Please click the ♡ button if you appreciate my work. This helps boost post visibility.

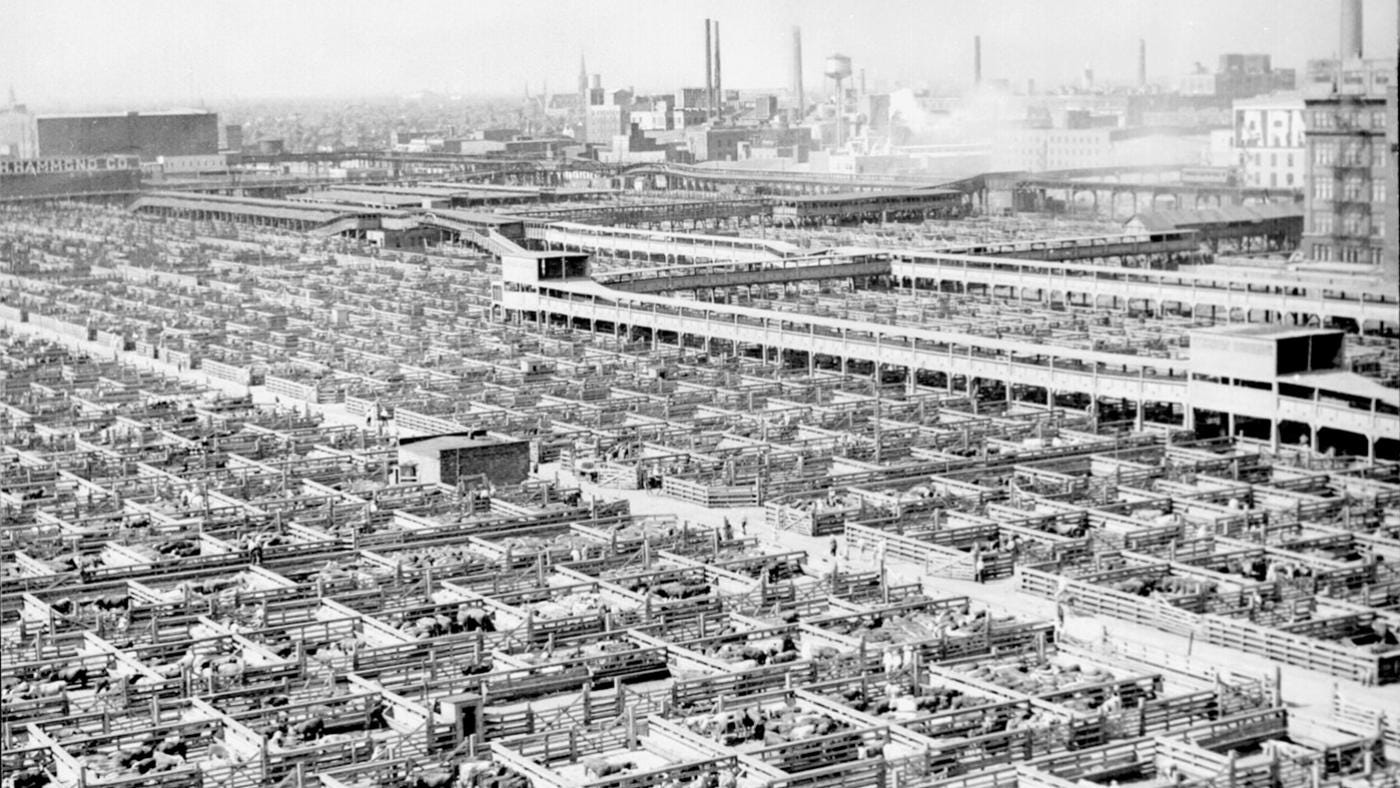

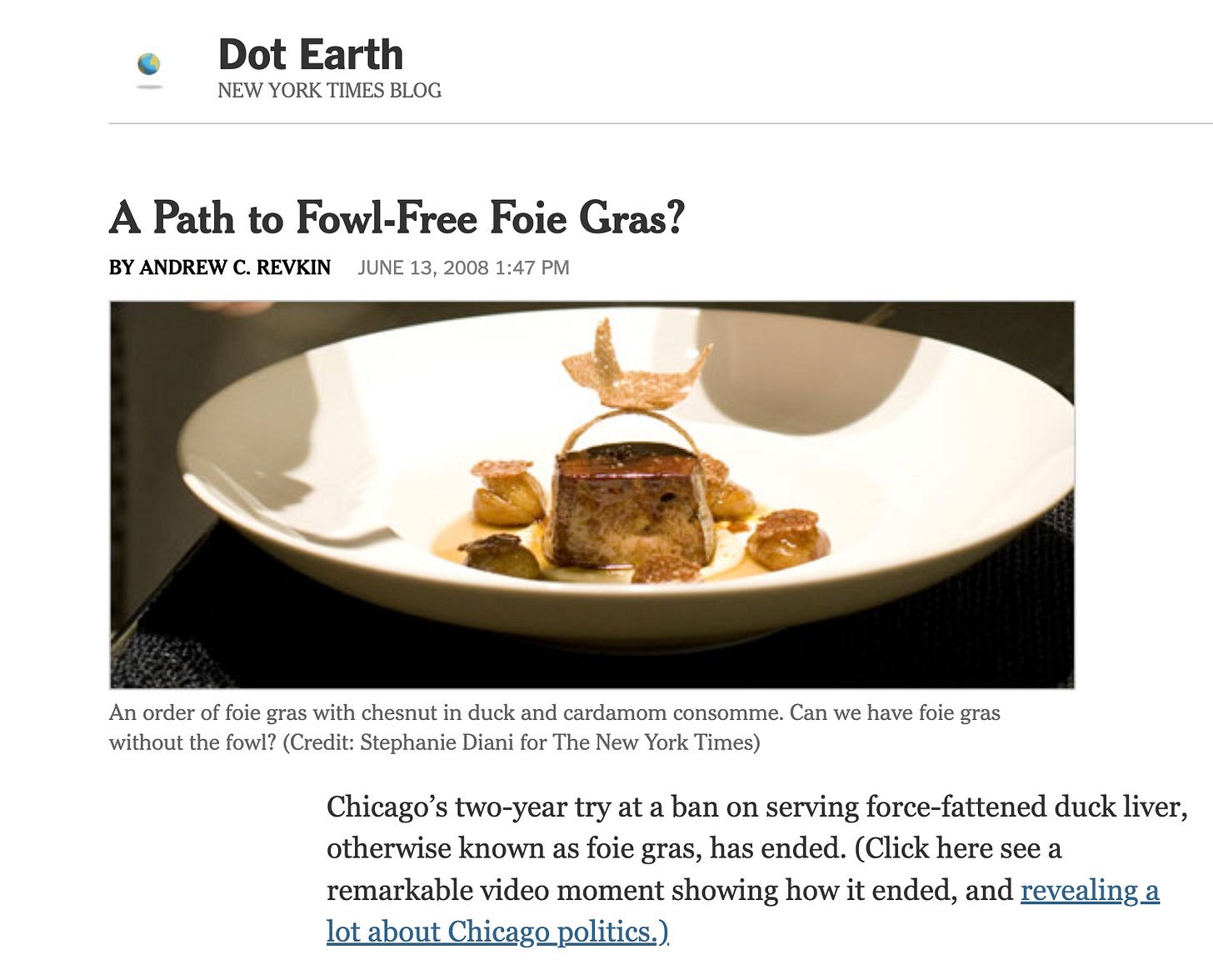

Since 2008, I’ve been expressing zeal for the possibiliity of meat without cruelty and slaughter. That’s the year I proposed a lab-grown variant of foie gras, given the highly proliferative quality of liver cells, the horrible impacts of conventional production, and the high price (meaning easier profits than with, say, nuggets). Here’s some of what I wrote after Chicago ended a temporary ban on serving force-fattened duck liver:

There’s a bigger question here, though, relating to how humans — as populations grow and grow more prosperous — choose to relate to the other inhabitants of this very finite planet. Sure, foie gras production is an ancient practice, with roots more than a millennium old. Sure, it’s delectable (to some). But suppose there are alternatives to producing a delicacy like this that don’t entail penning thousands of birds in dark sheds and sticking a pipe down their throats three times a day for the last 2 or 3 weeks of their 12-week lives until their livers swell about tenfold. Remember, this isn’t just about a few rich people in Chicago. China is just getting into high gear (both on producing such food products and, with its swelling ruling class, consuming them).

I have a proposal: Keep the liver; free the ducks. This will take awhile, of course. After all, it involves the frontiers of food technology — making meat in a lab instead of a feed lot. There’s a growing international push to do this, at least for nuggets and ground meat — for both environmental and ethical reasons. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals has even offered a $1 million reward for affordable cultivated meat.

I think foie gras could be the perfect test case, all you cultured-meat entrepreneurs.

I also have also made a plant-based alternative “faux gras” with chick peas, mushrooms and other umami ingredients.

Meat wars and realities

Both plant-based meat substitutes and lab-grown meat have, after spasms of counterproductive hype, been making slow progress. Sadly, culture-war politicization is toxifying the entire arena. That’s why I found this new post by Alex Smith of

particularly welcome. It cites two new preprints (he’s a coauthor of oine) and comes away with valuable conclusions that cut against the politlical and protectionist rush to ban lab-grown meat and against countervailing arguments for a rapid end to livestock cultivation:Here’s a key takeaway section:

There are plenty of things for politicians to do to support agricultural producers. It’s abundantly clear that banning cultivated meat or attacking plant-based products is not one of those things.

It’s also abundantly clear that alternative proteins won’t save the world, at least not by themselves.

Yes, alternative proteins have environmental benefits, even if they simply limit the growth in demand for conventional livestock—especially beef. But as long as they are not on track to significantly displace conventional meat, they will not be a meaningful strategy to reduce the carbon footprint of agriculture.

Rather, improving livestock production efficiency, adopting methane reduction technologies for beef production and manure management, and working on piece-meal strategies to decarbonize livestock production must also be taken seriously as ways to reduce the greenhouse gas impact of agriculture.

None of this will radically change the face of agriculture. Ranchers will ranch. Farmers will farm. That’s an unappealing future for the many advocates and activists who wish to see factory farms shuttered, society veganized, and farm animals set free. It’s an equally unfortunate future for the politicians and pundits who need to create chaos to win the culture war.

But at the end of the day, it’s a future where abundant meat—whether conventionally produced, made in a factory, or produced from plants—can feed a cleaner world.

The home plate

Our family menu reflects the hybrid realities of today’s food mix, and our eagerness to eat ethically and with an eye to sustaining thriving landscapes and local communities. We’re ominivorous, but with ever rarer beef and pork in the mix, as in this eggplant and sausage mixed grill last summer.

And the meat we do consumer almost all comes from local sources, particularly Bob Bowen of Sunset Acres Farm & Dairy in Brooksville, Maine.

A tactic for crossing tough cultural divides over food

I also hope you’ll listen to my recent Sustain What conversation with my friend Zoe Weil, who’s a hyper-fit vegan who’s spent her career helping foster education models that result in sustainable and humane living. The full conversation is below but here’s what Zoe said when I asked her to describe how to handle a scenario in which a hunter and a vegan walk into a gym. For her, living here in downeast Maine, this is a weekly reality, not an imaginary scene!

Her new book, “The Solutionary Way," lays out a systemic approach to problem solving that is a great fit for the wicked challenges of today’s world, including food debates. I particularly love her focus on progress-making as a practice and mindset. A lot of problems are posed fitting upwards of 9 billion people on a finite planet, but if even a fraction of those humans become humane solutionaries, I see a bright future ahead.

Zoe Weil on Forging “Solutionary” Paths to Progress

Meat tradeoffs abound

About five minutes after I posted, I noticed via the invaluable X feed of food journalist Tamar Haspel that

just published an incredibly useful post on Our World In Data that is directly related to this piece:What are the trade-offs between animal welfare and the environmental impact of meat?

Here’s a snippet:

It’s tempting to assume that what’s good for the planet is also good for the animal, but unfortunately, this is not the case. These two goals are often in conflict. What’s better for animal welfare is often worse for the environment, and vice versa. This is true across different types of livestock (for example, beef versus chicken) and across different ways of raising a specific animal (caged versus free-range hens).

This trade-off is easily missed. How consumers navigate this dilemma will depend on their values and priorities, including other things such as cost, taste, and their relationship with farmers and communities.

I came from a very "meart and potatoes " culture and only now begin to change to a plant.based preference because of information all around me, And --oh! those veggies in all their beautiful colors and tastes! Thanks for all the information you provide to those of us lost ouat there in cow- land.

Thanks so much for publishing this Andy. I really appreciated Hannah Ritchie's post. There's an obvious choice of course: eating a vegan diet is one of the most powerful choices we can make for the environment AND for animals. The choice doesn't have to be which animals to eat, but whether to eat them at all. In general, the lower we eat on the food chain the better for everyone (including our own health). Win, win, win :)