Study Boosts Tree Species Count to 73,000 and Finds Hot Spots Where 9,000 More Species Await Discovery - if Forests Are Conserved

Subscribe to receive my Sustain What dispatches by email.

I first fully absorbed the extent of human ignorance about the wonders hidden in the great forests of this world in 1989, while trying to keep up with Doug Daly, an American botanist following a Brazilian rubber-tree tapping guide along a flower- and leaf-strewn path in Acre, the westernmost Brazilian state in the vast Amazon River basin.

Daly, from the New York Botanical Garden, had already been studying the rain forests in this region for more than a decade, but stressed we were surrounded by unknowns. As I later wrote in my book The Burning Season, "Soon Daly had the familiar experience of coming upon a tree that he could not even place in a family, let alone a genus or species."

He had to strap steel tree-climbing irons onto his calves and clamber 50 feet up the trunk into the ant- and wasp-filled canopy to snip and drop a branch with telltale fruit. Much later at a lab, he narrowed the tree down to the genus Lanunaria within the Quiinaceae family. (You may have heard of the quince fruit.)

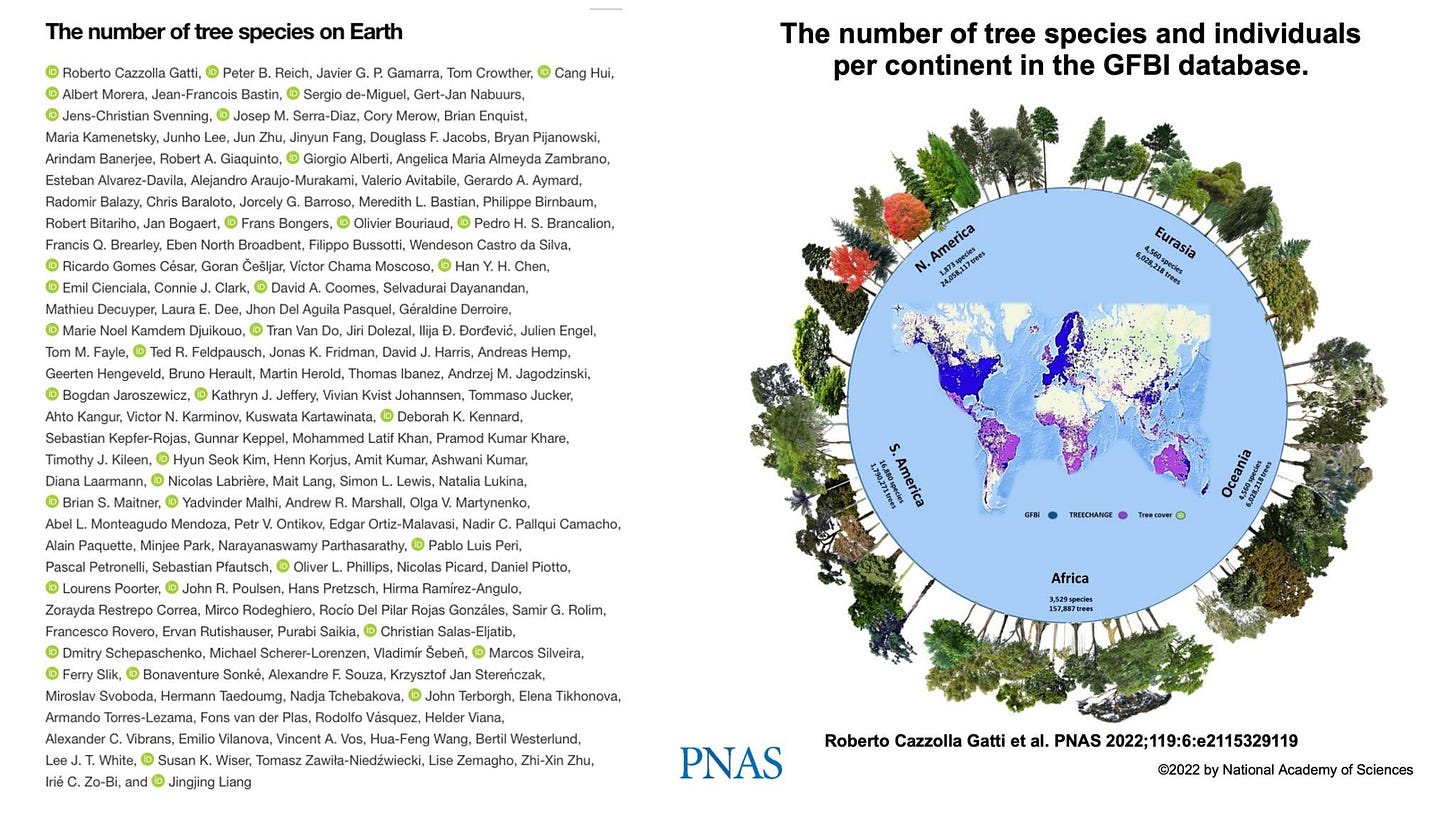

Now a globe-spanning team of scientists, sifting data from 44 million trees on thousands of forest plots around the world - each probed the way Daly did his work long ago - has put forward fresh estimates of known, rare, and as-yet-undiscovered tree types. Key findings include:

