How to Navigate Stormy, Overheated Times

I was invited to give the 2021 Commencement Address at Warren Wilson College and, of course, it ended up virtual. The school is an innovative learning and doing hub bridging academia with issues and culture in the Appalachians. Here’s what I said. No matter where you are, and what stage of life you are in, I hope you might find an idea or practice or two worth considering or sharing.

What a moment this is. You face a disrupted landscape of change like nothing I’ve seen in my 65 years on this planet, 35 of which I’ve spent probing environmental problems and solutions as a journalist.

It can be paralytic and draining to confront a future that feels like you’re being forced to play speed chess while walking through a fog-cloaked maze of trip wires and landmines.

But I wake up each day hopeful and engaged, and I hope to convince you this is not wishful thinking.

First, wherever you are, whatever you’re doing, please stop and take a deep breath, then let it out. Then maybe one or two more. You’ve earned a breather. And there’s a long journey ahead.

To help, here’s an inspiring moment from my Sustain What webcast when Karen Alley, a hard-working young climate scientist at the University of Alberta, thrilled us with a hypnotic hammered dulcimer composition called “Into Open Air.”

I just love the reaction of the comedian Chuck Nice, who’s deeply focused on climate change, but also on the human connections that come through laughter.

These arts-focused Sunday shows are my soul boost after weekdays spent digging in on paths past the pandemic, on clean-energy policy, on disaster preparedness.

Karen Alley uses music to stay centered. I use music and community, and walks in the woods with my wife and our dogs. You know what soothes your spirit. Don’t lose that amid what feels like endless urgency — finding a job, staying safe, and all the rest.

Yes, on an even bigger scale, urgent work is required to address sustainability challenges. There, too, I recommend blending any sense of urgency with patience.

We’ve been in surge mode so far, going from 2.7 billion people when I was born in 1956 toward 8 billion people now, with the world population almost certainly hitting 9 billion by 2050.

Just in the last three decades, humans have emitted more than 800 billion tons of heat-trapping CO2 in the air — nearly 40 billion tons last year even with the great global slowdown from the pandemic.

That’s certainly not the kind of emergency brake we need.

But perhaps this Great Pause — as some have called this past year — offers your generation and everyone alive today a sense of what societal characteristics might produce a better human journey going forward.

Imagine an economy that truly, concretely, values the caregivers and maintainers in our lives, that values the makers and responders among us in ways that are missed in current economic models.

Imagine building a clean energy system that empowers lives and livelihoods from rural Appalachia to urbanizing Africa.

Imagine building a less polluted information system, one that makes the most of global Internet connectedness, transparency, and knowledge access while limiting toxic, dangerous polarization, hate and fakery. It’s doable, with urgency and patience.

One tip for sure. Don’t unplug. The world needs you online — not addicted, of course, but engaging constructively.

If you give up, the haters and disinformers will happily fill that space.

Think of it like a workout. A practice. Then turn it off for a bit. But when you see a novel species of insect, for example, rev up the phone and post the inspiring image on iNaturalist.

