You've Marched for Science. What Next?

As Trump and Musk slash federal research budgets and staff, here's what scientists can do besides marching.

If you care about sustaining public health, economic vigor and American leadership in science-based innovation, it’s vital to fight the immediate threat to scientific research and scientific institutions posed by the Trump budget chainsaw and punitive funding cutoffs for institutions with diversity, equity and inclusion prorities.

In the past, plenty of Republicans in Congress resisted Republican presidents’ efforts to cut research (including the first Trump presidency). But with the second coming of Trump and his chainsaw-wielding Musk-eteer, the party is in complete appeasement mode. The long-term damage and danger is immense.

Stand Up for Science

I hope those who participated in the Stand Up for Science protests in Washington and around the country were able to reach people beyond the progressive bubble. “Science is for everyone,” the central line on the event graphics, is clearly true given how much of modern thriving is underpinned by scientific discovery and resulting innovations.

Beyond marching, a local path toward trust and impact

Marching and noon walkouts are fine as a morale- and community-building effort, but there’s always the question of who’s the audience and what’s the goal.

Just as Trumpies and Fox News delighted in highlighting the paddle- and cane-wielding Democratic lawmakers protesting during Trump’s address on Tuesday, they’ll deride the protests as elitists seeking to defend their jobs and institutions.

Many Americans, not watching Fox or CNN or Maddow, have already tuned out amid the zone flooding of Musk and Trump and clamorous defenses of democracy and rationality. Hopefully some in that mushy middle will stop and reflect on the profound importance of sustained support for science.

What can scientists do, beyond marching, to reach and activate that (dare I say it) silent majority?

Show up

I think a vital step is to follow the practice promoted for years in New York City by Nancy Holt, a young chemist with a passion for connecting science and communities. She founded Sci4NY - Science for New York - with the goal of spreading young scientists’ appreciation for, and trust in, community political and decisionmaking ecosystems by participating in them. This essay she wrote for the organization Engineers and Scientists Acting Locally (ESAL), is a great introduction: Tips for Scientists to Work Effectively with Communities.

I find this kind of task is best learned as a real-life experiment where one ventures out as a “student of the community.” Taking a proverbial random walk, as well as a physical stroll from time to time, can provide a sense of the issue’s landscape. In this process:

Talk to people that live or work in the community, play a role on local boards, are engaged with nonprofits, etc.

Pay attention to how the community is organized. This includes where and when public meetings take place. Attend as many as possible.

Do read the rest!

And then there’s ESAL itself. They have a playbook for local engagement and lots more resources just waiting for engineers or scientists to find their place in, and build trust with, local communities and decisionmakers.

The deeper challenge

There are deep issues driving the decline in public trust in science and understanding of how science helps us all navigate each day. The pandemic created a particularly dramatic downward jolt.

, a longtime expert studying the interface between science and policy, has posted an excerpt from a new American Enterprise Institute essay on “The Politicization of Expertise, that gets at longer-term challenges and choices.Cutting to the chase, here’s his closing call to action:

In 2025, addressing the crisis of confidence in public trust in science should be the credential-expert community’s top priority. It is that important.

And here are his three core points:

First, leaders in the credentialed expert community—college presidents, presidents of scientific organizations, and public intellectuals—need to be much more vocal in expressing that academic and scientific institutions serve all of the public, not just those who happen to share the values and orientation held by most academics and scientists. Leaders need also to push back vigorously against those in academia and science institutions who seek to use those institutions to wage political war with their fellow citizens.

Second, politicians and the media should stop using science and scientists as convenient political wedge issues for partisan gain. A good example is the debate over COVID-19 origins, which was immediately politicized in partisan terms, creating obstacles to an expert-led investigation of the world’s worst pandemic in a century. Remarkably, we still do not know the origin with certainty, although the picture is slowly becoming clearer.

Third, credentialed experts need to make peace with democracy. Neither science nor academia is a political party or part of a political party. In many ways, expertise is a public good—the incredible successes of democracy in America have resulted in no small part due to our history of following Schattschneider’s maxim. So we must have a pragmatic division of responsibilities that integrates unique expertise and unavoidable ignorance in service of our common interests.

Scientists and the institutions they lead probably cannot do much to arrest the overall decline in public support for institutions, but it is well within our scope and responsibility to address the current partisan, educational, religious, economic, and racial divides in how credentialed experts, academics, and science are trusted among the broader public.

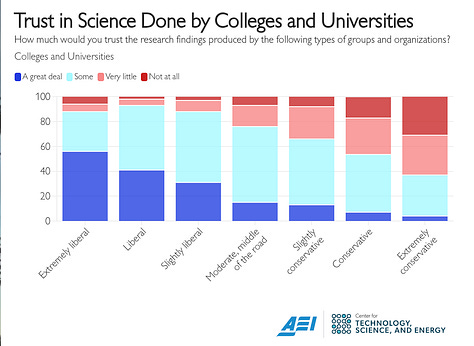

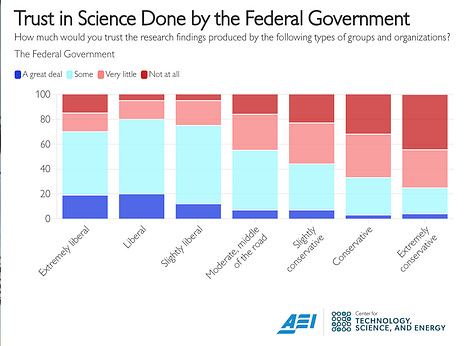

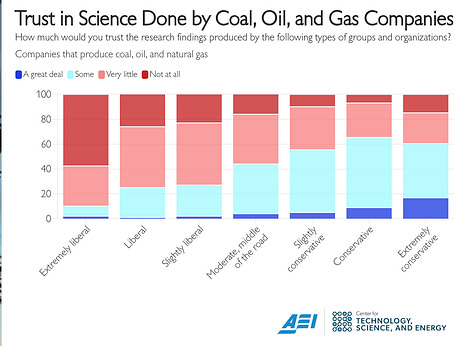

The AEI has done some useful surveys on trust in science. Here are a couple of graphics from a report here.

Here’s a relevant Sustain What webcast: