The Deeper Meaning of Ice Age Fossil Footprints in New Mexico's White Sands

Knowledge of the human journey so far remains a work in progress.

Update, 5 October, 2023 - An extraordinary, and hotly contested 2021 research finding, that human footprints in a New Mexico national park dated from the depths of the last Ice Age, has been reinforced through several additional lines of evidence.

The new study, published in Science, concludes that “the chronologic framework originally established for the White Sands footprints is robust and reaffirm that humans were present in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum.” There’s lots of news coverage of course, including a really well done New York Times story by Maya Weis-Haas. There was a lot of resistance from other scientists to this and other data points showing humans were sweeping across North America way earlier than longstanding hypotheses. But the old narrative is eroding fast.

The wider issue, which I explored below when the first paper broke, is almhost as important as the core finding. It’s about the need to remain open to new ideas when long-established narratives are challenged by evidence-based analysis. Beware what I call “narrative capture.” There are no slam dunks, of course, and it’s equally vital to look at new paradigms with skepticism.

Please have a look back. This was written well before my move to Substack.

Original post - The new 23,000-year age estimated for fossilized human footprints crisscrossing sites in White Sands National Park in New Mexico provides yet more sobering evidence that it's best to think of textbooks, and history itself, as a series of crude, ephemeral tokens, not a firm reference.

If confirmed, the age, putting footsteps in mud as the last ice age was going strong, establishes humans on this landscape many thousands of years earlier than long-prevailing estimates for North American human habitation. It was derived by a research team using carbon dating of grass seeds in ancient layers of soil between those marked by human and animal feet. The study, published Thursday in the journal Science, has a remarkably clear abstract:

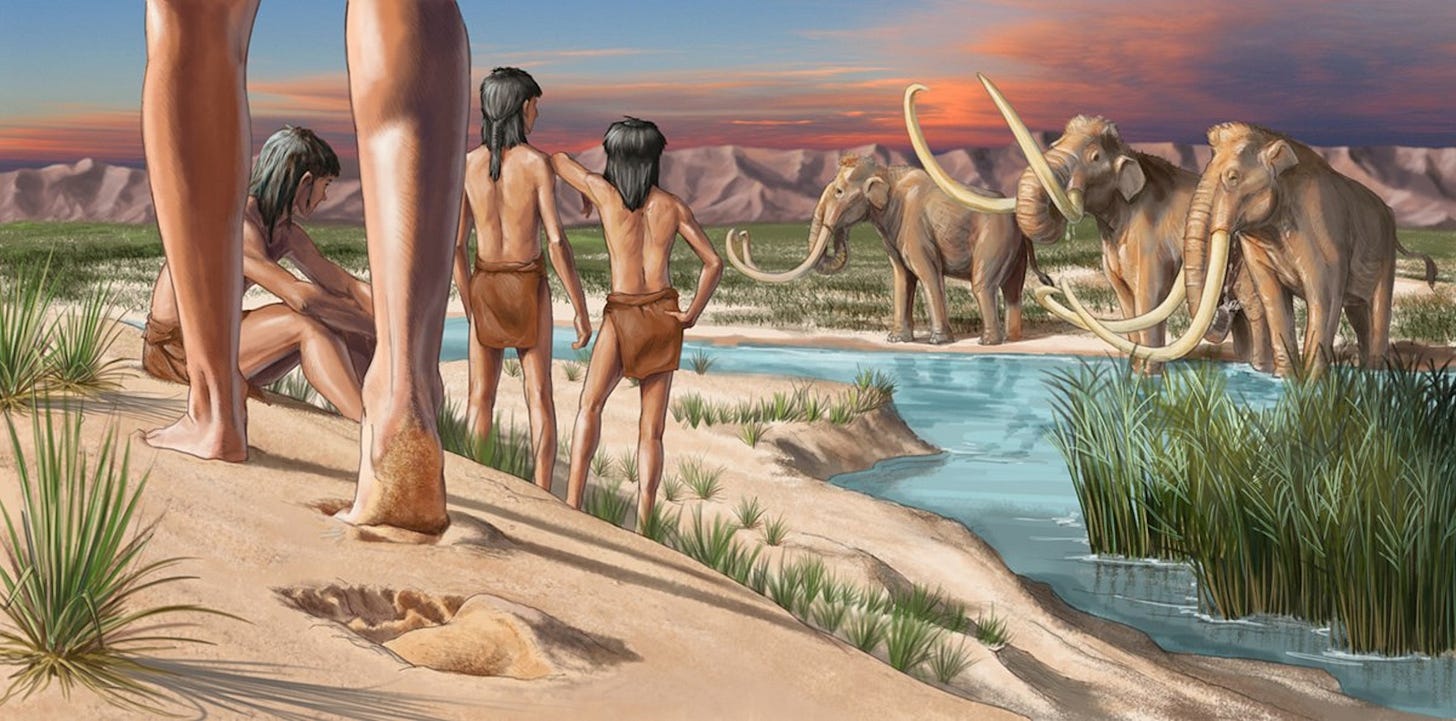

Archaeologists and researchers in allied fields have long sought to understand human colonization of North America. Questions remain about when and how people migrated, where they originated, and how their arrival affected the established fauna and landscape. Here, we present evidence from excavated surfaces in White Sands National Park (New Mexico, United States), where multiple in situ human footprints are stratigraphically constrained and bracketed by seed layers that yield calibrated radiocarbon ages between ~23 and 21 thousand years ago. These findings confirm the presence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum, adding evidence to the antiquity of human colonization of the Americas and providing a temporal range extension for the coexistence of early inhabitants and Pleistocene megafauna.

There's a ton of great reporting on this. In particular, read Carl Zimmer's fine New York Times story. He describes the tussle among various camps in archeology and related fields and even among those seeing different paths for the earliest colonizers of North America - one a coastal route skirting the vast ice sheets, another inland path proposed potentially 32,000 years back in time.

The new research has a host of cultural interpretations, as well. For her story in the news section of Science, Lizzie Wade reached out to a Native American community. She writes:

Kim Charlie, an enrolled member of the Pueblo of Acoma in New Mexico, feels a deep connection. “Thousands and thousands of years ago, our ancestors walked this place,” says Charlie, who has visited the footprints and even uncovered some herself. Seeing prints of humans together with extinct megafauna such as camels sheds light on why the Acoma language has a word for “camel,” she says.

In all of the news coverage, other researchers are acknowledging this new work's strength, but - as always - calling for parallel lines of evidence or confirming analysis before a new chapter is written in the ever-evolving book charting humanity's long journey.

But it's becoming ever clearer that the Americas were home to humans far longer than we long imagined.

Let’s Revive the "American Tentative Society"

As I expressed in my opening line, this discovery is important for our understanding of intermingled human and environmental history, but also as a reminder of the value in avoiding what I've called "narrative capture" - getting seduced by a story line.

So many parts of human history are taken for granted, either because victors wrote the books (where was the Tulsa Massacre when I was a kid?) or evidence is simply glaringly absent. As I've said before, a paucity of evidence breeds an overabundance of assertion. Queue the wild debate about an asteroid explosion taking out Sodom.

Compelling but faulty narratives are hard to kill. This can happen in every field and on any issue. Remember that Barry J. Marshall and J. Robin Warren, the Australian researchers who discovered the bacterial source of stomach ulcers, were attacked relentlessly - until their work was finally established and they received the Nobel Prize for medicine in 2005.

Like all of us, I fail sometimes. I've been captured by narratives as a journalist.

But I do try hard to avoid this trap - not for self protection but because I've learned through experience that "cultural cognition" (filtering realities through our relationships and affiliations) is a real issue.

I've long loved how an informal organization of veteran journalists called the American Tentative Society conveyed the value of constructive skepticism way back in 1974:

"There is a hazard when we learn anything…. We may become prisoners of our own dogma.. arrogant in defense of some outmoded ‘truth.’"

The mission of two Tentative Society founders, Rennie Taylor and Alton Blakeslee, longtime Associated Press science journalists, is happily being sustained through graduate-study fellowships for science writers and students offered by the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing.

Sadly we're surrounded by instances in which a compelling narrative lives on way past its expiration date. One other example is Jared Diamond's bestselling and enduring explanation for the "collapse" of the society that built Easter Island's astounding monuments. Over the last two decades, his argument has eroded to the point of collapse. Read Keith Kloor and Mark Lynas, particularly.

But the vision lives on, like the statues.

Fifteen moʻai heads at Ahu Tongariki on Easter Island (Photo by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Your turn

Where have you seen this pattern?

Where are we insufficiently tentative, and what's the risk in that (or the opposite)?

Please join the conversation in comments below.

Visual

Here's a warning sign to share and post whenever you feel #narrativecapture is in the room.

Postscript

My Bulletin colleague Antonio Mora has written a fun muse examining the revelations about these ancient footprints in the context of simultaneous publication of historical hints that "sailors in Christopher Columbus’ hometown of Genoa knew of America’s existence 150 years before its 1492 'discovery.'" I hope you'll subscribe to Mora's dispatches

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues.

“ Seeing prints of humans together with extinct megafauna such as camels sheds light on why the Acoma language has a word for “camel,” she says”

How would someone whose ancestors had not seen a camel for tens of thousands of years know they had a word for camel? How would they communicate this? Is this story narrative capture?