When Prominent Scientists Get Ahead of the Science in Search of Impact - From Smartphones to Climate

The Editor of the Journal Science explores a troubling tendency

See update at end

In a recent Science editorial examining critiques of NYU psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s wildly popular and policy-driving research and bestselling book on children and social media, the journal’s editor in chief,

, wote this:Throughout the history of science and frequently during the COVID-19 pandemic, the public’s trust in science has been undermined when scientists with large public platforms have failed to state strongly enough that their pronouncements are based on science that remains in flux. With the surgeon general’s recommendation and the inevitable pushback from Big Tech, the controversy will only intensify. Seeing past the competing agendas will require not only stronger research but a greater care in broadcasting the findings to the public realm.

Here on Substack, Thorp went much deeper (link and excerpt below) and I hope you’ll give both the editorial and his post a read, both for what is revealed about the gap between Haidt’s conclusions about phones and kids and the full state of science around harms to children from communication technology and how this relates to other efforts by (presumably) well-meaning researchers to build public presence and drive policy even as they probe emergent knowledge frontiers.

It’s not hard to find other examples in climate change science and, even more so, in pandemic science. The potential perils in pushing for attention and policy impact include the erosion of public trust that comes through what, since 2008, I’ve called a “whiplash effect.”

The perils, of course, can also include bad policy choices.

I’m told that clicking the ♡ button increases the visibility of this post on Substack. Please do so if you ♡ what I’m doing here.

Thorp’s Substack post, The Muddled Science on Teens and Social Media, includes insights from email exchanges with Haidt and a conversation with Candice Odgers, a psychologist at University of California, Irvine, who wrote a devastating Nature review of Haidt’s book.

Here’s a portion on Odgers:

I asked [Odgers] about her decision to review the book. She said that she was invited by both the New York Times and Nature, but decided to do the review in Nature. “I said to Nature that I couldn’t write anything positive,” she said. “After Nature sent me an advance copy of the book to review I wrote back to say, ‘I have been struggling in my review of this book as it is certain to be a best seller, given the fear narrative and scare tactics that are taken throughout, but the science is…absolutely awful.’” Good for Nature for continuing with the review and running it.

When I asked her why she went forward, she said, “this is a pretty damaging story for young people. If someone was going around telling a story with science about the causes of childhood cancer, we would correct the record. People are not standing up to it because the moral panic and fear around this issue has reached a fevered pitch making it a widely unpopular opinion, therefore it takes so much time to come forward.” …I contacted a number of other prominent psychologists who also disagree with Haidt’s analysis but who wouldn’t go on the record because of the time sink that it would be to jump into the fray.

And here’s a disturbing section drawing from Thorp’s back-and-forths with Haidt:

Probably the most important important thing he told me was that “It is true that I am promoting a social change program…and I am doing this before the scientific community has reached full agreement.”

Thorp lists significant concerns he, Odgers and others have with this approach, then writes:

Finally, there’s the question of whether a scientist who can reach millions — as Haidt is clearly doing — has an obligation to do more for critics who don’t have the same platform. Odgers has (for better or worse) certainly become better known as a result of all of this, but she is not on every talk show, and her ideas are not being lodged in the wider conversation. When I asked Haidt if he should have been more forthcoming about the disagreements in the book, he said, “I don’t think so.”

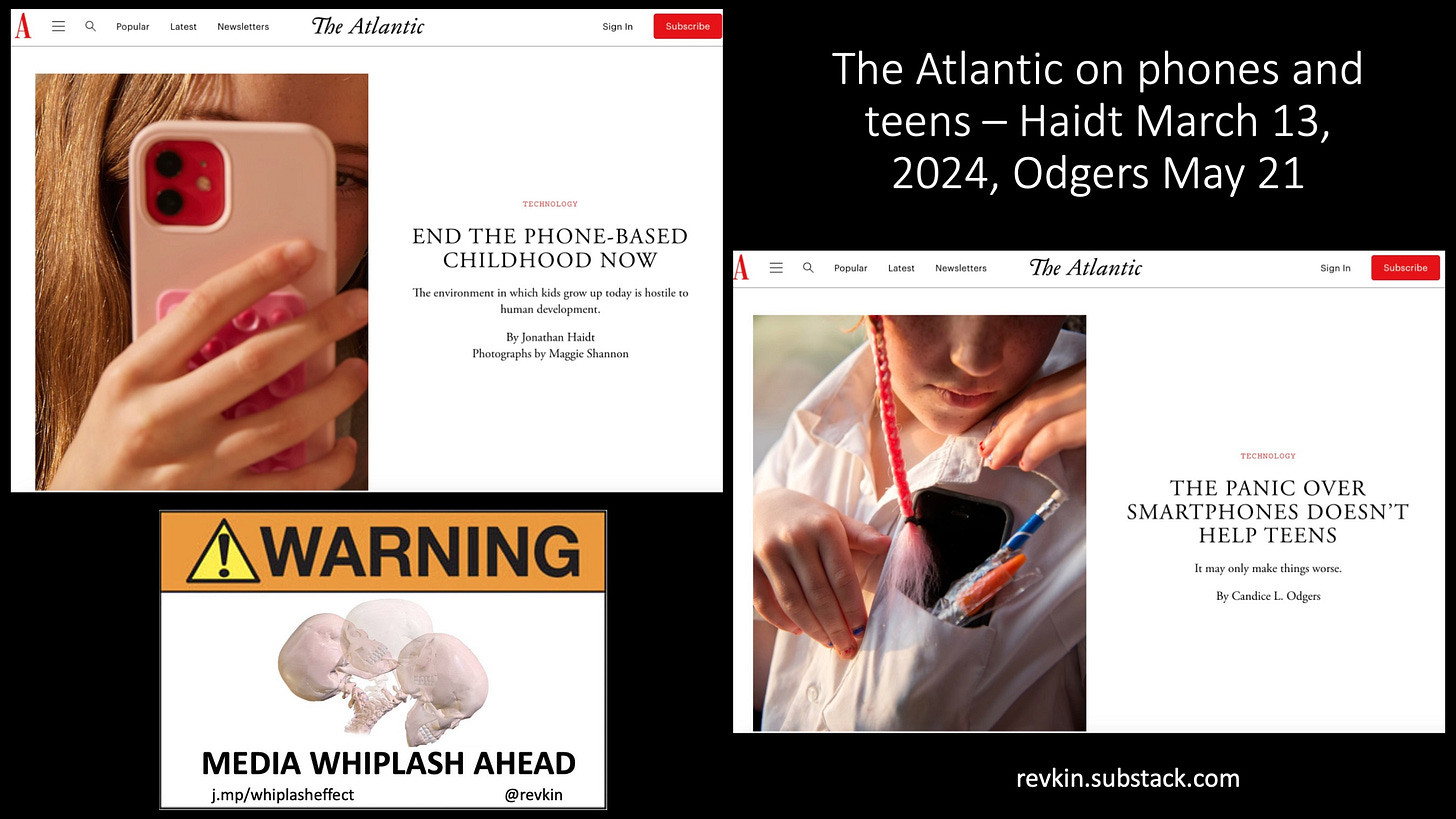

That response from Haidt is deeply discouraging to my eye. The momentum around demonizing teen social media is unstoppable, it seems, and the whiplash effect is vividly apparent at the same time. Read Haidt in The Atlantic Monthly in March: “End the Phone-Based Childhood now.” Then read Odgers in the same pages in May: “The Panic Over Smartphones Doesn’t Help Teens.”

Does accuracy matter if your goal is impact?

When I read Haidt’s line about promoting an agenda before there’s scientific agreement, it immediately brought to mind an episode in 2015 when, four months before that year’s climate-treaty talks would lead to the Paris Agreement, the famed climate science pioneer James E. Hansen posted a dramatic many-author paper warning of multi-meter sea-level rise before 2100. Hansen also held a pre-publication call with reporters arranged by publicists. Here’s a rough transcript and here’s audio:

He said the findings were too important and policy-relevant to wait for the review process to play out. He got lots of headlines:

But as the paper went through rounds of online review, the most dramatic conclusions vanished.

What other examples come to mind for you - and what remedies (if you agree there’s a problem)?

Insert, July 12 - I missed a valuable April post by

on the clash over kids and social media in April. Please read it!In a related Substack note today, Weinkle makes a vital point: “It is a mistake to make the issue about settling science. There is bipartisan agreement that something needs doing and it’s political process and debate that should decide what needs doing.”

I sense what I wrote above could be misinterpreted as saying “wait for consensus.” Amid complexity and enduring scientific uncertainty, there are plenty of policies we can all agree on related to limiting danger to kids from big-tech algorithms and danger to communities from climate extremes and global warming!

- End insert

Related - Can Any Good Come When Scientists Censor Science, Including Their Own?

I did a relevant Sustain What conversation awhile back on an inverse problem - when scientists, journals and journalists sideline findings that inconveniently clash with “pro-social” goals (X/Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn):

My guests were Cory Clark and

two of more than three dozen authors of a provocative analysis calling for clarity in gauging supposed benefits and substantial harms that come when scientific findings are suppressed for what some perceive as “prosocial” reasons.Their definition of scientifice censorship is “actions aimed at obstructing particular scientific ideas from reaching an audience for reasons other than low scientific quality."

The perspective paper, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on November 20, 2023, used surveys and other means to lay out a variety of ways such censorship occurs - ranging from journal practices choosing manuscripts to self censorship.

Cory Clark is a social psychologist and director of the Adversarial Collaboration Project at the University of Pennsylvania. Musa al-Gharbi is a sociologist and assistant professor in the School of Communication and Journalism at Stony Brook University and author of the book "We Have Never Been Woke: Social Justice Discourse, Inequality and the Rise of a New Elite."

In a related essay in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Clark and al-Gharbi say this about scientists muffling themselves:

Many academics self-censor to protect themselves — not just because they’re concerned about preserving their jobs, but also out of a desire to be liked, accepted, and included within their disciplines and institutions, or because they don’t wish to create problems for their advisees. Other times, scholars attempt to suppress findings because they view them as incorrect, misleading, or potentially dangerous. Sometimes scientists try to quash public dissent of contentious issues for fear that it undermines public trust or scientific authority, as happened at various points during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Read the paper: "Prosocial motives underlie scientific censorship by scientists: A perspective and research agenda"

The Chronicle of Higher Education essay: “Science has a censorship problem.”

Here’s a

post on the work by al-Gharbi:

Hi Andy -- As always you raise questions that highlight the many complexities and paradoxes that are endemic to complex political debates that draw on the authority of scientific expertise to resolve - whether it is the controversy over social media and teens or managing climate-related risks. As I relaunch my Substack next week (Mon. July 12) a main focus will be these specific debates but more generally the politics of expertise relative to complex policy choices. For a preview of these themes, readers should check out this past essay at my Substack: https://mattnisbet.substack.com/p/the-cayuga-lake-nuclear-debate