The total number of tree species on the planet is now estimated at around 73,000, 14 percent more than had been previously estimated.

The new estimate means there are some 9,000 tree species out there still waiting to be discovered.

South America is a hot spot for both rare species and overall tree diversity.

The study is published in this week's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences under a deceptively simple title: "The number of tree species on Earth." But the statistical methods and volumes of data were so daunting that they required the computing power of Purdue University’s Lab of Forest Advanced Computing and Artificial Intelligence.

The project drew on massive data sets of the Global Forest Biodiversity Initiative and TreeChange.

There's much to explore about the research in Vice, the Guardian and on the website of Purdue. This video provides a valuable visual overview:

I sense one of the greatest values of this work is that it can help countries prioritize conservation efforts and pinpoint places where a new generation of biological explorers like Daly (hopefully from the regions harboring this biological richness) can focus to fill the knowledge gaps projected by the researchers' algorithms.

A mountainous tree exploration hot spot

As I read the estimate of 9,000-plus species yet to be found, I immediately thought back to the work and dreams of the great biologist Edward O. Wilson, whose death at age 92 was marked here in December.

Wilson did pathbreaking research on an array of fronts, from social science to conservation. But his eyes lit up most when he talked about species discovery.

He would have been thrilled with the precision with which this new analysis identifies spots to explore as well as protect - for example the forests on the flanks of the Andes in South America above elevations of 1000 meters.

Here's a portion of my 2019 interview with Wilson on species discovery that hasn't been published before (the interview was for this profile I wrote for National Geographic):

"We don't know enough about ecosystems. We should be choosing them according to the number of species that are in each. And particularly the number of endangered species of some kind. And in order to do that, we should take a big step forward in mapping the species of plants and animals and microorganisms on earth.

"I call it the Linnaean renaissance. That is to say we're taking up where Linnaeus began in 1735. His desire, his goal, was to find and name all of the species of organisms on Earth. He figured there might be 20,000 or so and he set out to do it, and give each one a Latinized name, a scientific name. Now we're saying it's really up there as high as 10 million, most of which are still undiscovered. And that we should above all things start finding out what they are and where they are. And as we do so, we can find particular areas that have large numbers of endangered species in them.

"They may have one eco-region, small eco-region in them, or two or three. But eco-regions are a subjective decision made with inadequate knowledge of biodiversity. If we can map the species as we are now, …we can make the right decisions for the long term, protecting the largest number of species that are endangered to some degree, or may come into endangerment.

"I see this as the single biggest goal of ecology of the future, and…it's going to provide an exciting realm of investigations ongoing that include a lot of old-fashioned exploration, long trips into unknown areas, and the discovery of remarkable new species."

Valuing forests not just for utility

Most assays and analyses of forest dynamics you see are premised on utility - the biological diversity as a font of future drugs; trees measured as tons of carbon; the soil and root systems as a sponge constraining floodwaters or preventing landslides; the wood of course a source of materials.

But there is merit in understanding these astonishing ecosystems to help conserve them for their own sake. That's why I reached out for a reaction to the study from Irene O'Garden, a poet, essayist and educator who, in the days before the pandemic, would dress as, yes, Mother Nature and lead groups of children on walks in the woods in New York's Hudson River Valley and ask each child, "Tell me how the forest might answer the question: 'Forest, what would you like?'"

O'Garden, who published a book of answers with that title, replied:

"Over 73,000 species of trees? What joy. This is a tremendous number, representing not only the fantastic diversity and inventiveness of these remarkable Earth companions, but also the massive cooperative network of people who coordinated and carried out the count. We are deeply enriched by this knowledge, heartened by the international effort that made it possible and prompted to do even more to preserve the gifts of our planet."

Here's to all of the researchers who contributed to this epic work, including the legions of botanists who got stung, scraped and sweaty turning tree measurements and samples into data.

Help build Sustain What

Thanks for commenting below.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues!