Putin's Ukraine Escalation Prompts Fresh Urgency on "Nuclear Winter" and U.S. Nuclear Posture

In the Cold War, scientists found fires from a nuclear war could loft so much smoke high into the rainless stratosphere that solar dimming could spawn famine. Lately, the science has strengthened.

Please SUBSCRIBE to receive my posts by email (content always free).

Phrase of the week - "deconfliction hotline"

As Vladimir Putin's horrific war on Ukraine intensifies, there have been flashes of what counts as good news these days.

Late in the week, the Wall Street Journal reported that the Pentagon and Russian counterparts established a "deconfliction hotline," a communication portal, also used around the Syrian conflict, aimed at avoiding spiraling missteps. Such circuit breakers are an essential way to limit odds of accidental escalation - one of the three flavors of war escalation I wrote about earlier this week.

And the fire reported at the largest nuclear power plant in Europe was actually at a training facility outside the plant perimeter, not that this reduces deep concern about Russia's capacity to unleash holy hell in its messy surge into a country with 15 power-plant nuclear reactors and the wreckage of Chernobyl. (Follow James Acton of the nuclear program at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace for more and read his piece on Ukraine's nuclear status.)

President Joe Biden is poised to update the United States Nuclear Posture Review. I hope Putin's aggression doesn't sway the administration to give up on some of Biden's earlier pledges to focus on deterrence and arms reduction. But with the midterms and 2024 in mind, I wouldn't count on this. And history has shown how difficult it is for any president to counter the pull of politics and path dependency and the self-sustaining power of the military-industrial complex. See the readings below for some invaluable guidance.

Nuclear winter is back

The prime focus worldwide has to be on finding ways to counter or slow Putin's unprovoked Ukraine invasion and help the millions of Ukrainians whose lives are imperiled or up-ended.

And it's equally vital to support those in Russia courageously protesting against this war crime. (I hope science organizations are trying to protect Oleg Anisimov, who was threatened with "oblivion" by a Putin crony after he spoke against the invasion at last weekend's meeting approving the latest United Nations climate report.)

But given Putin's evident disregard for any outside influence (at least so far) and given evidence that Russia's war-fighting strategy may have shifted to include nuclear weapons in regional conflicts (see the Congressional Research Service report below), it's also vital to weigh some planet-scale facets of this crisis.

That includes swinging back to an issue I first reported on during the first Cold War: the prospect that even a "limited" use of nuclear weapons could produce a planet-girdling "nuclear winter."

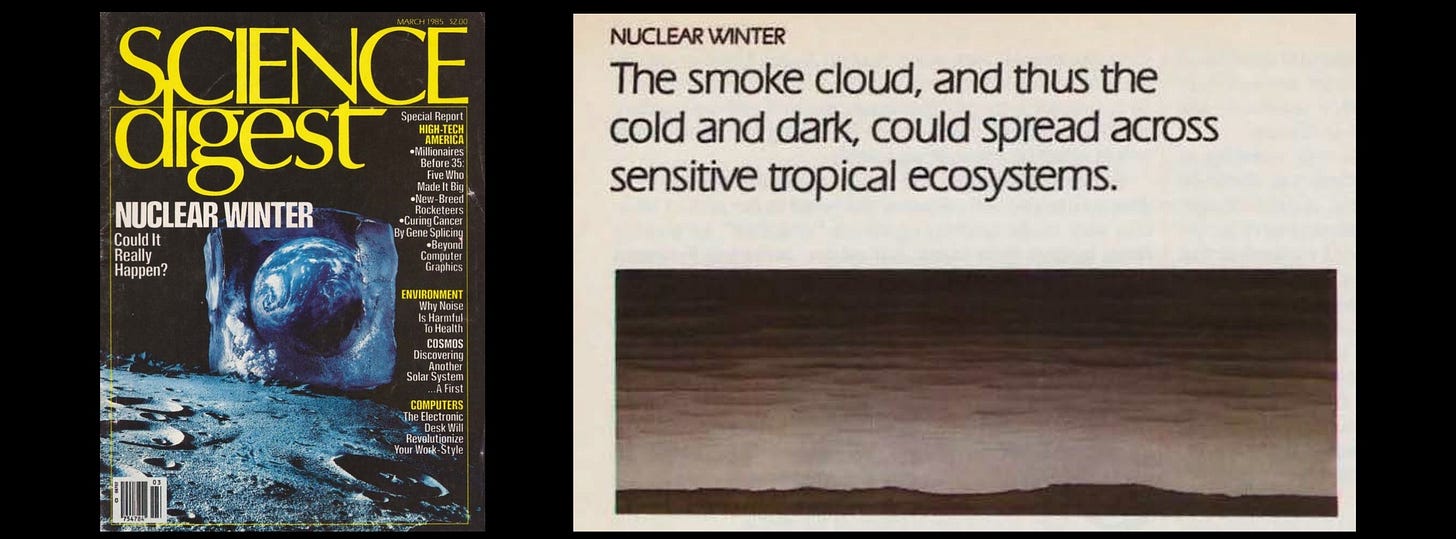

Read my 1985 cover story on nuclear winter:

My first magazine cover story on potential human disruptions of Earth's climate was not about global warming. Published in 1985 in Science Digest, the article was about the nuclear winter hypothesis that emerged as scientists estimated how much smoke could rise into the rainless stratosphere from cities incinerated in a nuclear conflict.

The initial "twilight at noon" picture was truly grim, with analyses projecting that not only would the initial nuclear blasts and radiation create local calamities, but global crop failures would follow for at least several years, potentially undermining civilization almost everywhere. Billions of human lives would be in peril.

As often happens in science, subsequent studies seemed to add sufficient nuance that the concept faded. It also faded because the Cold War itself ebbed after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Stockpiles of nuclear weapons plunged. That's when the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists set the "Doomsday Clock" as far away from calamity as it has been - 17 minutes to midnight. It's now stuck at 100 seconds to midnight, as I explored in a recent post.

Read about the Doomsday Clock's 75 years of resets.

But the threat widened as the count of nuclear-armed nations rose to nine, including Pakistan and India - where the key demonstration in 1974 was called, believe it or not, "Operation Smiling Buddha."

And a decade of recent climate research, using ever more sophisticated simulations and fresh sources of data, has strengthened the picture of catastrophic agricultural outcomes, particularly, following even a "limited" nuclear exchange.

A 2020 study led by Jonas Jägermeyr, then a postdoctoral scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, had a blunt title, "A regional nuclear conflict would compromise global food security." The findings definitely support that warning:

"[S]udden cooling and perturbations of precipitation and solar radiation could disrupt food production and trade worldwide for about a decade—more than the impact from anthropogenic climate change by late century."

It's worth pausing to weigh that. Within a short span following a modest nuclear war, solar dimming and precipitation shifts would cause more disruption of food systems than unabated human-driven global warming would do sometime toward the end of the 21st century.

The test case in that instance was a nuclear war between India and Pakistan. But the findings would be no different for a regional nuclear conflict in eastern Europe, according to a study co-author, longtime nuclear-winter scientist Alan Robock of Rutgers. He spoke about this in a Sustain What discussion I ran on nuclear winter and Putin's warm on Thursday.

The main reason, of course, is that when smoke gets into the rainless stratosphere, it disperses north and south and quickly girdles the Earth, as the animation below from one simulation vividly shows. Click here for the paper and lots more from the website of Alan Robock, someone I've been interviewing about this subject for half my life - and I'm a Medicare guy now

[Insert 3/4, 3:20pm ET - A lot depends on how much smoke is generated, and how high it rises. See the postscdript below for more.]

The Sustain What conversation included the biologists Paul R. Ehrlich and Anne Ehrlich of Stanford University, who've been studying and working to limit global environmental and societal threats for more than half a century.

In considering the implications for feeding humanity (setting aside the ecological impacts) Paul said this:

"It's not like we have a wonderfully well-fed world now and that there's no threats to the food supply without adding further disruption of the atmosphere. The threat basically is to the end of civilization. Whether or not Homo sapiens would go extinct is something we've argued about and it depends on so many factors.... But the end of civilization is something that all of my biological colleagues and I think, and most physicists would agree, is what's going to be if we have a nuclear war."

Yes, Ehrlich's 1968 bestseller, "The Population Bomb," was overwrought. (Here's a recent conversation by Ehrlich on the issues.) But he has remained a vital contributor to discourse on disarmament and sustainable development.

Watch the show on YouTube below or on Facebook, LinkedIn or Twitter:

Click here to scan a rough machine-produced transcript of the full Sustain What conversation.

My other guest was Owen Brian Toon, a University of Colorado atmospheric scientist who was one of the five co-authors of the foundational "TTAPS" paper warning of nuclear winter in 1983 and still focuses on human effects on the atmosphere and climate.

In our chat he mentioned that his 2018 TEDx talk on nuclear winter has gone from 5 million to 6 million viewers in the past week. The title? "I've studied nuclear war for 35 years - you should be worried."

And while nuclear winter is not worth fixating on, you should worry and do what you can do to change outcomes through engagement with leaders and neighbors.

Resources

Russia’s Nuclear Weapons: Doctrine, Forces, and Modernization - a March 1 report from the Congressional Research Service by Amy F. Woolf, a longtime nuclear-security analyst there.

Woolf says most analysts see Russia's doctrine as shifting from the global-scale deterrence model of the Cold War to integrating nuclear weapons into regional strategies. Here's the most worrisome passage:

"When combined with military exercises and Russian officials’ public statements, this evolving doctrine seems to indicate that Russia has potentially placed a greater reliance on nuclear weapons and may threaten to use them during regional conflicts. This doctrine has led some U.S. analysts to conclude that Russia has adopted an “escalate to de-escalate” strategy, where it might threaten to use nuclear weapons if it were losing a conflict with a NATO member, in an effort to convince the United States and its NATO allies to withdraw from the conflict."

Woolf goes on to stress that analysts are divided on the "escalate to de-escalate" component. In some ways, that may count as good news, as well, if it's true, because it means Putin's playing a game more than hovering his finger over a button.

The Biden Nuclear Posture Review: Obstacles to Reducing Reliance on Nuclear Weapons - a foundational report published in January by the Arms Control Association and written by Adam Mount, director of the Association's Defense Posture Project and a senior fellow at the Federation of American Scientists.

I'll add more, including your suggestions. Please weigh in in the comments or send me a note!

Help build Sustain What

Any new column needs the help of existing readers. Tell friends what I'm up to by sending an email here or forwarding this introductory post.

Thanks for commenting below or on Facebook.

Subscribe here free of charge if you haven't already.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues.

Hope is a verb

As I wrote a week ago and above, the prime need right now is to help those in peril in Ukraine, or on the run. This Ukrainian aid and information hub still seems an ideal starting point.

Postscript

After I posted this dispatch, Mike MacCracken, a longtime Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory climate scientist who studied nuclear war climate impacts and climate change for decades, sent a note with some cautionary points about nuclear winter in relation to the other threats from nuclear war. He noted there are "many uncertainties in how much smoke might be lofted to the upper troposphere, which is the smoke that sunlight can loft further [into the stratosphere]."

He added:

"There is just a real question about getting as much smoke lofted as is needed for the types of outcomes that were described. Back in the 1980s we scientists ran a range of smoke scenarios. I think some of the assumptions from back then have continued even though it is not clear there is enough concentrated flammable material and not considering that only some meteorological conditions are compatible with lofting.

No doubt nuclear war would be horrible on combatant nations and then, as the SCOPE study pointed out, the global economy is very vulnerable due to its nodes, so this could well clobber trade in seeds, fertilizers, medicines, food, etc. and create terrible conditions. While there may be some cooling, I don't think making it the primary reason not to go to war is justified and think the main focus needs to be kept on the direct and economic impacts."

Why is firestorm smoke worse than volcanic veils?

Here's Alan Robock explaining his team's work showing why smoke from urban firestorms ignited by a nuclear attack can have a more protracted chilling effect than volcanic eruptions that send material into the stratosphere:

"Volcanoes put sulfur in the stratosphere, and it forms these clear droplets of sulfuric acid, which come out after a couple of years and they don't absorb much sunlight. So they have an effect, but they don't last as long. The smoke is heated by the sun and lofted high up into the stratosphere, where it can last for many years. And we've had some big forest fires recently in Australia and in Canada that do that. They put smoke into the stratosphere. We observed it being heated by the sun and lofted. The same climate models we used to simulate that are the ones we're using for a much more smoke. So that just validates our work much more."