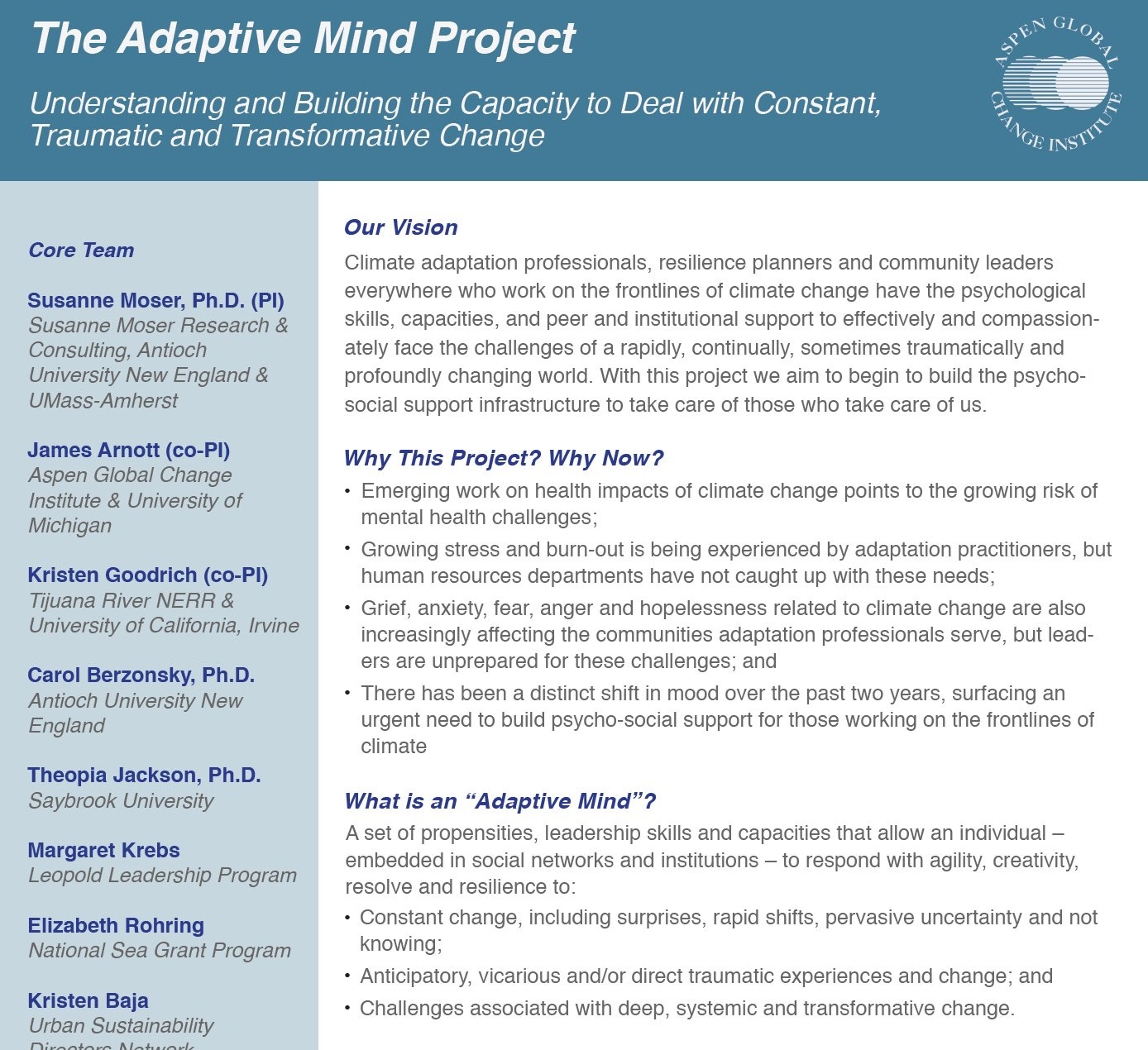

Here’s one more bit of imagining. Imagine the value of cultivating and spreading the capacity to have an “adaptive mind.”

To me this may be the single most important goal right now in a century of rapid change, layers of uncertainty and enormous consequence.

This is a concept championed by Susi Moser, a social scientist working to build resilient communities and policies in the face of climate change. But its value goes way beyond climate.

Susi says an adaptive mind is a set of traits, leadership skills and capacities that allow an individual — embedded in social networks and institutions — to respond with agility, creativity, resolve and resilience…and to do so when facing pervasive uncertainty, traumatic experiences, or anticipation of them, and challenges associated with deep, systemic and transformative change.

Ponder those words and think about the world around you. Seems like a pretty great fit.

Susi’s work is sufficiently important that I hope you’ll explore her ideas at this internet shortcut: j.mp/adaptivemindproject — no spaces.

So how do we get there?

The good news is that the Warren Wilson community is already on this journey.

When I visited your school in 2009 for a Headwaters environmental conference, I marveled at your living, working campus, with the productive farm and forests as important to the learning as the classrooms.

I loved how the focus on scientifically measured environmental performance, and performing arts, linked Warren Wilson with the wider Appalachian community.

I’ve tried to keep track since then, and was excited to see how the Appalachian Studies curriculum has further connected scholarship and rural society.

And now you’re among the leaders on the Top Sustainable Colleges list.

And in 2020 Warren Wilson not only fully divested from fossil fuels. The school also became a case study in responsible and productive investment in companies and funds building a better future.

Best of all, in almost every instance, students — you — have been leading these efforts.

