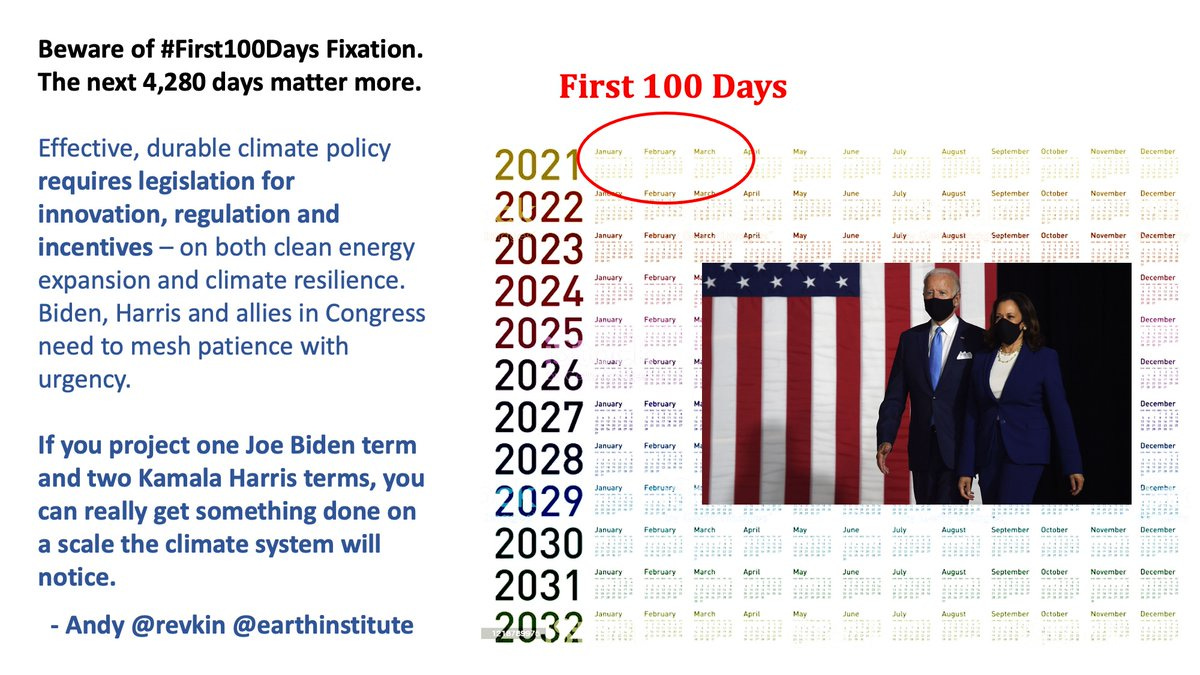

The last time I wrote for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was shortly before President-elect Joe Biden took office, January 12, 2021. In my article, To build climate progress on time scales that matter, Biden should be Biden, I focused on why the "first 100 days" mania at the time was a distraction from the need for a long game on climate action - one that could extend through at least two or three terms.

I created the visual below to encapsulate the themes in that essay. It holds up pretty well!

The only way to play the long game, I wrote, was this:

The urgent task for Biden now is prioritizing and navigating among competing constituencies—and amidst America’s divided politics—with sustained climate progress in mind.

As events in 2022 and onward conspired against climate action - from Putin’s war to inflation to unrelenting Republican obstruction - I made this illustration:

But the Biden administration, with a delicate and sometimes fractious coalition in Congress and beyond, navigated through the storms.

The first foundation stones of an enduring American climate shift were laid with the remarkable Biden-administration successes of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, CHIPS and Science Act and Inflation Reduction Act.

And now here we are, about to see if it’s possible to sustain that long game in the United States through the election of Kamala Harris.

Here’s my new Bulletin essay:

Why this is a climate election—even if that hasn’t been apparent on the trail

(Reposted from The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

There’s been a deep disconnect for decades between the scale of the threat scientists say is posed by unabated human-driven global warming and the response of politicians. And that’s never been clearer than in the 2024 United States presidential race.

Last May, the Washington Post revealed former President Donald J. Trump was hoping to swap reversals of climate regulations for a billion dollars in oil-industry campaign donations. The threat of a profound White House policy reversal under a possible second Trump term was building even as global temperatures hit new record highs, deadly deluges were regularly making headlines worldwide (all the way up until the week before the election), and new studies increasingly showed the climate-treaty goals set in 2015 were inching further out of reach.

