September 11 Then, Now and Ahead

A reflection on lessons learned and as-yet unlearned after an epic rupture that has yet to heal

This repost from my pre-Substack days is worth recirculating. Where were you, what implications and impressions linger?

On that sparkling, unremarkable Tuesday morning in 2001, I was on a train heading into The New York Times from my home in the Hudson Valley.

I was on a later train than usual because there had been traffic along my route after dropping my older son at his school near his mother’s home 15 miles east.

Starting around 9:00 a.m., a quiet chirping of phones built in the crowded rail car. People stiffened. No one had a smartphone with video or the like, so the full scope of what was unfolding was beyond our grasp – so far. But from the murky back and forth muttering a communal sense of comprehension and fear enveloped the train. An announcement squawked about a falling tower.

The picture sharpened as the morning unfolded, one horror after another. One World Trade Center, known as the North Tower, had been hit at 8:46 a.m. Eastern time and collapsed at 10:28. Its mate, Two World Trade Center, was hit at 9:03 a.m. and collapsed at 9:59 a.m. Columbia University seismologists recorded the terrestrial vibrations with chilling precision.

To the south, the Pentagon had been struck at 9:45. To the west, around that same moment, passengers and flight attendants on hijacked United Airlines Flight 93 out of Newark, in an act of astonishing bravery, breached the cockpit and that jet rolled and plunged into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, at 10:10. I still haven’t had the courage to watch the film "United 93."

As a reporter at The Times, when the trains shut down for good, I felt helpless and frustrated that I wasn’t in the city to help my colleagues fan out and make sense of the unfolding events. Those at Ground Zero were, and remain, heroes.

As a father and husband, I was determined to retrieve our toddler son from his daycare center in Peekskill, a town between where my train had stopped and our home. My wife was teaching at a private school an hour away (where, it would emerge, several students had lost parents in the attack).

I found a taxi and headed upriver to pick up my car from the gas station where it was poised to be serviced. My first stop was the Flying Goose daycare center. It was nap time when I arrived. Rather than rouse Jack, I switched to reporter mode and drove to the Indian Point nuclear power plant complex a few minutes away.

At least one of the airliners hijacked in Boston had flown down the Hudson Valley directly overhead at one point. What was being done to secure the facility if more threats followed? I sent in my take to the desk, noting heavy trucks had been pulled across the entrance. Slim comfort. (It would later be discovered that Osama Bin Laden had considered nuclear plant targets.)

Then I picked up Jack and headed home to continue reporting on bits and pieces of the unfolding transformation of our world.

In the first hours, like hundreds of colleagues in New York and around the world, I was simply scouring my sources by phone and email nonstop for any facts or observations or contexts that could fill gaps in the overall Times report, which eventually evolved into a multi-year package called “A Nation Challenged."

That rubric could still apply to this country, given how the repercussions of the surprise attack, and America's response, have played out decade by decade.

Here are a few story lines I dug in on, and a few related reflections. I hope you’ll take time to offer your thoughts in the comment stream below.

Cadets confront a new kind of war

My first standalone story was on the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, directly across the Hudson from my town. I headed through rings of hastily deployed extra security to learn how the faculty and the first cadet class of the new millennium were dealing with this rupture to all the norms that had built that school of war since its founding in 1802.

This story, published that first Saturday, September 15, captured themes that still simmer: “New Enemy Challenges the Academy's Old Curriculum.”

Ponder recent debates about the meaning of the 20-year war in Afghanistan and our other post-9/11 interventions in the Middle East as you read this excerpt:

In her political and cultural anthropology class, Maj. Sonya L. Finley showed cadets slides of the carnage and described how their commander in chief, who was visiting the ruined World Trade Center today, had called for a protracted campaign to wipe out terror.

''How do you fight this war and still stay true to the values of the United States?'' she asked her seven-cadet class, six seniors and a junior seated in a tight circle. ''Any ideas?''

There was a long initial silence before the cadets began to feel their way into their future.

''Our army isn't organized to fight this kind of battle,'' said Robert Decker Jr., from St. Petersburg, Fla. ''This isn't tanks rolling across the desert.''

Then Finley displayed a graph she’d borrowed from another professor, who had drawn it the day after the attacks. It had a downward-curving line labeled liberty and a rising line labeled security. She asked the students the impossible question: what’s the right balance?

Another excerpt:

''We were here,'' she said, pointing to the side where individual freedoms dominated. ''George Orwell's '1984' is here,'' she added, pointing to the opposite side. ''Where are we after Tuesday?''

Where are we now, you might ask.

(Read fellow Bulletin writer Ian Bremmer for one perspective.)

Loss beyond pain

Ten days later, The Times ran my one contribution to the Changed Lives feature, a series of dozens of short articles focused on how the catastrophe was transforming people in all walks of life. I interviewed the folk bard and songwriting pied piper Jack Hardy, someone I’d come to know as my own songwriting sideline brought me to his weekly Greenwich Village “Fast Folk” song-swapping spaghetti suppers.

Hardy had watched the buildings disintegrate knowing he was watching the death of his brother, Jeff, who cooked breakfasts and lunches for the traders at Cantor Fitzgerald, the bond house occupying three floors near the top of the north tower.

Hardy had been muted by the horror until now, but let loose. Not everything he said made it into the resulting story: “A Folk-Song Writer Is Stilled by Discordant Grief.”

An editor cut a line I thought should have stayed, in which Hardy said this: “We raised two middle fingers to the world and filled then with bankers. What did we expect?”

The news process has filters. I understand why it was cut. I think it should have stayed.

Hardy died a decade later of lung cancer, but his sharp-witted work lives on. I think you’ll appreciate his song “Worst President Ever,” aimed at George W. Bush. I still wonder what he would have sung about Donald Trump.

Dust, spores and dread

A view of the debris field (photo by James Tourtellotte, U.S. Customs & Border Protection)

In the ensuing weeks, I wrote extensively about the smoke and dust from the collapsed towers and took heat for sticking with the data, rather than jumping to conclusions about cancer that other media ran with aggressively.

I stand by my coverage, which noted that the deepest health risk lay with those working tirelessly day after day on “the pile” and that people exposed in passing on that fateful day, or who lived downtown, had far fewer reasons for concern. The journalist Susan Q. Stranahan did a deep dive in 2003 assessing coverage of 9/11 health questions for American Journalism Review. It’s worth re-reading now.

As the Associated Press just reported, 20 years later, there isn't much evidence in the wider exposed population of a significant health impact:

Nearly 24,000 people exposed to trade center dust have gotten cancer, but for the most part it has been at rates in line with the general public. Rates of a few specific types of cancer have been found to be modestly elevated, but researchers say that could be due to more cases being caught in medical monitoring programs…. One study showed that cancer mortality rates have actually been lower among city firefighters and paramedics exposed to Trade Center dust than for most Americans, possibly because frequent medical screenings.

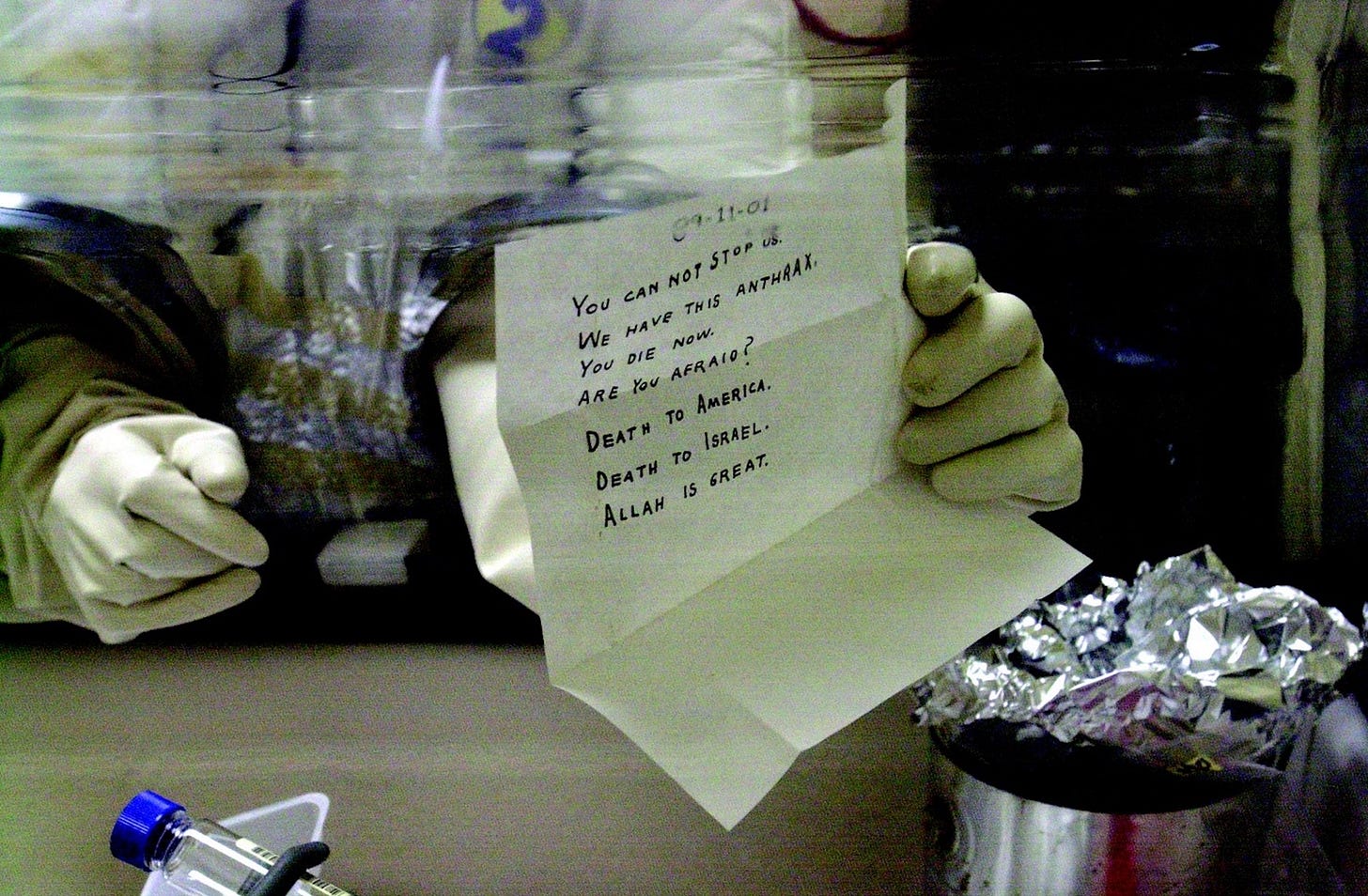

A technician opened the anthrax-laced letter addressed to Senator Patrick Leahy at the U.S. Army's Fort Detrick biomedical research laboratory in November 2001 (FBI)

I was part of The Times team probing the anthrax attacks aimed at media figures, elected officials and others, carried out through the postal service starting a week after the airplane attacks. Five people were killed and 17 sickened. The Bush administration pressed hard to link the anthrax attacks to Iraq, including by feeding the media tips that favored that theory. But the Science desk at The Times, particularly, worked hard to follow the evidence.

As you likely know, the investigation of that appalling crime led to wrongful accusations at first, and then the suicide of a domestic suspect before charges could be filed. Significant questions remain unanswered.

For more on the toxic legacy of 9/11 smoke and dust and the pall of fear that spread from the anthrax attacks, please read the new Foreign Policy column by the Pulitzer-winning health-focused journalist Laurie Garrett. She dug deep from day one and has never flagged.

I explored new possible methods terrorists might use to get around our homeland defenses, particularly truck bombs, drawing on unnerving reporting I had already done on dangers posed by fuel-laden tanker trucks. I developed a bad habit that still kicks in once in awhile, envisioning how attackers might seek mass casualties as I walk down a city street, visit a mall, or marvel at the size of modern cruise ships.

I reported on new detection technologies and weapons deployed (fruitlessly at the time) to find Osama Bin Laden. Think of how weaponry innovation has evolved since - drones for instance.

Climate contexts emerged. I wrote about a study of climate insights gleaned as contrails vanished from the sky when U.S. aviation shut down after the attacks. This animation of the emptied skies is haunting, and feels familiar recalling how the pandemic, in a very different way, stilled aviation.

Late in 2001, I wrote about the extreme drought affecting Afghanistan and the surrounding region, examining how water insecurity can create fertile conditions for instability and extremism.

As the United States pulled out of Afghanistan last month, I invited two of my sources for that 2001 story to join a Sustain What discussion of fragile states, security and climate change. I hope you’ll watch here: Can the U.S. Go From Responding to Fragility to Spreading Resilience?

This section of the 2001 story all-too-neatly describes the climatic and hydrologic challenges that continue to destabilize the region even now:

When the war ends, political tensions are bound to rise as Afghanistan rebuilds its northern provinces and begins drawing more water out of the Amu Darya, which forms part of its borders with three former Soviet republics -- Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The river is already taxed to the limit, with every drop of its annual flow of 19 cubic miles of water -- nearly four times the flow of the Colorado -- siphoned by irrigation and for water supplies before reaching the shriveled Aral Sea.

''In this region, water is more important than money,'' said Dr. Michael H. Glantz, a senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo., who has studied the Amu Darya.

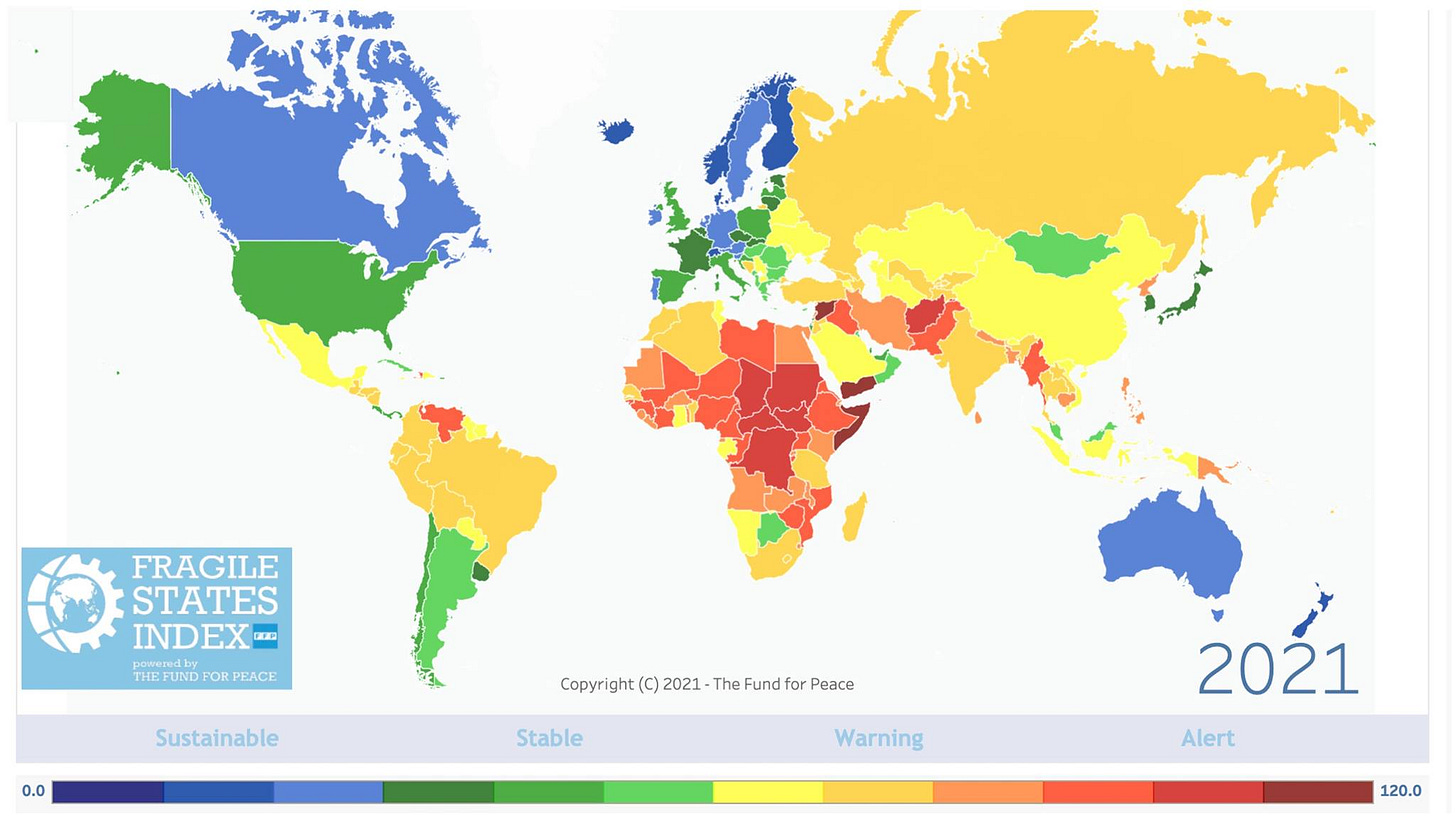

The new conversation with Glantz and others centered on ways to shrink the list of fragile states maintained by the Fund for Peace and partners. Explore the 2021 Fragile States Index. Needless to say, the red in this world map is not sustainable.

fragilestatesindex.org/

In closing, I grieve for those who perished, honor those who served on the front lines at the terror sites and in military and other positions in the following years. I hope for the best possible path forward for those injured physically, psychologically or in other ways on that fateful day and in the years that followed.

Here’s a parting photograph I shot at the World Trade Center Memorial on September 10, 2019.

Thanks for weighing below or on Facebook.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues.