🎶 My Heavy Metal Days

In 1997, a chance observation watching an MTV news item on the metal band Judas Priest led me down a wonderful path

For those of you who need a break from the nonstop assault on democracy and decency, I’ve got a different kind of story to tell.

I grew up loving folk and 1960s-70s rock music, from Will the Circle Be Unbroken and Pete Seeger to Abbey Road and Neil Young. When I perform, I mostly don’t plug in.

But sometimes I do divert into other genres. Here’s my story of a very different musical journey I took into the world of studded leather, multi-story banks of Marshall amps and banshee-like shrieks. It was first published in 2001 by an Internet-bubble publication called MighyWords.com and draws on my 1997 New York Times Arts & Leisure cover story “A Metal-Head Becomes a Metal-God. Heavy.”

I’m running this piece in honor of the primal force behind the rise of heavy metal, Ozzy Osbourne. Osbourne, who’s fighting Parkinson’s and emphysema, just had his “final” (we’ll see) Black Sabbath performance - an astounding fundraising affair at a thundering Birmingham stadium featuring a four-song set with the original members of Sabbath capping a daylong show featuring a dizzying array of rock-star admirers of the emperor of metal. Here are a couple of snippets:

Osbourne’s team says all profits from the show, called “Back to the Beginning,” will go to Cure Parkinson’s, Birmingham Children’s Hospital and Acorn Children's Hospice. You can pay to watch the recorded stream.

Below you can follow my heavy metal adventure, focused on another Birmingham-born metal band, Judas Priest, which posted an homage to Osbourne on July 2 ahead of the big benefit show with this statement: “We are honored to show our love for Ozzy and Black Sabbath with our homage to 'War Pigs' - A song we play at every show around the world that fans sing along to - reinforcing their love as well for the legendary Prince of Darkness....!!”

MY UNLIKELY ADVENTURES in heavy metal and Hollywood began one night in the spring of 1997, while idly channel surfing. For no particular reason, I momentarily paused on one of MTV’s one-minute news reports, in which Armani-clad vee-jays recount the misadventures or milestones of rock stars.

Slipped in among the other tidbits was a 20-second item about Judas Priest, one of the seminal heavy-metal bands, spawned in the steel-mill black country of England in the early Seventies and carrying the torch for leather-clad, guitar-clanging rock until its legendary lead singer, Rob Halford, the self-described Metal God, quit in 1991.

Now Priest was reforming, the announcer said, adding with no particular hint of irony, humor, or surprise that the band’s new lead singer, Tim “Ripper” Owens, had been recruited from a Judas Priest copycat band, or—more correctly—tribute band, out of Akron, Ohio.

The role of a lifetime.

It just struck me as funny, charming really. A fairy tale. Some blue-collar kid from Ohio grows up admiring a rock star, carves a middle-class career aping that star in local bars, and now gets to BE that star.

I found myself recounting the story to friends for several days, the way you’d pass on the latest joke.

To me, that is always the sign of a good story, so—on a whim—I pitched the idea to the culture editors of The New York Times. Who was Tim Owens? What is it like to love something so much that you strive to imitate it perfectly? And then you snag the biggest brass ring of all. You get to become the icon you worshipped. The ultimate American success story.

My main job at the paper at the time was covering regional news, mostly about the environment, but sometimes about plane crashes, truck fires, you name it. I wrote about music occasionally, but mainly the mellow world of folk and country singer songwriters. After my Priest pitch, the music editor, a bit grudgingly, said give it a go. His hesitation derived from the fact that heavy metal was probably written about in the Times less than just about any other musical genre on the planet—including Balinese gamelan orchestras and Bulgarian women’s choruses.

But the editor was intrigued nonetheless. In bits and pieces of spare time I began making phone calls to Ohio. I tracked down a bunch of Tim’s band mates from the early days. I found his choir teacher, who adored his love of madrigals but also his tendency to pull a Freddie Mercury move once in awhile. She nicknamed Tim “Rock On” long before his rise to stardom.

I had a long talk with Tim’s mom, Sherri, and dad, Troy, before Priest’s British management clamped a lid on the family to avoid revealing sweet reminiscences about his upbringing. As Jayne Andrews, the band’s day-to-day handler, explained, “That’s not very heavy metal.”

Moms aren’t “very heavy metal”

Metal gods are not allowed to have mothers, I guess.

Slowly, Ripper’s story began to coalesce. Like any Horatio Alger tale, the saga of Ripper Owens began with working-class roots, in Kenmore, a close-knit Akron neighborhood of cozy, neatly tended row houses in the decaying heart of the post-industrial American Midwest. It was a place of tire factories and tattoo parlors, smoky bars and rusting K Cars.

His dad worked in a jewelry warehouse and his mom ran a day-care center in the living room.

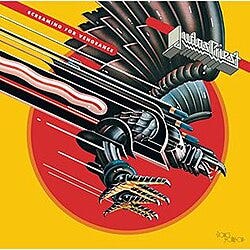

Tim’s love of Priest began in 1983, when he was 16. His older brother, Troy Jr., who worked for the phone company, brought home a copy of Screaming for Vengeance. Troy didn’t like it much, but Tim nearly wore the album out. From that moment, he was smitten. “His room—walls and ceiling—was nothing but posters of Judas Priest,” recalled Sherri.

For his eighteenth birthday, Sherri baked Tim a cake frosted with the horned monster logo from the cover of Priest’s 1984 smash album Defenders of the Faith.

This was the era when Priest was in its prime, when the band headlined a 1984 show in Madison Square Garden that was so intense, so inspiring to legions of admiring fans that those high in the bleachers ripped up hundreds of foam seat cushions, lit them on fire, and Frisbeed them through the cavernous arena toward the stage.

The gliding flaming cushions rained down like a meteor shower, with the result being a lifetime Garden ban on Judas Priest shows—and a legend that would live on forever in the annals of metal lore.

For teenagers like Tim Owens, this was intoxicating stuff. But he was not just a metal-head. He loved music of all kinds. “When I was in grade school, we all acted like Kiss,” he said. “But I was also going around singing Billy Joel. I was a huge Elvis fan.”

His parents shared his musical eclecticism, enjoying the heavy metal sound as much as they enjoyed the Rolling Stones and Dion.

Tim Owens also loved music of the Renaissance, and his supple tenor was at the heart of the prize-winning 16-member madrigal choir at Kenmore High. “He had the grungy jeans and bandanna and garage bands,” recalled Sally Schneider, the choir director. “But he also looked great in a tuxedo singing Orlando di Lasso,” the Italian madrigal composer. “He understood that madrigals were the pop music of the time, really radical stuff.”

Still, his first love was Judas Priest—a coal-fired, spark-spewing power plant of rock that pumped out pulsing streams of righteous snarl, intensity and angst nearly a generation before Pearl Jam or Nirvana made despair chic.

On weekend nights, Tim would stand at the front of the pit at Akron’s Agora Theatre, a heavy metal club, singing along on every lyric as U.S. Metal, a popular local Priest tribute band, bashed its way through Priest classics like Hell Bent for Leather:

Black as night, faster than a shadow.

Crimson flare from a raging sun.

An exhibition of sheer precision.

Yet no one knows from where he comes.

Fools! Self destruct, cannot take that crown.

Dreams! Crash one by one to the ground.

Hell bent, hell bent for leather.

Hell bent, hell bent for leather.

He watched intently as the band’s lead singer, Jim Williams, did his imitation of Priest’s Rob Halford. Night after night, Tim sang along with the show on stage, essentially beginning his Judas Priest tutorial by mimicking a mimic.

One night he was noticed by Dan Johnson and Steve Trent, two young musicians who were looking for a singer for a new metal band they were forming. “Timmy was a little pudgy kid, but he was belting out these songs so loud you could hear him over the P.A.,” said Dan. “His highs were incredibly shrill. We said to each other, ‘What about him?’ ”

Even at this entry-level stage of the music business, nothing came easy. “They had me audition to a Judas Priest song, Riding on the Wind,” Tim recalled. “They didn’t say I was in right away. I went home and they called later and I got the job.”

The result was Dammage Inc., a band that developed a loyal local following as it played songs by Judas Priest, Metallica, Slayer, and Anthrax. But Priest was always the heart of the group’s repertory. Even when the band changed its name to Brainicide and shifted to playing its own songs, Tim and his friends continued to play what had become a signature tune, Victim of Changes.

“There’s this point in the live version when Halford holds this ‘no, no, noooooooo,’ ” Dan said. “And Tim would hold that note infinitely, absolutely as long as he could. Every time, he would stagger around the stage and nearly fall down, deprived of oxygen.”

The locals loved it, even the post-punk moshers with their platinum-bleached mohawks. The band attracted a loyal following.

Tim became a student of all things Halford, from his trademark howls to his habit of punctuating some shows by riding a snorting Harley on stage. Tim acquired his own studded bracelets and collars and leather vests, unaware at the time that his idol wore them not just to promote a bad-ass image, but also because he was gay.

Many other rock musicians were aware of Halford’s private proclivities, and any student of Priest lyrics could without much effort notice the striking paucity of references to a mainstay of more overtly heterosexual bands: girls, girls, girls. And then there was the bullwhip, and song titles such as Ram it Down and Point of Entry. But most Priest fans were so caught up in the primal joy of macho metal that they didn’t have a clue.

In 1990, Brainicide headed into uncharted territory that one local fan described as “death metal meets psychotic metal.” There wasn’t much room for vocals, so Tim departed and moved full-time to the tribute-band world, replacing his first role model, Jim Williams, in U.S. Metal. He began working his way up the tribute-band food chain, but never imagined where this might lead.

The next year, while still playing in U.S. Metal, he also became the vocalist for Winters Bane, a band writing original songs in an operatic heavy-metal style that was essentially a harsher, bloodier variant of Queen.

Even though Tim was juggling lead-singer spots in two bands, music remained a sideline. Unlike many of his friends, who were unemployed or footloose factory workers or scraping together a living doing guitar repairs or the like, Tim had a daughter from an ex-marriage and so had to keep the money flowing with a string of day jobs.

Through the early Nineties, he was a purchasing agent for Akron’s oldest law firm, Buckingham, Doolittle & Burroughs. “At work Tim would be conservative—no earrings, short hair,” said Robert Forwark, the firm’s purchasing manager. “We’d go out golfing.”

In October 1991, tensions about the marketing dilemma surrounding Halford’s sexuality rose within Priest. And after a nearly disastrous stage accident—in which Halford was clobbered in the face by a piece of metal while waiting on his Harley—he quit.

The breakup came just as metal hit its all-time nadir. Nirvana and the Seattle sound were tugging MTV and radio in a new direction, and metal sales slumped. This was metal’s Dark Ages, a period many fans recall with venom, feeling that these new genres had been built on the backs of Ozzy, the Metal God, and the rest—but that the progenitors of the hardest kind of rock were not acknowledged.

None of this kept U.S. Metal from gigging on. The mission simply changed: from celebrating Priest through admiring emulation to carrying the torch, keeping the flame alive like the monks who guarded books through the darkness and anarchy of the plague years.

There was always the chance that Priest would reunite, metal would rebound. In the meantime, it was up to U.S. Metal and Priest tribute bands around the world to play the songs in whatever biker bar or roadhouse would have them.

Buddhist Priest, Nudist Priest…

There were Priest copies everywhere, including Just as Priest in Norway, Buddhist Priest and Nudist Priest—no kidding—in Los Angeles. And, indeed, the latter band performed all the Priest classics in the buff. (Rob Halford, with a chuckle, recently told me that Nudist Priest is the one tribute band he’s interested in seeing.)

In the meantime, Tim’s side effort with Winters Bane was working out well. In 1994, Bane recorded an album for a German label, Massacre Records, which sold about 8,000 copies in Europe and Japan but was never released in the United States.

Massacre tended toward the death metal sound, with other bands on its roster including Afflicted, Atrocity, and Lavatory. Thomas Hertler, the label’s A&R manager, recalled Tim and his band with affection. “They were pretty original fresh power metal, with a good singer and good attitude,” he said.

To help raise its profile back home, Winters Bane worked out a clever touring technique in which it was the opening act for another group, British Steel, a Priest tribute band. The twist was that the bands were really one and the same.

Bane would open with a set of originals; challenging audiences around the Midwest with its harsh, bloody take on life. After a quick costume change, the players would reemerge as Priest clones, eliciting cheers from audiences eager for a dose of classics like You Got Another Thing Coming and Living After Midnight.

“It worked great,” Tim said. “We went from getting $50 a show to $1,000. I’d sing 45 minutes of Winters Bane originals, then put on the leather and do two hours of Priest. People would look up and say, ‘Hey, isn’t that the same guy?’ ”

Tim left the law firm and took a Tuesday-through-Thursday job as a traveling office-supplies salesman. The schedule meshed far better with the music.

He was in a good groove, rather satisfied with a life that was providing income and feeding his passion for Priest. His one dream was to meet the band he spent so much time imitating. A hardened realist, he never imagined that there was any sense in dreaming that he might become a member of Priest.

His wish was partly granted one night when Steel swung further off-field than usual and played in Virginia Beach, the hometown of Scott Travis, Judas Priest’s drummer (the only American in the band and one in a long line of Priest drummers, almost as long as the sequence of drummers in Spinal Tap). Scott was at the club and was sufficiently impressed with the tribute that he took over the drum kit and joined in on Metal Gods, one of Priest’s hallmark anthems.

For Tim, this represented a pinnacle of sorts. “I was so amazed that I’d met a member of Judas Priest,” he said. “I was in awe.”

Unaware that bigger things were to come, Tim stuck to his routine, selling office products by day and singing by night. British Steel traveled from Wisconsin to western New York State, developing loyal fans in towns like Buffalo and Altoona, PA.

But metal was fading and grunge was ascendant. In 1995, Tim followed the musical tide and joined Seattle, abandoning his Halford act and now working to perfect Eddie Vedder’s deep, throat-clenching grunge sound.

Tim did well in his double life, making enough money to buy a used Jaguar sedan. He got a Judas Priest tattoo, but high enough on his shoulder that the sleeves of golfing shirts hid it. That way he wouldn’t raise eyebrows when he played with daytime friends at a local country club.

By this time, the same musical tide that prompted him to abandon heavy metal for alternative rock had also relegated his long-time heroes to the discount bins in music stores.

The last time Judas Priest made headlines was in 1990, when a trial judge in Nevada rejected a $6.2 million product liability lawsuit claiming that subliminal messages in a Judas Priest song had prompted two maladjusted teenagers to shoot themselves in the head.

After selling 15 million albums, Priest was essentially dead and buried. The band’s loyal following was a blip compared to the masses buying U2 or Nirvana or Red Hot Chili Peppers or...Aerosmith. Well maybe there was hope. If Steve Tyler could do it, if the Stones could keep at it, maybe metal—and Priest—had a chance.

“After nigh on 20 years of blood, sweat, and tears, we’d always said that if a key member left we’d call it a day,” said Glen Tipton, who, along with K.K. Downing, had provided Priest’s signature texture of dueling guitars (and dueling mops of pin wheeling hair). “But,” Glen said, “we spent some time with families, got a grip on life in general after so much life on the road, and thought we have a few more albums in us. We decided to look for a new singer.”

In 1993, they quietly began searching for a voice, someone who could come remotely close to giving the band the front-and-center presence, the aura, the power, of Halford.

They listened to hundreds of tapes and auditions of talented singers, but no one was quite right. By the fall of 1995, they narrowed it down to 50 or so, then 20. “We’d used up a serious amount of brain cells and had narrowed it down to 15 guys who were poised to come over,” Glen said, adding that they all had great voices. “The actual caliber of singers on this planet not doing anything of note is quite frightening, really,” he said.

Then, at the last minute, through a series of chance events, Tim’s vocal talents and ferocious stage manner came to the attention of his idols.

It was all really thanks to two women from upstate New York who were hard-core groupies of both the real band and Tim’s tribute band. In 1995, Christa Lentine, a tanning-parlor attendant from Churchville, NY, and her cousin Julie Vitto, from Rochester, had made a grainy, jerky videotape of Tim doing his Rob Halford role in British Steel at Sherlock’s, a club in Erie, PA.

The women knew Scott Travis, Priest’s drummer. Christa knew Scott particularly well. She was dating him. After Steel wrapped up its show, “they said Judas Priest is going to get this tape,” Tim recalled. “I said, ‘Yeah, right.’ ”

A few months later, as Scott was packing to head from Virginia to England for that final round of vocalist auditions, Christa stuck the old tape of Tim in one of the drummer’s bags.

“I said, ‘You’ve got to check out this guy,’ ” she recalled. “Scott didn’t have any interest. He said they weren’t looking for a Rob clone.”

Nonetheless, over in Wales, where the band was preparing for the tryouts at the farm that doubled as its recording hideout, Scott Travis and his band mates decided to watch the video, almost as a lark.

They were incredulous as they heard Tim’s voice alternately growl and soar and watched him prowl the stage; his black leather and close-cropped hair were remarkably similar to that of their former front man.

“I’ve seen some amazing things in my life,” said Glen. “But I couldn’t believe this.”

Then came a cascade of phone calls, first from the band to Julie Vitto to find out if the tape was doctored (“I said, ‘Tim’s for real,’ ” she told them), then from Julie to Tim. At first he thought it was a joke.

But then he was told to call Jayne Andrews, the band’s aide.

When he reached her, her first question was: “Have you got a passport?” Tim recalled.

Two days later, in January 1996, he was on an overnight flight to England and then—in a blur of uncomprehending motion—heading by car to Wales. The green countryside swept by and the car pulled up to an ancient house.

“I could hear music inside,” he recalled. “I walk in the dining room, and there’s this giant table. There’s Ian Hill (the bassist). And then there’s Scott way down at the end playing drums. And Glen sitting on an amp, jamming. You’re used to seeing them on posters all around your room, and then you’re there with them.”

Glen suggested that Tim eat something and get some rest after his long trip. He could try singing tomorrow. “But I said, ‘Let’s do it now,’ ” Tim recalled. “There was no way I was going to sleep.”

The band, an engineer and Jayne Andrews retreated to a glass booth and started rolling a voiceless tape. The song was Victim of Changes, Tim’s old standard from his days in Brainicide and then U.S. Metal and then British Steel.

He roared into the first verse, “Whiskey woman, don’t you know you’re driving me insaaaaaane....” The note ripped through the air like a blade. But Tim was interrupted as Glen cut short the tape, hit a button, and spoke over an intercom: “You’ve got the job.”

“We’d listened to literally thousands of singers,” Glen said later. “Russian, Eskimos, men, women, people from all corners of the world, knowns, unknowns. But here we knew without a shadow of a doubt we’d found our man. He went out there and completely stunned us.”

Tim, still not quite believing what was happening, sang a few more tunes, including The Ripper, a dark ode to the fiend who stalked prostitutes in London’s 19th Century coal-black fogs. Glen and the others immediately decided that Ripper should be the newcomer’s stage name.

They went out to a nearby pub to celebrate with steak and beer, snapping photos that held a jarring mix of war-wizened, wiry, middle-aged rockers and this beaming, pudgy-cheeked kid with a baseball cap and mile-wide grin. The snapshots had the feel of scenes from Woody Allen’s Zelig, with some unlikely Everyman morphed into a ridiculously improbable situation.

The rock stars were closer in age to Tim’s parents than to Tim, but that no longer mattered. They were bonded, welded, by heavy metal.

The next morning, Tim was driven to the airport for the trip back to Akron. His parents picked him up in Cleveland, and as they headed home through the winter slop and slush he gave them an autographed snapshot of him and the boys. On it he had scribbled: “Mom and Dad, dreams do come true. I love you.”

He was supposed to keep all of this secret. But soon word leaked around Akron and then onto the Internet. By May 1996, magazines devoted to heavy metal were announcing that Judas Priest was back.

Tim signed a lucrative contract, but kept singing with Seattle and selling office supplies into early 1997.

He stuck to his routine, inviting friends to the backyard barbecues he threw at his rented row house, the one right next door to that of his parents.

He did finally take an unlisted telephone number, and planned to move to his brother’s neighborhood, where split-levels on 1.3-acre lots could be had for $130,000 or so. Not the kind of guy to jump to a gentleman’s farm in Wales. A slice of suburbia would do quite nicely.

Tim’s father, a Priest fan from way back, celebrated his fiftieth birthday by having his ears pierced and getting a tattoo on his arm just like his son’s.

His mom began getting frequent phone calls from Glen and the other band members. “It’s like we’re in a dream,” she said.

Aside: When I turned in a first draft to The Times, the Arts & Leisure editor, Connie Rosenblum, did something I never experienced as a writer before or after. She asked me for more. I dug deeper and Carl Lavin, a Times journalist and friend, had roots in Akron and offered to do some shoe-leather reporting on a trip there.

The discovery of Tim Owens provided a decent shot in the arm for Judas Priest, which first signed with CMC International Records, a label devoted to what it called heritage acts, the same faces you see these days on Where Are They Now, the VH-1 series about bygone rock stars—Pat Benatar, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Eddie Money....

For Priest, this was still a scaled-down resurrection. This was a label aimed at selling a few hundred thousand CD’s per act, not millions. And the band’s first tour with Ripper took it through dozens of small 800-seat or 1,000-seat venues. No more Madison Square Garden—not yet, at least.

For Tim, though, this was a dream come true. He had ascended to Olympus, was standing on stage with his idols, singing their songs to their fans.

As the tour opened, Ripper faced a series of magic, tension-filled moments when he strode in front of a room of head-bangers weaned on Halford who now confronted this sweet-cheeked American kid.

I went to one of these shows, driving through an ice storm to The Chance, a heralded old club in the downtrodden Hudson Valley town of Poughkeepsie. Heading in to the show, some fans expressed skepticism. But then....

“What’s my name??” Ripper roared.

“Ripppppperrrrr!” the crowd roared back.

“I can’t hear you. What’s my name????” Ripper roared once again. “Rrrripppppperrrrr!!!!” the crowd roared back.

He tore into a hypersonic string of Priest classics. Then he sang a new one. Amazingly, many people in the audience sang along, having already memorized the material from the first post-Halford Priest album, Jugulator.

Ripper was for real. Behind him, Glen and K.K. smiled at each other as their guitars unleashed machinegun bursts of harmonized, soaring melodies. Their golden manes did things normally only seen when models shake their heads in shampoo commercials.

Scott bashed his drums. Ian Hill, sturdy as a Knight of the Round Table, poured thunderous bass notes through his mountain of Marshall amps.

The crowd roared. They jabbed devil-head hand salutes high in the air. Leaning over the edge of the balcony, a line of frothing metal-heads whipped their hair to and fro, signaling their approval.

“Priest, Priest, Priest, Priest,” they chanted.

My profile of Tim in The New York Times was quickly followed by a feature in GQ, of all places, and a segment on MTV, although Priest’s management fought the producers over that project because the band was starting to fear that too much focus was being put on the new kid.

But that was just the beginning. Along came Hollywood. The morning after my story ran, I received two phone calls from producers. Somehow, this took me by surprise. I’d been lucky enough to have a book turned into an HBO movie once. It was The Burning Season, my biography of Chico Mendes, the murdered Amazon rain forest activist.

This time, I didn’t get it—at first. Then one of the producers, Robert Lawrence, who made the hit teen comedy Clueless, spelled it out for me. “This has got to be a movie,” he said. It was every kid’s dream come true…a heavy-metal fairy tale.

It didn’t hurt that Billy Gerber, a top executive at Warner Brothers, played in an upscale garage band. Some movie projects languish for years, decades. Others seem to levitate and slingshot forward like a bullet train. Metal God, at least that was it’s working name, was a runaway train.

The band and its managers decided not to get involved, even though a movie like this might be their last shot at a return to those arenas they left so long ago.

The screenplay was commissioned almost immediately. The writer, John Stockwell, threw himself into the research, checking out some Priest shows, flying to concerts by Slaughter and Anthrax to note details of groupie etiquette, heavy metal essentials like the technology of flashpots, the pyrotechnic devices ignited to create geysers of fire, and the like.

Drafts came and went and the plot quickly shape-shifted from fact to fiction. Judas Priest became Steel Dragon. British Steel became Blood Pollution. Akron became Pittsburgh in the Reagan-era Eighties. Ripper became Izzy. Heavy metal references were slowly expunged, once the marketing folks had their way. Metal wouldn’t attract the right demographic, they said.

Punch-up guys were brought in to add gags and frat-joke humor. Callie Khouri, who wrote Thelma and Louise, was hired to invigorate the fictional romance between the star and his girl. The story became that of a young man torn between his idealistic rock ‘n roll dreams and love.

The story line went far beyond Tim Owens’ own unlikely trajectory, projecting ahead along his life curve and inventing a happy ending in which the protagonist, a tribute-band perfectionist, finally realizes that being a copycat isn’t enough, that he has an identity of his own.

Izzy moves to Seattle, wins over his estranged girlfriend, and—along the way— invents grunge rock. Hey, why not? It’s a movie.

The green light came from above.

Then it was casting time. Brad Pitt seemed deadset on playing a rocker in his next movie and circled this film and another music movie for weeks, with producers offering to fly him to Vegas on a Warner Brothers jet to catch a metal show. But he pulled out and Mark Wahlberg took the role, fresh from weeks of seasickness on a sound stage in Burbank where The Perfect Storm was being shot.

Pitt’s soon-to-be-wife, Jennifer Aniston, settled in for the co-starring role of steadfast girlfriend.

The cast was filled out with a host of real-life rockers, including Zakk Wylde, the long-time lead guitarist for Ozzy Osbourne, Jason Bonham, the drumming son of Led Zeppelin’s skin-basher John Bonham, Blas Elias, the drummer for Slaughter, Stephan Jenkins, the front man for Third Eye Blind, and Brian Van Der Ark, the lanky singer guitarist-songwriter from the Verve Pipe.

I was invited to visit the set and arrived late one evening at the Los Angeles Sports Arena, a faded, aging structure plunked down near the riot zone of that sprawling city like a flying saucer that lost its way. Stage lights with colored filters lit it up in green and blue splotches and vintage cars rolled into the parking lot to make this look like Reagan-era Pittsburgh.

During a break, Stephan Jenkins, playing the singer in a competing Steel Dragon tribute band, said it all reminded him of his high school days, when he got into a fistfight with another student over the relative merits of Judas Priest and the Police. Jenkins was a Police fan and loathed metal. The other student threw his book bag and moments later fists were flying.

Jenkins said he used those recollections to inform a fight scene in which he and Wahlberg tangle in the parking lot.

Brian Van Der Ark said he’d played in a Kiss cover band. Zakk described how aspects of his life mirrored Ripper-Izzy’s career. He’d been playing in a string of New Jersey metal bands and was just 19-years-old when metal’s Zeus, the wizard, Ozzy himself, tapped him.

Zakk, who plays one of the guitarists in Steel Dragon, provided helpful hints to the director, Stephen Herek, about life, sex, chord structure, and other essential elements of the metal universe. His real-life guitar tech ended up playing his guitar tech in the film.

At the arena that night, the parking lot filled with mock metal-heads—and some real ones who’d gotten hired as extras based on their garb and hair. The filming was a surreal moment in which mock fans swarmed toward a mock show by a mock metal band, with mock tribute-band members putting leaflets under windshield wipers advertising their mock copycat show.

If ever there was a moment when art imitated life imitating art, this was it.

I looked at a list of the several hundred electricians, costumers, hair dressers, gaffers, assistants, caterers, even someone whose job description was pot washer, who were employed—at least for a few months—because I had once watched a 30-second bit on MTV.

I got a bit carried away in all the metal dreaming. Being a musician and songwriter on the side, I thought, hey, I wrote the story that inspired this vast movie-making machine; maybe I can get a song into the film. I retreated to a friend’s studio and we did our heavy-metal best, producing a crunching demo of Heavy Metal Fighting Machine, a song I thought would play perfectly over the parking-lot fight scene.

My fantasies, unlike those of Tim Owens, were quickly dashed as the music supervisor—surprise, surprise—chose tunes penned by Sammy Hagar, by Marilyn Manson’s bass player, and the like.

Oh well. Back to The Times....

On its way to completion, I attended a screening of a rough cut of the film, which would morph—again at the behest of the marketing gurus—from Metal God to the more generic Rock Star.

There it all was, the grimy blue-collar streets, the starry-eyed copycats, the wonder of arena rock, writ large and welded to the retina with pyrotechnics and the eardrums by banks of maxed-out Marshall amps.

There was Izzy, climbing to Olympus to claim his place as a metal god, then getting altitude sickness—along with a series of wicked hangovers—and eventually wandering in the wilderness until he finds himself and Jennifer Aniston.

That was it for rock ’n roll and me. I returned to more mundane reporting duties, like covering international negotiations aimed at creating a treaty to combat global warming.

In reflecting on all of this, I decided to return to the story’s roots and check in on the Metal God himself, Rob Halford.

He appeared at Madison Square Garden recently [August 5, 2000], this time not as a headliner, but the opening act for Iron Maiden, a band that once opened for him.

He was trying to kick-start the stalled Harley that had been his career ever since he quit Priest to pursue his own muse. Halford had put out a series of albums in various incarnations, none of which found a mass audience.

This time, singing and touring simply as Halford—with his own set of dueling guitars—his engine seemed to be sputtering to life, getting ready to roar. His new album was titled simply: Resurrection.

In the afternoon before the show, Halford sat in a bar at his hotel near the United Nations, reminiscing about the weird and wonderful trip he’d been on over the last 30 years—a span in which he rose from being a kid traipsing past the smoke-belching steel mills of Birmingham and listening to their rhythmic thuds and clangs to being a rock star so worshiped that Tim Owens and other admiring singers built their own careers imitating him.

And, stranger yet, now Hollywood had found Tim Owens’ story so appealing that it had made a movie imitating HIM.

“It’s all rather amusing, really,” Halford said.

With a lighting-bolt tattoo on the right side of his shaved head, his Ringo Starr nose protruding from a Silly Putty face, and a cluster of male groupies hovering nearby, Halford looked more like a bouncer in a downtown biker joint than an icon of the heavy metal world of big hair and top-heavy girls.

Yet this was indeed The Man, the Metal God, and the primordial screamer who helped invent the heavy metal sound.

