Nobel-Winning Climate Pioneers Worry About the Gap Between Insight and Action

"Some people say if we have a right prediction of climate change that the problem is solved. But it’s far, far from it."

~Subscribe here to receive my dispatches free of charge or support the project financially.~

We're halfway through a week of Nobel Prizes, with medicine and physiology on Monday, physics Tuesday, Wednesday's award for two chemistry innovators who discovered a greener form of catalyst, and prizes in literature, peace and economics still to come.

But I thought it worth taking a closer look at some insights from the two climate-focused physics laureates.

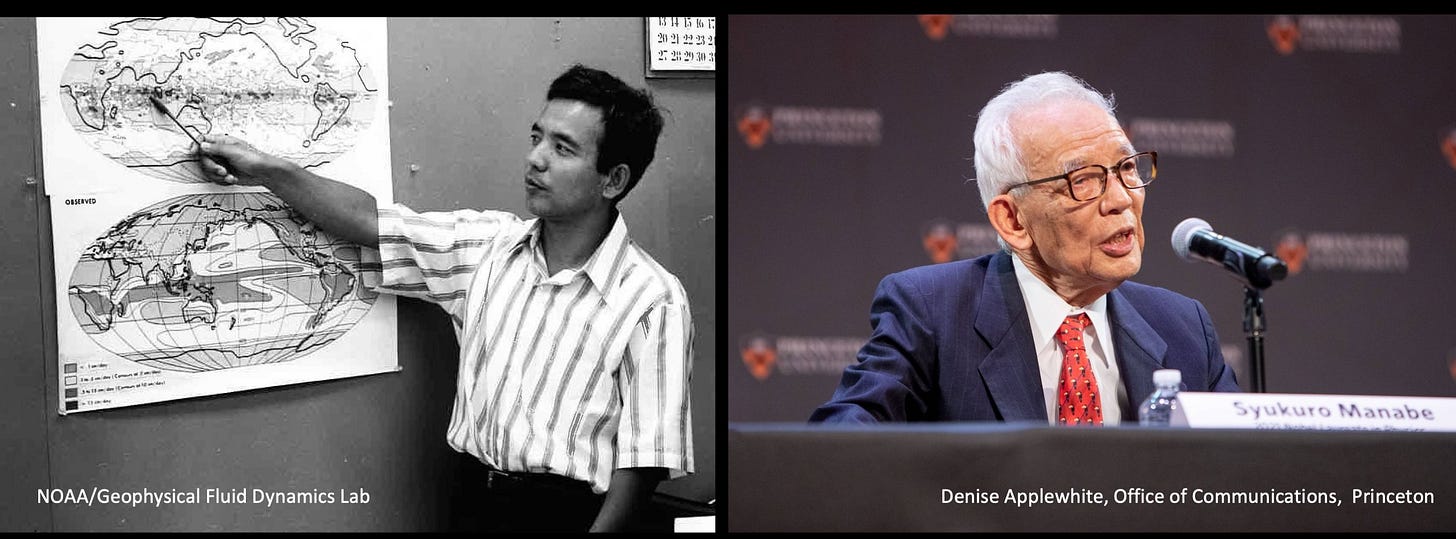

One is Syukuro "Suki" Manabe. Starting in the 1960s, Manabe's work at a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration climate lab in Princeton, N.J., laid the foundation for modern climate models and clarified the possible extent of CO₂-driven global warming.*

A 1967 paper by Manabe and his colleague Richard Wetherald was deemed the "most influential climate paper of all time" in a 2015 CarbonBrief survey of climate scientists. (CarbonBrief appropriately stressed there are many ways to gauge impact and influence, including the number of citations in subsequent research; the winner at the time was a 2003 paper on ecological impacts of climate change by Camille Parmesan and Gary Yohe.)

One of Manabe's core strengths, to my eye, has been his conviction that one can make sense of complexity without trying to replicate it. He has long been credited with the incisive, efficient nature of his models and studies - and not simply because of the constraints on computer time when he did the brunt of his work.

The other climate researcher tapped by the Nobel Committee is Klaus Hasselmann of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology. From the late 1970s onward, he devised methods for detecting signals of the rising human climate influence amid the swirl of variable conditions around the planet.

They share half the prize, with the other half going to Giorgio Parisi of Sapienza University of Rome, a physicist elucidating "hidden rules" behind seemingly random behavior in everything from gases and liquids to flocks of starlings. Here's a great piece on Parisi by a former student.

There are reams to read on the achievements of these Nobelists. I particularly recommend Kieran Mulvaney's National Geographic story kicking off with this line: "Climate models are having a moment."

I'm backing away here to touch on the winners' views on the state of climate science and the gap between science and societal response. This is important considering that Tuesday's announcement was being hailed ahead of next month's Glasgow climate-treaty talks in hopes that, somehow, the Nobel gold medals for climate science would boost countries' ambitions.

In a release, the World Meteorological Organization's secretary general, Petteri Taalas, said the award "demonstrates that climate science is highly valued and the climate science message has been heard."

One might have said the same thing, of course, after the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the U.N.'s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and former U.S. vice president Al Gore. That plaudit certainly didn't result in much - if greenhouse-gas emissions are the metric of success.

In an Associated Press video interview on Tuesday, Hasselmann, whose work underpins what is now a cottage industry of climate-attribution science, said the biggest challenge of all may be that the dimensions of the climate problem are a bad fit for human decision making:

“Human society has to get used to the fact that we have long-term problems and we need to do long-term climate policy," he said. "We have to help humanity wake up to the fact that we are experiencing climate change and it’s occurring on a time scale that we’re not used to responding to…. I think that’s been our problem from the very beginning – and it’s happening now, that people deny a problem until it’s too late.”

Manabe offered something of an amplification of Hasselmann's point in a news conference at Princeton University. (He did almost all of his work as a federal scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory located on Princeton property.*) Answering a reporter's question about climate denialism, he said his decades of trying to simulate and predict the dynamics of Earth's intertwined atmosphere, ocean and biosphere paled beside the challenge of understanding human behavior.

"It’s so mysterious," Manabe said. "Trying to predict or understand climate change is difficult, but nothing is more difficult than what happens not only in politics, but in society. It now involves not only our environment, but it’s also involved with energy, agriculture, water and just everything you can imagine. And when these major problems of society are all interwoven with each other you can understand how difficult it is to sort this thing out.

"We have to think about how to mitigate climate change but we also have to figure out how to adapt to climate change, which is happening right now, like drought and flood. We are faced with a very difficult problem. Some people say if we have a right prediction of climate change that the problem is solved. But it’s far, far from it."

Watch the whole briefing here:

Curiosity and, yes, fun

Toward the end of that news conference, the moderator opened the floor for questions from the observers' gallery and a Princeton undergrad asked what students should be doing to address climate change.

Manabe said the key is to explore and discover your particular skill and strength and always let curiosity be the fuel. And he repeatedly used a word not heard much in climate discourse these days - fun

"I really had great fun to use our climate model as a virtual laboratory of climate change," he said. "You look back in time when dinosaurs were roaming, then come all the way to the ice ages and now we are facing a major crisis called global warming."

He said he encourages students to play with a simple climate model, to gain appreciation for past changes in climate through the hundreds of millions of years predating humanity's ascent and for what is coming, depending on what today's societies do, or don't do.

Click here to explore a simple climate model offered by the education team at the National Center for Atmospheric Research:

For more

Suki Manabe's 2020 book, written with former student and collaborator Anthony Broccoli: Beyond Global Warming: How Numerical Models Revealed the Secrets of Climate Change.

Read my 2001 New York Times article on climate modeling challenges featuring Manabe: "The Devil is in the Details"

Read Spencer Weart's concise history of modern global warming science, The Discovery of Global Warming, which I favorably reviewed for The New York Times back in 2003. Weart and the American Institute of Physics have done a wonderful public service by maintaining an updated online open version of the book here. It's an essential resource, including its marvelous section on climate models.

I hope you'll subscribe here. Send me feedback (including concerns or corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a single click here.

Please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues.

_____

*The post was adjusted at the asterisks above to describe Manabe's affiliations more precisely.

Nearly all of Manabe's pivotal work was done at the federal Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, which has been doing groundbreaking work on climate change basics, hurricane dynamics and much more for decades. The Nobel Prize website and most coverage has largely failed to note this.