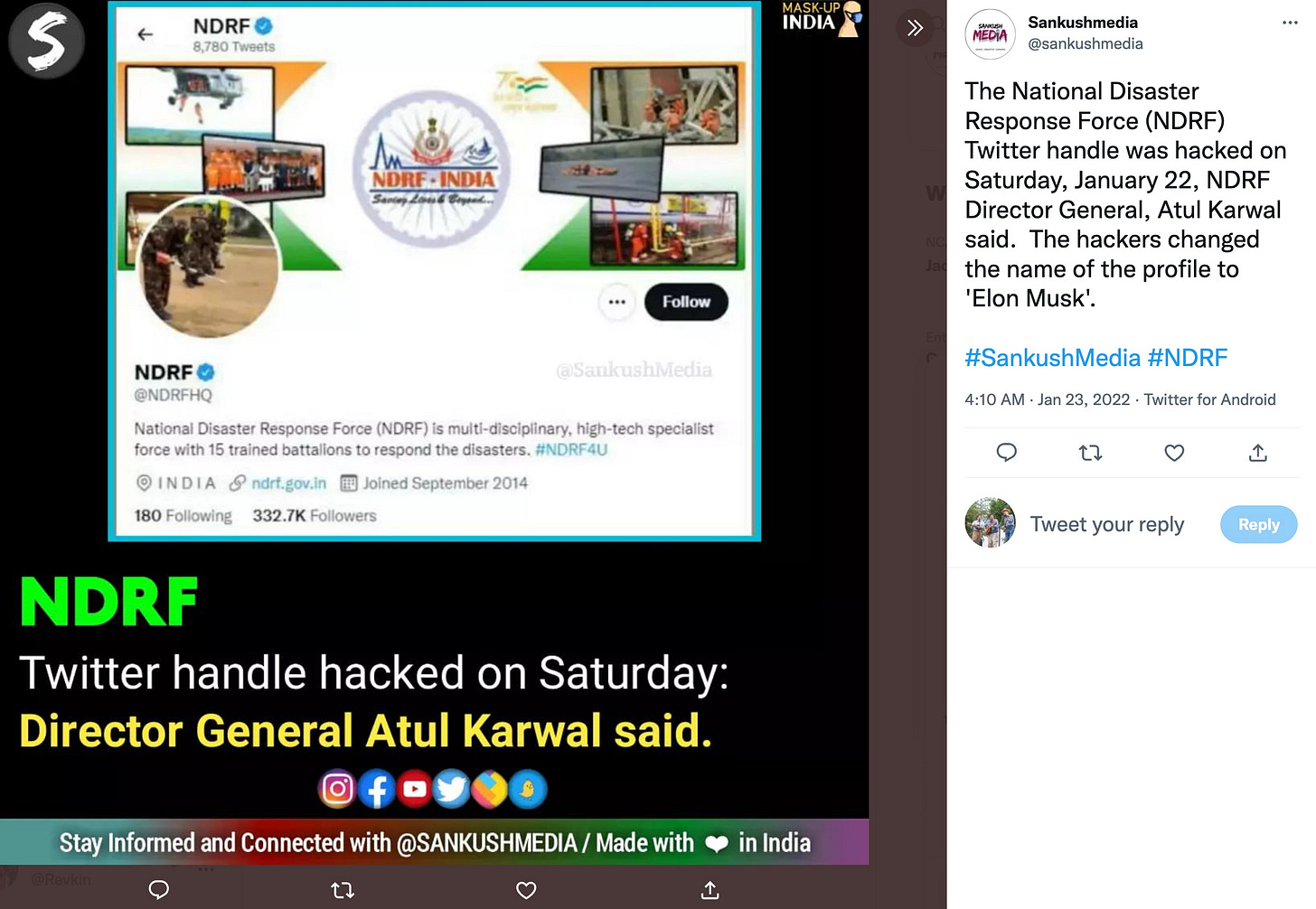

It’s worth noting that the potential for dangerous hackery related to disaster management has existed well before Musk’s latest moves. See this tweet from an Indian news agency in January:

I have resisted Twitter, have hardly ever looked at it, & won’t really care if it vanishes. But you have reminded me that when there are wildfires near my home, that’s where I get my info, from the county sheriff’s tweets.

"If Twitter suddenly stops working or if huge swaths of the population can't access it during a crisis, the result will almost certainly be preventable suffering & death." > Seriously? "Huge swaths of the population" don't even have a Twitter account, anywhere in the world. The total user base is 5% of the population of the world. There are dozens of other ways to disseminate emergency information > it was disseminated even before Twitter was dreamed up. Sure, in the meantime we have actively dismantled public services that did just that, because, well, a dysfunctional privately-owned toxic platform is surely better.