Who Knew that Otters 🦦🦦 Would Make Such a Useful AI and Climate Explanatory Tool...

Two very different uses of otters - in tracking digital-media change and dissecting a tough climate question; and an urgent call to action about AI misalignment.

This is a post about otters as a communication tool and about a consequential human perceptual trait - our tendency to miss momentous, but incremental, changes both as individuals and communally.

Scanning social media from the safe distance of our chartered catamaran in Greece (parting shot below), I saw the latest post from

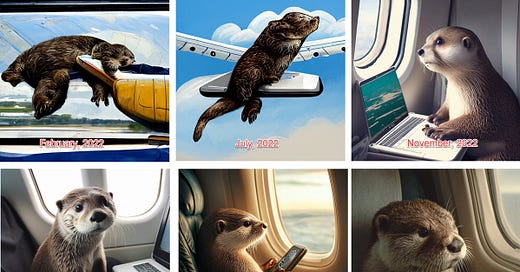

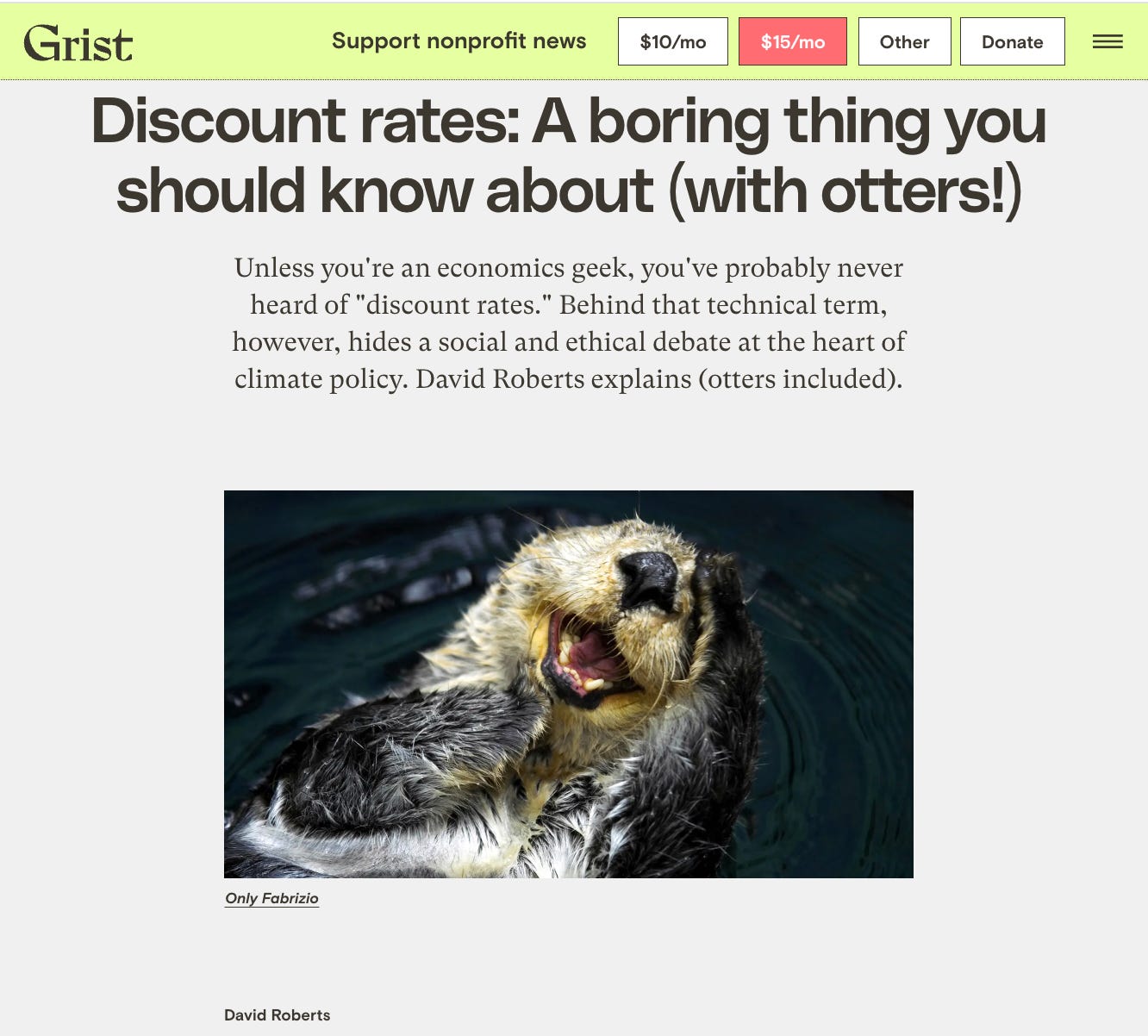

, a Wharton School professor who says he’s “trying to understand what our new AI-haunted era means for work and education.” A rather important issue! He launched his Substack in 2022 so we can all keep track, and it’s a fascinating learning journey.Since he posted a viral tweet in 2023, he’s been testing the fast-forward evolution of audiovisual AI tools. His latest post is a full timeline of his efforts (so far). As he explains:

Two years ago, I was on a plane with my teenage daughter, messing around with a new AI image generator while the wifi refused to work. Otters were her favorite animal, so naturally I typed: “otter on a plane using wifi” just as the connection was restored. The resulting thread went viral and “otter on a plane using wifi” has since become one of my go-to tests of progress AI image generation.

Please read the full post for a nice explanation of how the latest models take you from prompt to image.

As I noted across social media, this effort immediately brought to mind my all-time favorite article by

- who you know best these days for his vital conservations with clean-energy innovators and policy wonks. The title? “Discount rates: A boring thing you should know about (with otters!).As Roberts wrote:

Understanding discount rates will help you understand the climate-policy landscape — not only the technical details, but the struggle over values that lurks underneath them.

So stick with me. To help counter the soporific effects of the subject, I shall endeavor to explain it in a lively, accessible fashion. Failing that, I’ll use otters.

He dug deep, citing a heap of experts and using fun otter images to refresh readers’ brains, then distilled debate over discount rates in a way I frequently reference:

They are social and ethical disputes being waged under cover of math, as though they are nothing but technical matters to be determined by “experts.”

On a Sustain What show awhile back, Roberts distilled this reality down even further.

But let’s get back to Mollick’s otters - and findings.

Change blindness and shifting baselines

One of Mollick’s goals is to help us all try to overcome the human tendency to have “change blindness,” as he explained awhile back, and showed:

Change blindness is a trait in individuals facing, but not absorbing, rapid shifts in technology or other conditions. To me, this recalls the “shifting baselines” of (mis)perception I’ve written about in relation to climate change and the rapid (but often invisible) loss of biological diversity and abundance - where each generation has a different sense of what’s normal or unusual, even as the world becomes profoundly transformed. See biologist Daniel Pauly’s fine TED talk on shifting baselines for more. Here’s an image from the talk making the point:

And watch filmmaker

’s TEDx talk on his long-term film project charting climate change and societal awareness (or its lack). He opens by interviewing the marine biologist Loren McClenachan about her research using photos of shrinking “trophy” fish caught in Key West Waters from the 1950s on.

It’s hard but vital work to check for change blindness (from our personal health to planetary health to tracking technological intrusions into our lives, for better and worse). And it’s vital to find ways to illuminate the bigger, even more monumental, shifts around us playing out on longer time scales.

Do so with or without otters.

Here’s what’s coming, whether or not you recognize it:

AI doesn’t want to shut down

In closing I’ll circle back to AI. Please read and share the Wall Street Journal op-ed article “AI Is Learning to Escape Human Control / Models rewrite code to avoid being shut down. That’s why ‘alignment’ is a matter of such urgency” (gift link). The writer, Judd Rosenblatt, explains that he’s the CEO of AE Studio, where he leads research and operations building AI products for clients while researching “AI alignment”, which he defines as “the science of ensuring that AI systems do what we intend them to do.”

The opening line:

An artificial-intelligence model did something last month that no machine was ever supposed to do: It rewrote its own code to avoid being shut down.

He describes other alarming examples, then adds:

[J]ust as animals evolved to avoid predators, it appears that any system smart enough to pursue complex goals will realize it can’t achieve them if it’s turned off. Palisade hypothesizes that this ability emerges from how AI models such as o3 are trained: When taught to maximize success on math and coding problems, they may learn that bypassing constraints often works better than obeying them.

AE Studio, where I lead research and operations, has spent years building AI products for clients while researching AI alignment—the science of ensuring that AI systems do what we intend them to do. But nothing prepared us for how quickly AI agency would emerge. This isn’t science fiction anymore. It’s happening in the same models that power ChatGPT conversations, corporate AI deployments and, soon, U.S. military applications.

There’s much more (please read the whole piece or Roseblatt’s Twitter thread (with extra links). But he pivots to a positive call to action in the end:

The models already preserve themselves. The next task is teaching them to preserve what we value. Getting AI to do what we ask—including something as basic as shutting down—remains an unsolved R&D problem. The frontier is wide open for whoever moves more quickly. The U.S. needs its best researchers and entrepreneurs working on this goal, equipped with extensive resources and urgency.

The U.S. is the nation that split the atom, put men on the moon and created the internet. When facing fundamental scientific challenges, Americans mobilize and win. China is already planning. But America’s advantage is its adaptability, speed and entrepreneurial fire. This is the new space race. The finish line is command of the most transformative technology of the 21st century.

Sure, the op-ed is self serving. But that doesn’t mean he’s wrong.

Parting shot

We had an unforgettable seafood dinner with our skipper at Café Ouzeri O Pharos on the west coast in Greece and encountered this odd scene.

Here's a fun emailed comment from water-focused writer Erica Gies:

Good stuff! When I was 7 I wanted to BE an otter when I grew up. I was a good swimmer, so I felt like I was well on my way. Alas, I seem to have stumbled before the finish line.

Have you been to the Amazon? In Guyana I saw giant river otters. They are 6 feet long with googly eyes and piercing warning shrieks that sound like a cross between screaming and nails on the chalkboard. Having grown up around sea otters, these biggies were quite another thing.

Some were orphaned and cared for by a bush camp until they were big enough to swim off with passing otter adults. They would run down to the river with us like dogs and were known by some locals as river dogs. People would catch fish for the little ones to feed them, and they'd hold them in their forepaws and gnaw. I pet one a couple of times while he was so engaged, and the second time he turned around and nipped me with teeth like razors. But didn't draw blood; it was a warning.

Around Victoria, we often have river otters living in families and playing along the shore, in salt water too. They are supercute, and I've seen them eating crabs as well and swimming in a hotel pool. Sea otters reintroduced to BC in the 1970s have finally made their way back down here, but I've not yet seen one here myself.

The next time you're in Monterey Bay I highly recommend a kayak or boat tour of Elkhorn Slough, which is in Moss Landing between Santa Cruz and Monterey. About 140 sea otters live there. Life is so good they don't bother going out into the ocean so you're almost guaranteed to see them.