Despite all those flashing warning signs, this has been anything but a climate election—on the surface—given the brimming basket of economic and social issues topping voter concerns, and thus party platforms.

Those real-time worries are a big reason why, when climate and energy came up in the debates or other forums, while Trump proclaimed his love for “liquid gold” (oil) and fracking, both President Joe Biden and his successor on the ticket, Vice President Kamala Harris, would pivot from quick acknowledgments of the momentous climate threat to stressing record high production of oil and gas to cut consumer costs.

In the end, the contortions required to knit electoral-college victory paths always make campaigns a lousy barometer of what presidents can and will do in office.

In fact, this is absolutely a climate election where it matters most: in policies, budgets, and basic principles.

Trump’s disdain for actions addressing global warming is clear, along with his determination to exact retribution by reversing, “on day one,” the energy-and-climate-related executive orders of President Biden.

His Agenda 47 website does have a section on expanding nuclear energy, including streamlining Nuclear Regulatory Commission rules hindering the flow of new plant designs. But on the Joe Rogan show on October 25, he expressed concern about nuclear plant costs and risks: “They get too big, and too complex and too expensive…. I think there’s a little danger in nuclear.” Even on this climate-energy policy, he weaves wildly.

It’s hard to reconcile Trump’s platform stance on nuclear with his attacks on the Biden administration’s landmark Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). As James Pethokoukis of the free-market-oriented American Enterprise Institute recently wrote, “Trump’s vote for nuclear energy abundance seems to conflict with his distaste for the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—despite the considerable IRA funding going to red states—which includes substantial nuclear power incentives.”

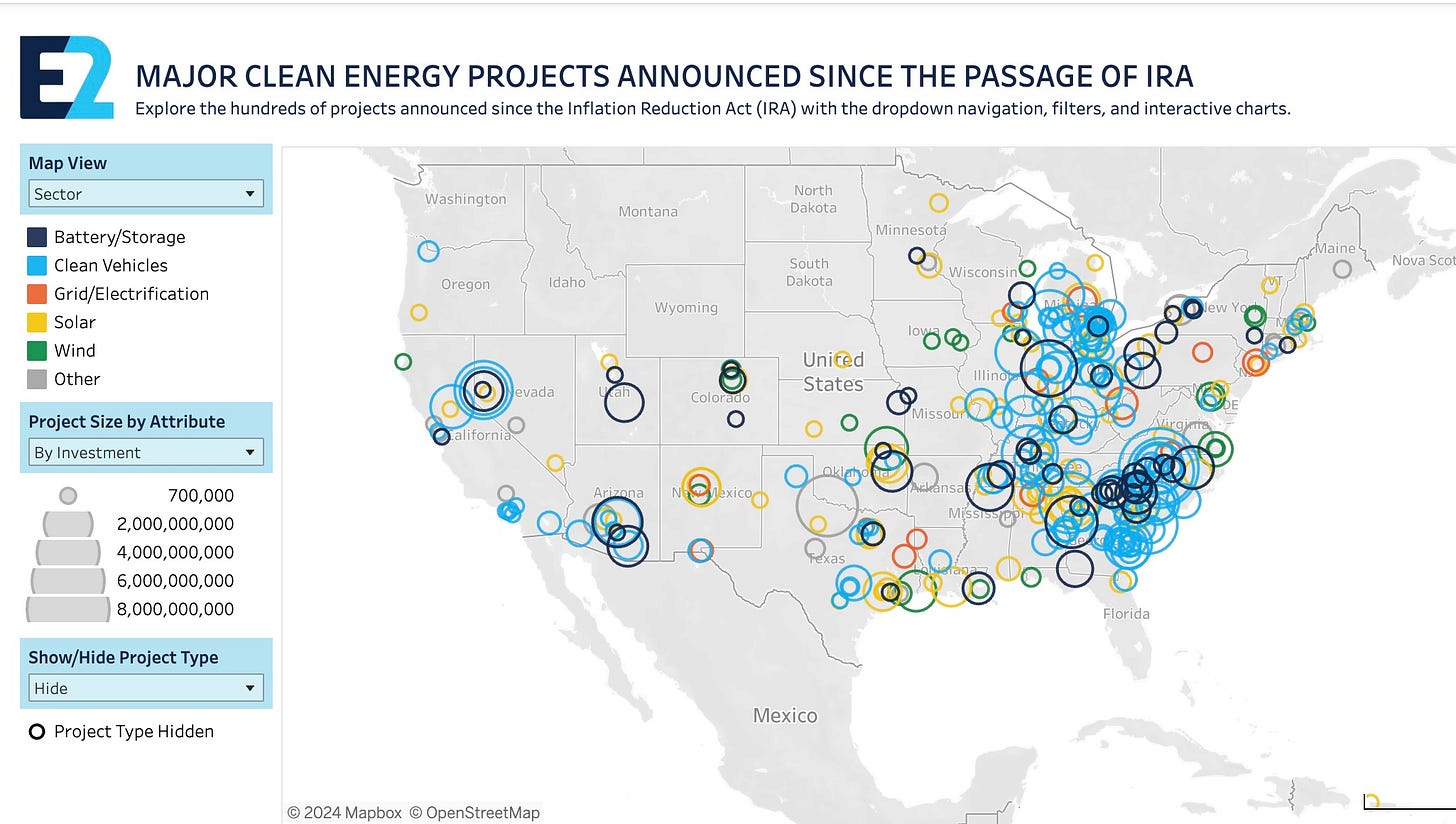

A nonpartisan organization, E2, found in August that, two years in, “more than half of all [IRA] projects were in Republican districts, and 19 of the top 20 congressional districts for clean energy investments are held by Republicans.” You can explore these in more detail in an online map.

While you might argue that, well, the world didn’t end in Trump’s first term, there’s abundant evidence that it was, in essence, just a practice run, inadequately reflecting what he could do starting on January 20, as a couple of his top environmental appointees told CNN’s Ella Nilsen last July:

“‘We lost a fair amount of time early in the Trump administration because we weren’t as prepared as we would be for round two,’ Mandy Gunasekara, former chief of staff of the Environmental Protection Agency under Trump, told CNN. The lesson learned, she said, is to move with speed. Trump’s circle of influence is more organized this time, focused on gutting key agencies that oversee environmental protection and unwinding most, if not all, of Biden’s marquee climate rules. It could happen ‘very fast,’ said David Bernhardt, who served as Interior Secretary in the Trump administration.”

Both Gunasekara and Bernhardt contributed to the conservative Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 template for a second Trump term. Although the former president has disavowed the plan on the campaign trail, the architects are deeply connected to his team, and the stated goals of the plan dovetail with Trump’s zeal for gutting agency budgets and regulatory power.

In profound contrast, a Kamala Harris administration would be positioned from day one to build on Biden administration moves over the last four years, in particular the hundreds of billions of dollars in clean-energy investments flowing under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the IRA (for which Harris cast the tie-breaking vote).

Of course, Harris’s campaign statements touting oil and gas abundance and her retreat from a 2019 presidential primary statement supporting a ban on fracking have infuriated some of the most liberal voters, as has the administration’s record on Gaza.

But in recent weeks, many climate-focused progressives, including Bill McKibben and New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, have pressed for such voters not to sit out the race or vote for a third-party candidate like the Green Party’s Jill Stein.

Costa Samaras, a climate and energy researcher at Carnegie-Mellon University who was a White House adviser for the clean-energy transition through 2022 and 2023, said he understands some voters’ frustrations that climate has taken a backseat in the election.

“Every ton of CO2 matters, so we need to be pushing as hard as we can to reduce climate pollution everywhere faster,” Samaras said in an interview. “But I think, overall, the type of pathway that the Biden-Harris administration has laid out will enable the continuation of a decarbonization coalition that gets us to a zero-carbon economy as soon as possible.”

Related posts

Rev. Lennox Yearwood Jr. and

on the Climate Voters for Harris-Walz Substack:

The long game is to get to taxation of net CO2 emissions. Everything else should be thought of as stepping stones and second best approaches. Some anti-CO2 emissions policies such as blocking specific US fossil fuel production nd transportation projects can be so costly as to actually be counterproductive.

Andy Understand your plea for funs, but I am in England and our Pensions have just been gutted by a LABOUR Government. For me it's heat or eat. Sorry