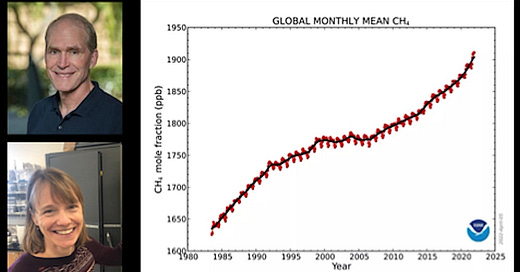

This was a particularly helpful Sustain What show exploring the spike, pause and new surge in emissions of methane, the second most important climate-heating greenhouse gas. Watch and share fresh insights.

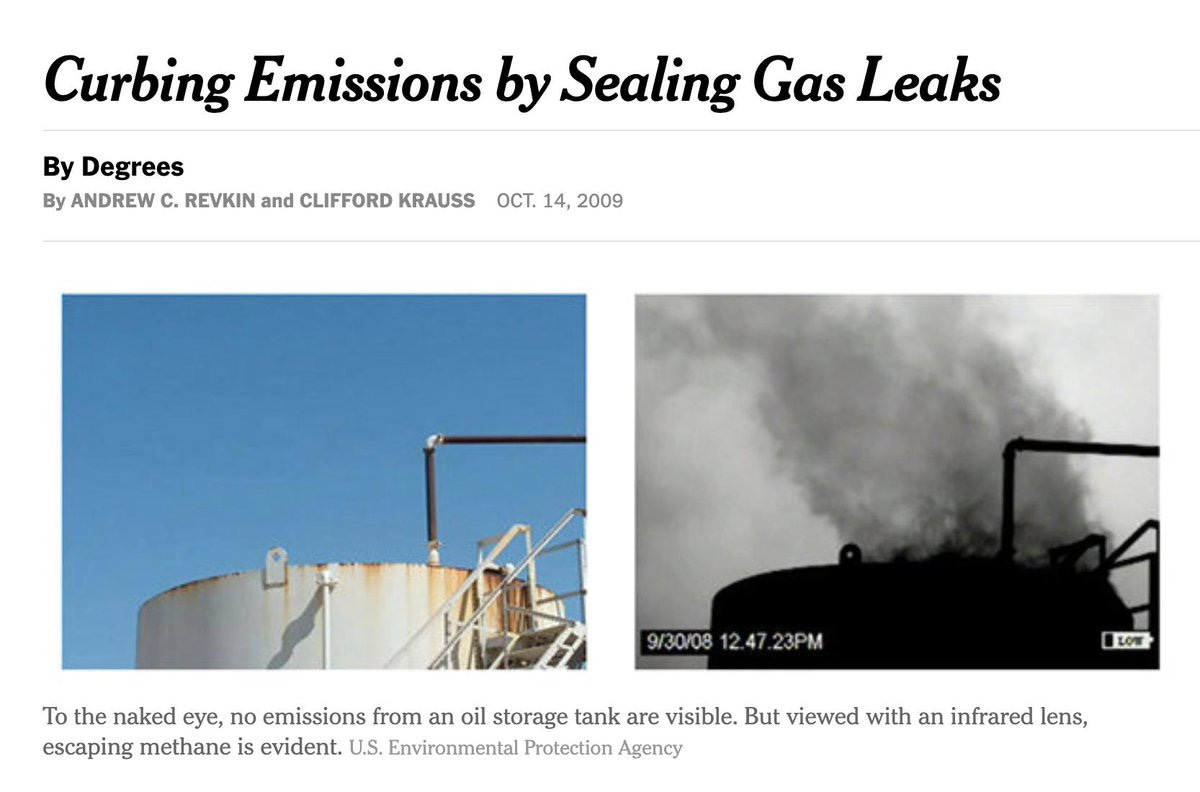

In recent years, I and other journalists have mainly paid attention to emissions of methane from natural gas, oil and coal extraction. It’s sexy and fits political and activist frames. (Remember the fracking fight?) As long ago as 2009, I was reporting on how new technology, particularly infrared imagery (gift link), was revealing methane leak hot spots.

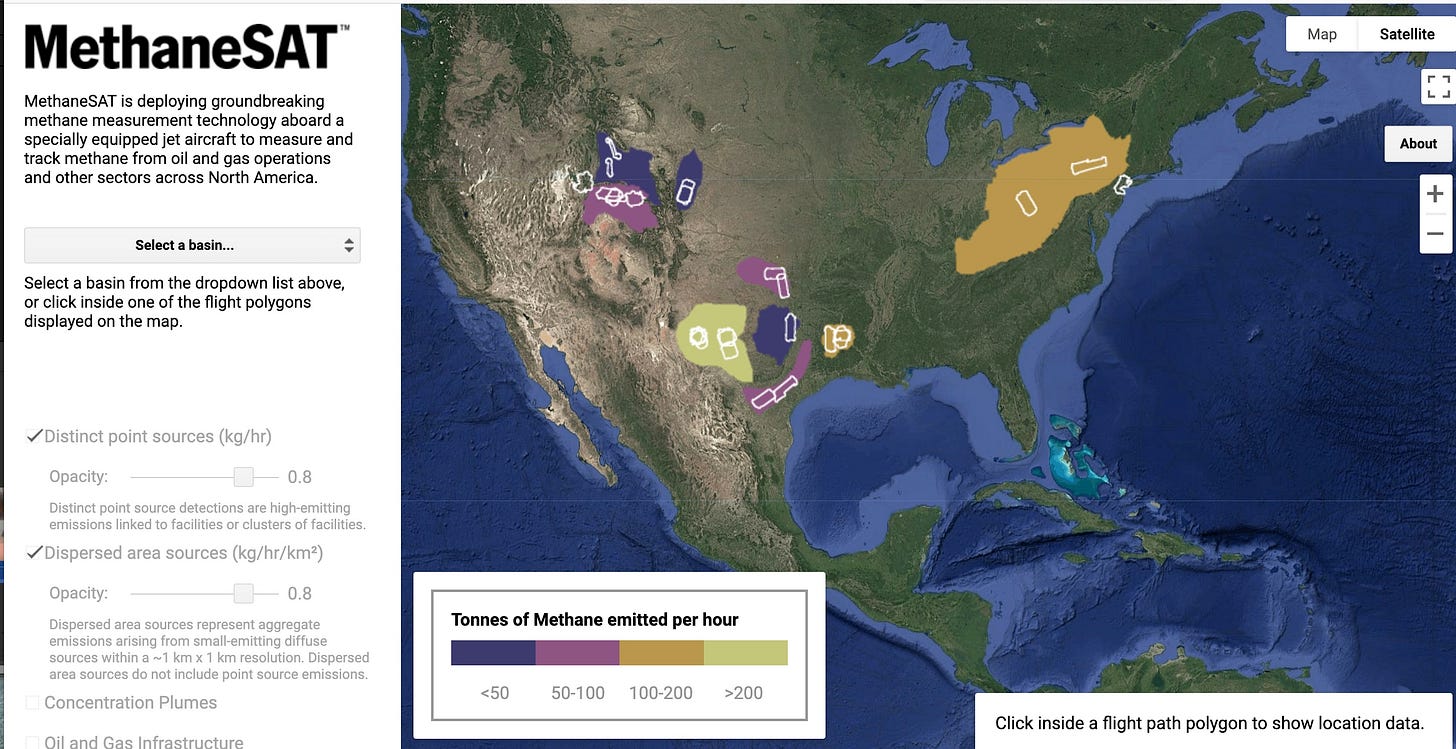

Now satellites are doing this as well. If you’d asked me in 1992, when I did some work with the Environmental Defense Fund, that this environmental group would be launching its own methane-tracking satellite, I would have laughed out loud. And yet..

It’s vital to pursue these no-brainer emission cuts. But it’s grossly insufficient, as you’ll learn.

Media also focused on dramatic instances of methane releases in the Arctic, like combusting puffs of the gas released from warming lakes, as shown here by Katey Walter Anthony of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

But it turns out that the tropics, and particularly wetlands, are the main source of emissions growth in recent years (see this comprehensive 2023 analysis). The Arctic may shift into the plus category down the line, but much-clicked permafrost “methane time bomb” headlines - part of the grander theme of catastrophic climate tipping points - don’t hold up too well, as you’ll learn a week from Friday in a webcast on this new paper: ‘Tipping points’ confuse and can distract from urgent climate action. I’ll post on this event shortly. An earlier tipping point dicussion with one author, Michael Oppenheimer of Princeton, is here.

My guests on December 6 were two top-notch methane researchers, Rob Jackson of Stanford University and the Global Carbon Project, who has a new book on climate solutions, Into the Clear Blue Sky: The Path to Restoring Our Atmosphere; and Sylvia Englund Michel of the University of Colorado, who led a new study pointing to biological sources - not gas and oil produciton - as the main source of the recent buildup.

Here’s the open-access study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: Rapid shift in methane carbon isotopes suggests microbial emissions drove record high atmospheric methane growth in 2020–2022. Michel was also a co-author of the 2023 paper I cite above pointing to the tropics.

You can also watch and share the show on Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube or X/Twitter.

Explore Jackson’s new book, Into the Clear Blue Sky - The Path to Restoring Our Atmosphere.

Here’s an excerpt from a previous Sustain What conversation on the methane side of the climate challenge and a global pledge for deep reductions made as part of the climate-treaty negotiation journey. The full discussion is here.

A deeper methane dive

Heat-trapping carbon dioxide remains the gorilla in the global greenhouse - with its long lifetime once liberated making its heating influence on climate cumulative. It builds like unpaid credit card debt, meaning the pain doesn’t stop just because you cut spending.

If all human-generated emissions somehow stopped, warming would rapidly come to a halt, as

just explored on . But there is zero chance (even net-zero chance) of that happening for decades given global trends in energy demand compared to advances in clean-energy options, infrastructure lock-in (see my energy-transition chat with Mekala Krishnan and the output of ) and the scale and cost of methods for drawing carbon dioxide out of the air and putting it in millenniums-long cold storage (see my epic CCS conversation with Vaclav Smil).Those realities, along with arguments that rapid cooling steps are necessary to forestall imminent tipping-point catastrophic warming (even though many climate scientists say that threat is overstated), have put the spotlight on actions addressing the methane problem.

Methane matters

The CH4 molecule is the main ingredient in what industry calls “natural” gas - with leaks from coal mines and gas and oil infrastructure a major source. It’s also generated through biological processes taking place in the guts of ruminant livestock as well as wetlands around the world - whether natural or human-built (e.g., rice paddies).

Methane has dozens of times more heating influence than CO2 but is broken down within a decade or two, meaning stopping emissions can rapidly stabilize the amount in the air and limit this contribution to planetary heating.

Here’s a deft summary of the situation by the longtime methane analyst Drew Shindell of Duke University (part of a package published in July with a multi-author Frontiers in Science paper laying out a three-pronged strategy for methane stabilization):

[T]he amount of methane in the atmosphere has more than doubled since the Industrial Revolution, with increased methane emissions causing about two-thirds as much warming as CO2 to date [2]. But, on the bright side, methane is naturally cleared from the atmosphere much more quickly than CO2: while CO2 sticks around for centuries, most methane only stays in the atmosphere for about a decade. This means that while reducing CO2 emissions is the most important thing people can do to protect Earth from climate change in the long term, reducing methane is the most important thing we can do to help our climate in the shorter term, to keep the planet as healthy as possible while you and your friends grow up.

Also read this September commentary in The Conversation, by Pep Canadell, Marielle Saunois and our guest, Rob Jackson: Methane emissions are at new highs. It could put us on a dangerous climate path