Organ Hunter

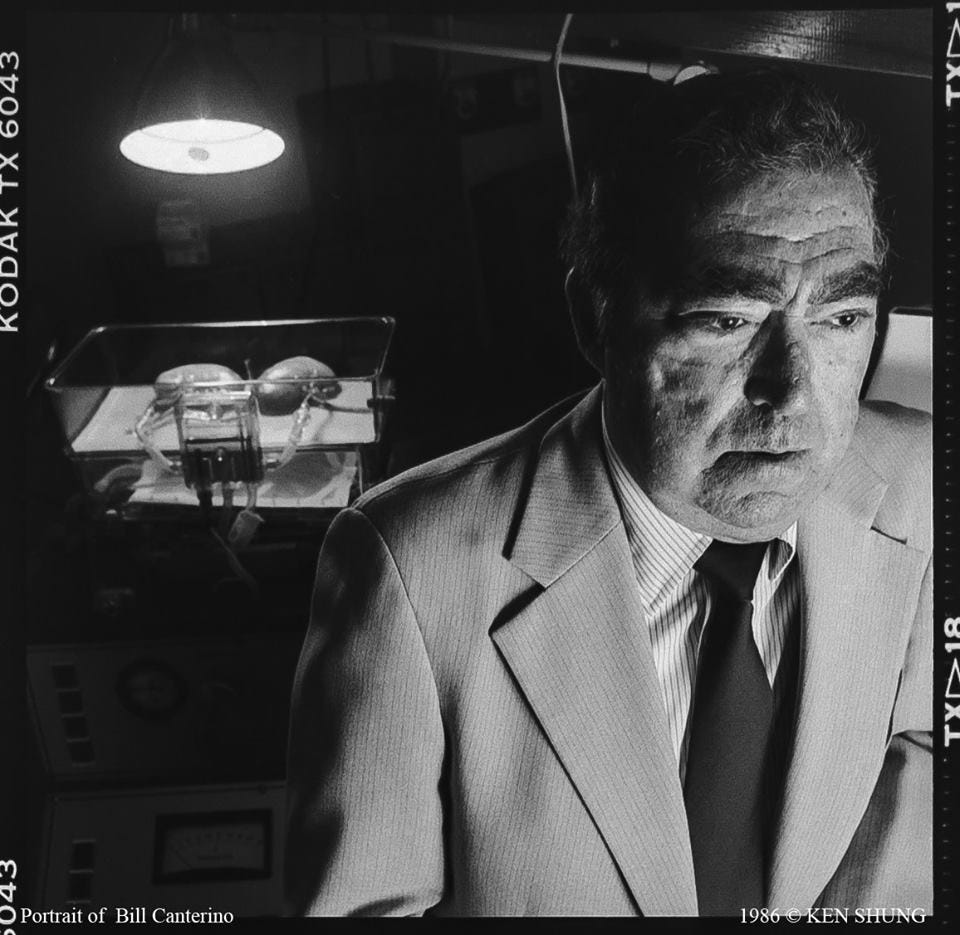

I've met some remarkable people in my 40 years of journalism. One was this homicide detective who became an organ procurement coordinator for the transplant unit at a Brooklyn hospital.

Originally published in Discover Magazine, February, 1988

Bill Cantirino is home in Brooklyn on a Tuesday night, relaxing after dinner, when a shrill beeping sound tells him there is work to be done. He turns off the electronic pager on his belt and is soon on the phone with a doctor at nearby Maimonides Medical Center. The doctor says they have a man in intensive care who looks ideal. He was carried into the emergency room the night before with a bullet in his neck.

Two policemen said the man had tried to gun them down after they pulled over the stolen Cadillac he was driving. They had both opened fire. The bullet cut a carotid artery, one of the main sources of blood to the brain. A surgeon worked far five hours trying to piece together the torn artery while others tried to keep the man alive. They finally stabilized him, but they were too late. His body was being kept alive on a variety of machines, but his brain had died.

Cantlrino gets the name of the man’s family and says he’ll be in the next day. He thanks the doctor and hangs up the phone.

For Cantirino, tragedy means business. In an average week he has two or three such conversations.

As one of two organ hunters for the Gift of Life Organ Procurement Organization, he is on 24-hour call, waiting to get word of potential organ donors. In the past decade, new drugs that prevent the body from rejecting foreign tissue, improved tissue-matching techniques, and better patient care have made organ transplantation less a risky experiment and more a standard therapy following the failure of one of the body’s vital components.

The nonprofit Brooklyn-based group, part of a growing nationwide organ-sharing network, seeks hearts, livers, corneas, even skin. But its stock-in-trade is kidneys: 8,796 kidney transplants were performed in this country in 1986. There were another 10,000 people with kidney failure waiting on lists for transplants. And 11,000 new cases develop each year (2,000 of those are patients who have already received and rejected a first kidney transplant).

Kidney-failure patients can be kept alive by dialysis, the periodic cleansing of their blood. This can be accomplished with an artificial kidney, but that’s expensive, generally requires three four-hour sessions a week, and involves restricted diet and activity. In another form of dialysis, a tube is inserted through the wall of the abdomen, into the abdominal cavity, and waste-absorbing fluid is pumped through and then removed. Both forms of dialysis require a lifetime of intrusive treatment.

The problem is that the demand for organs now far exceeds the supply. Patients waiting far transplants of vital body parts must wait far an anonymous death and far people like Cantirino to go to work. His job calls far him first to locate a special kind of death — a death in which the brain is completely destroyed but the body hangs in a sort of limbo, sustained with machines and drugs but never able to be resurrected as a living person. Such deaths are usually caused by physical trauma to the head or lack of oxygen.

Deaths that make far good organ donors are therefore usually of the unexpected kind — the result of car accidents, shootings, or suicides. Once he has located such a case, Cantirino must try to convince parents or children or spouses in the depths of grief to donate organs from the deceased. Cantirino has to be a diplomat and psychologist, social worker and undertaker, rolled into one. He is often asked why he does such a thing. And his reply is always the same: “Because l was once given a second chance.”

Twelve years ago a kidney transplant saved his life.

On Wednesday morning Cantirino calls the family of the shooting victim and arranges to meet them at the hospital that afternoon.

He drives to Maimonides hospital early, to get a look at the prospective donor and to talk things over with the hospital staff. He says he can afford to give this family a few days to make up their mind.

“As much as l would want the kidneys tonight, l would never press the family,” Cantirino says. “I would never make it a point of saying, ‘Look, lf we don’t get them now it’s too late.’ I would rather lose them and walk away.”

In 1974 his kidneys began to fall. He went on dialysis but suffered recurring infections, and the frequent sessions proved ineffective. He was told he would have to have a transplant. On March 27, 1975, Cantirino received a kidney from a murder victim, and the detective’s story made the front page of the New York Daily News. But the new kidney failed. Had a second transplant not been arranged, the failure of the first could have killed him.

In December Cantirino received another kidney, this one donated by his sister. Because kidneys come in pairs, it is possible to take one from a living donor, but the donor generally must be a close relative. This second transplant worked. Cantirino was lucky. Only a small percentage of kidney-failure patients have a living relative with a compatible tissue type. (And then, of course, not every compatible relative is able to or wants to give up a kidney. In 1986 1,887 of the 8,976 transplanted kidneys carne from relatives.)

In 1979 Cantirino retired from the police force, and Khalid Butt, the surgeon who had implanted his kidney, offered him the job of organ hunter.

In the small intensive care unit on the fourth floor of Maimonides hospital, Cantirino meets with the young doctor who called him the night before. Cantirino says he has developed personal contacts in emergency rooms and intensive care units throughout New York City; it helps speed the search.

Their attention now turns to the prospective donor. The doctor produces a blue folder labeled

“Patient Record Number Eight.” Cantirino thumbs through page after page of scribbled entries — blood pressure, heart rate, doses of dopamine and other drugs, electrocardiograms, and electroencephalograms.

“Looks good,” he grunts. “Good donor.”

Cantirino walks out from behind the nursing station and down the row of patients. A plastic rose stands in a bud vase on the counter. A transistor radio plays country music. The shooting victim is in the second bed. His chart says he is 24, but he looks younger. He lies with his eyes half closed, perfectly still except for the slow rise and fall of his chest. He is naked, loosely covered by a cotton sheet.

His body is a bit chubby, his sideburns long and uneven. There is a Playboy bunny tattooed on his right bicep. An array of tubes runs down his throat and nose, and others rise from needles in the crooks of both arms. Two pale-blue corrugated hoses run from his mouth to a mechanical respirator by the bed. They quiver in synchrony with the hiss and motion of a black rubber bellows on top of the machine.

A nurse tells Cantirino that the family is out in the hall — a few cousins and uncles, the victim’s parents and his sisters. “Most of our cases are either gunshot wounds or auto accidents,” Cantirino says. “This is typical of how you have to deal with a family, because there’s a guy who all of a sudden goes out. It’s not a case of where he had been sick or something.”

Cantirino greets them and leads the immediate family into an empty conference room. Three sisters sit stiffly along one wall. The mother, a small, birdlike woman, sits apposite Cantirino, at the far end of a long walnut table. She sits sideways in her chair. No one looks directly at anyone else.

The father sits to one side, overdressed In a heavy camel hair coat and a hat pulled down low. He periodically adjusts his brown-tinted glasses and stares at an empty blackboard.

Cantirino begins his pitch slowly, speaking gently. He says the doctors did all they could do. There is no hope. Repeating words already delivered to the family by a doctor, Cantirino says, “Your san is dead. The brain is gone completely. He lost so much blood that there was no oxygen to the brain. And the brain, when it’s deprived of oxygen, it dies.”

Cantirino carefully punctuates his delivery with pauses, giving the family time to absorb the blows.

He tells them an electroencephalogram, or EEG, a test of the brain’s electrical activity, was done that day. He says it was “flat-line” for at least a half hour — not even a spark of life. Two doctors had independently confirmed that their son was brain-dead.

“The only good that can come out of this is that two people can have a new life,” Cantirino says, now shifting to a positive tack. “It could be anybody from the age of three to the age of fifty. It could be a woman with children; it could be a girl getting married.”

The only sound is the humming of an electric clock. “I don’t know if you know anybody on dialysis, but it’s not very pleasant,” he says. “This is the only chance these people have to have some sort of life.” The victim’s mother hardly moves. She stares at the metal legs on one of the plastic chairs. “lt’s a very hard thing to ask you people, when you are losing a life, to give someone else a life,” Cantirino says. “But it’s the only time it can be done.”

There is a long silence, finally broken by the father. “l know what it is all about, these things,” he says. He speaks with a Spanish accent, slowly hefting each word like a heavy object. Cantirino, seeing he has gotten them over the first big hump, starts to lay out the situation in more detail. He says there will be an autopsy, as in any gunshot case. Giving up the kidneys will not affect any legal situation. (A sister had told him that there would be a grand jury investigation of the shooting.)

“This is a very hard decision,” the father says in a monotone.

“I’ll grant you, it’s not an easy one,” Cantirino says. “lf you look at it from the point of view that someone will be helped, then maybe it would be a little bit easier. But this is something that you have to work out yourself. I just want to tell you why we need them, who they would help.”

The father rises slowly, almost painfully. “I understand you perfectly,” he says. His wife moves to his side. Cantirino hands the father a business card and tells them to go home, to think it over. The door closes behind the couple, leaving Cantirino alone in the silent room.

He returns to the intensive care unit to tell the doctor that it will be at least two or three days before they get a decision. “They’ve just been told their son is dead,” Cantirino says. “Regardless of what he did, he’s dead. Now they have to accept this, to come to terms with it. Then they have to say okay-which I think they might, because we didn’t get a flat no. The father seems to be the strong one, yet the mother’s the one who holds the key. You can see just by looking at her that no matter what he wants, she’s the one who’ll say, and whatever she says will go.”

Learn more from the Organ Donation Alliance

By the next afternoon nothing has changed. The victim is still stable, although he is passing a lot of fluid, a nurse says. A rookie policewoman, assigned to guard the victim — who is technically a prisoner — sits idly flipping through a thick novel. As Cantirino passes he smiles at her, recalling his police days. “It’s better than walking a post,” he says of her bedside duty. She smiles back.

The family is due at noon, but they don’t show up until midafternoon, and then it’s just the three sisters. The shock seems to have dissipated somewhat, but it has been replaced by suspicion. They start to ask questions. Where will the kidneys go? Are they sold or given to anyone who needs them? When will the body be turned aver to the family?

Cantirino carefully, patiently answers each question. The body will go to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner of New York City. Because matching an organ donor with a recipient is first attempted locally, the kidneys will probably go to someone from Brooklyn. “lt’s people like us,” he says.

He says there are almost 500 people on the waiting list at the State University of New York Health Science Center alone (the Brooklyn hospital is the ninth-busiest kidney transplant center in the United States).

A match is made from a list of potential recipients at New York’s various transplant centers. The selection is based on the length of time a patient has waited, the direness of the need, and the degree of tissue compatibility. “No one can buy a kidney, rich or poor,” Cantirino says. “It’s strictly through luck.” Cantirino calls in their brother’s doctor.

The doctor’s boyish face, open collar, and deck shoes belie his authority as chief resident. He begins applying pressure. He says the number of bullets that struck the victim will be learned from the autopsy. But as far as the possibility of donating organs, it is becoming a question of time. In a day or two, or maybe a week at the most, infection will set in. And soon, the doctor explains, because of the demand for beds in the intensive care unit, their brother will have to be moved to a general ward, where the care is not as good.

Cantirino interrupts, sensing the pressure is becoming too intense. “The body on a machine doesn’t really function. It’s not normal. The liver, the kidneys themselves, they don’t perform the way they should. And the body starts to accumulate poisons in the blood. You can’t maintain the body,” he says softly, “because it’s not normal.” The oldest sister twists the leather thongs on her purse as he talks. She has run out of questions. The sisters say they will go home once more and talk it aver with their parents. The youngest one says their mother will decide. Cantirino asks them to try to decide by tonight.

“It’s never a sure thing,” Cantirino says after they have left. “l’ve had them change their mind. Had one on the way to the operating room and they changed their mind. Then they carne back the next day and said okay.” He says his job is made difficult by a lot of things: a lack of public awareness, misinformation in the form of sci-fi films and novels. “When they showed Coma in Boston,” he says, referring to the popular film about a hospital that killed patients to get organ donors, “they went forty-three days without a donor.”

Cantirino says another problem is the lack of a federal law making brain death the legal equivalent to the traditional definition of death. Forty-two states and the District of Columbia have passed such laws, and in six states, court decisions have forged legal definitions for brain death. But as long as there is no consistency, he says, there will be confusion and fear among both physicians and the public.

Even so, the situation has improved dramatically since Cantirino began his job in 1979. Then, he says, only one out of five families would give consent. His average is now three out of four. Extensive publicity of some transplants has helped, as have publicity campaigns by local hospitals. A newly enacted federal law requiring all hospitals to identify potential donors is increasing the chances of getting organs.

Cantirino and his partner, physician John Evangelista, had 130 donors in the first 11 months of 1987; that’s up from 32 in all of 1979. “At least now they know what you’re talking about,” Cantirino says of the families he has met with.

Thursday night the sisters return with their mother, who is now dressed in black. She sits in a chair in the hallway, beneath a cheap print of yellow flowers that hangs on the cinder block wall. The doctor stands to one side, talking quietly with a friend of the family. Cantirino hands the consent form to the mother. She and her daughters read it slowly. At 7:50 P.M. the mother signs the paper, indicating that she speaks for her husband as well. The doctor signs the form and makes a final entry on the patient’s chart: he pronounces him dead.

The family goes for a last look at the victim-turned-donor. There are a few sobs, but mostly silence. After several minutes they leave for the last time. The young man lies still. An endless line of heartbeats parades across a monitor aver his head. The bellows hisses, his chest rises and falls. A radio somewhere squawks tinny rock and roll.

Cantirino does some paperwork and telephones the organ recovery team at the Health Science Center. Within a day the kidneys will be sutured into place in the abdomens of two people. Cantirino heads for the door, his job done.

A nurse waves to him, smiling. “Happy hunting,” she says.

Great story, innovative