And the work continues. Just last week, I visited Warren Wilson’s Facebook page and saw biology major Sophie Allen tackling plastic waste produced by the 3D printer in the Creative Technologies Lab.

We need creative technologies for sure, but also need to track what’s coming in and going out as we build the future.

Sophie’s automated spooling system may not save the planet on its own, but it’s a step in a great direction.

When tackling huge, systemic challenges like the global surge of plastic waste, or global warming, what’s needed is motivation, innovation, communication — and sustained assessment to know what’s working, or not.

I just want to leave you with a quick final set of tips I find useful when navigating complex challenges.

First, don’t wait for clarity!

Some of those listening now might have attended that Headwaters Gathering in 2009. If you were there, you probably heard a great take on acting amid uncertainty from one of the pioneers of ecological economics, Herman Daly.

As he put it, “When you jump out of an airplane, you need a crude parachute more than you need an accurate altimeter.”

In the context of the climate crisis, more than enough is known to act now to cut local vulnerability to today’s climate hazards while also pursuing global cuts in heat-trapping pollution.

Second, embrace diversity.

Americans, all too slowly, have begun the hard work of grappling with, and overcoming, centuries of aversion to racial diversity. I’m talking here about embracing a diversity of views and sources of expertise, as well.

One of my biggest mistakes in my 33 years of reporting on climate change was spending too much time talking to climate scientists. I love climate scientists. They’re amazing pioneers in a tough field and their work is incredibly interesting — taking me from the North Pole to the Amazon rain forest to supercomputer centers around the world.

But it took me until 2006, 18 years in, before I realized what I was missing. That’s when I first began interviewing social and behavioral scientists, asking them why we seemed so stuck.

They laid out a mountain of research I’d missed in my focus on melting glaciers and burning forests — research showing vividly why big risks can hide in plain sight, why we hadn’t really confronted climate change despite such clear evidence.

When you have time, go to the web shortcut j.mp/scariestscience to read an essay describing what I found in more detail. This science is indeed scary. But it’s invaluable, and points to powerful steps toward cooperation and action even amid disagreement.

Social and behavioral scientists still too rarely convene with what some call the “hard” sciences. The climate challenge can’t be tackled without both

That leads to my third point — composed of a single word: Listen.

Solutions emerge amid diversity and difference. A friend of mine at Columbia, a psychologist named Peter Coleman, runs a project called the Difficult Conversations Laboratory. I’d love to see one in every community on Earth.

A key tactic when looking for cooperation amid deep differences is listening.

And I mean really active listening, not the kind of impatient listening I and other reporters typically do, where we’re waiting for the perfect emotional quotable quote.

Or the kind of listening in conversations you know you’ve had where you’re really just waiting to make your point more than actively absorbing what the other person is saying or feeling.

This is a vital practice facing a problem as complex as climate change, in which we actually need what some ecologists call “response diversity.” We need edge pushers and group huggers.

Imagine how humanity would have fared tens of thousands of years ago if we had all hung back by the fire or all headed out over the next ridge. The world right now is too complex for one energy path.

So listen.

Sadly I can’t do that today, given this is a one-way talk. But please follow up with me at @revkin on Twitter or by email.

I’ll offer a final tip. Don’t discount love and faith.

Our challenges fitting humanity’s infinite aspirations on a finite planet and pursuing global wellbeing are delineated by data. The rate of warming, the loss of species, the level of poverty.

The menu of choices societies face can be expanded by science and technology. Genetically engineered foods could help end hunger. Safer small nuclear plant designs and battery breakthroughs could help slow warming.

But the choices we make will be shaped mainly by our values, not numbers.

By how much we value others — other people or other species — including generations yet to come.

And faith? I don’t mean religion, specifically. I mean faith in the potential goodness in every person. And the leap of faith that’s necessary in making a choice when facing big unknowns.

Don’t take my word for this.

In 2014, at the end of a weeklong scientific meeting at the Vatican on “Sustainable Humanity,” I turned to the legendary 96-year-old oceanographer Walter Munk. I asked, “What do you think it will take for humanity to have a smooth journey in this century?”

I kind of assumed he’d say something technological, about carbon capture or fusion power, or maybe political will.

His answer?

“This requires a miracle of love and unselfishness.” He told me.

He passed away at age 101 in 2019, but that vision will be with me the rest of my life.

Thank you, and here’s to a stirring and productive journey ahead for all.