All the emulation and simulation was also rather flattering, he added, saying he loved being idolized.

“I am the Metal God,” Halford said, smiling. “This is the ultimate accolade, for people to go so far as to create some kind of tribute. That only happens for the right reasons, because you meant so much to them.”

He added another plot twist that hadn’t even made it into the fictional movie: Halford strongly implied there was a chance he might someday reunite with his old band.

He took responsibility for the breakup, saying over and over how often he thought about the bad old days.

“I miss it passionately,” he said. “I miss everything about it. I’d be a liar if I didn’t say so. The combination, the chemistry of the music. We developed into a family.”

For the moment, though, he had the unalloyed joy of going out on stage as himself.

That night, as he strode to center stage—in stark contrast to the bad old days—the arena was still filling up and the house lights were not yet dimmed.

Some of the assembling Iron Maiden fans barely took notice. But for the older ones and the aficionados, this brief opening set was exactly what they had come for.

In a blaze of light, Halford leaned over his microphone, his shaved head gleaming, and his black and red leather suit shining. His piercing tenor slashed across the arena, cutting through the thundering drums and bass, playing off the cascading leads of his two guitarists, who crawled and strutted stage left and right like the cockroach in Metamorphosis.

One of the strange and wonderful things about heavy-metal concerts is that at certain moments the lighting director always points a bank of halogen lamps at the audience, not the performers.

And the reason became clear less than a minute into Halford’s rendition of the title song from his new album. That’s when he held his microphone out toward his disciples, and they—on cue and lit up by a sudden flick of a switch—echoed the lyrics back at him, fists pumping, heads banging, beers splashing.

A heavy metal performance is a two-way street, kind of like a concert version of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. No punkish moshing chaos here. If you don’t know the lyrics, if you’re not prepared to pump your fist in synchrony, you risk embarrassment, or worse. And so he and his minions sang the song together.

Once again, Halford was god. No teased hair or Spandex here, no deeply-cleaved babes gyrating on stage, no Van Halen gymnastics. This was leather-and-studs serious stuff.

Opening acts have it tough. While Halford was ripping through his 30-minute, eight-song set, the arena was filling, with some Maiden fans still in the Garden’s bars getting stoked.

But Halford’s hardcore fans and he were oblivious to the empty seats and shuffling figures holding out ticket stubs.

The music pounded chests and eardrums like a sonic broadside. The audience, mostly middle-class guys from the bridge-and-tunnel suburbs of Jersey and Long Island, howled in ecstasy.

“The Metal God is back!” Halford roared.

Right on cue, the audience, bathed in a halogen flash once again, roared their righteous approval.

He finished his set without an encore—the curse of the opening act.

His worshipers, already hoarse from screaming, raced up the ramps toward the arena bars, high-fiving and kicking things and jumping up and down.

Between gulps of beer, one of them, Sean Tobin, a carpenter from Lawrence Harbor, N.J., recalled his first Priest concert, which he saw when he was 12, back in 1982.

Last year, he said, he saw Ripper at a Priest show in a Manhattan club. It was the next best thing to real, but still felt a bit like a play within a play.

“It filled a void, like a cover band would,” he said. But it was not Halford. He said he had nothing against Ripper, and that the guy from Ohio was “living out the dream we all had.”

Now, though, he had just had a 30-minute dose of the real deal, and he was reeling, flying, supercharged.

“Halford fucking ruled tonight. Write that!” he said.

He wasn’t staying for the middle set by Queensryche or for the headliners, Maiden.

“I came for this,” he said. “I came for the Metal God.”

Where are they now?

Halford did return to Judas Priest and made this wonderful comment about metal culture at the 2022 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremonies: “We call ourselves the heavy metal community, which is all-inclusive. Doesn’t matter what your sexual identity is, what you look like, the color of your skin, the faith you believe in or don’t believe in. Everybody’s welcome.”

“Rock Star” on screen

The movie would be tweaked and trimmed and adjusted and then it was on to the theaters. “Rock Star” launched exactly one week before September 11th, 2001, guaranteeing it little theater time. But you can still watch on streaming sites.]

Tim “Ripper” Owens has been singing ever since in several bands. He tours now with longtime Judast Priest guitarist K.K. Downing the band KK’s Priest.

Parting gift

If you got this far you deserve this studio-produced performance of Black Sabbath’s “Mr. Crowley,” with Jack Black supported by the next generation of heavy rock royalty, Roman Morello, Revel Ian, Yoyoka Soma and Hugo Weiss.