How to Make A Difference Amid Extreme Floods and Droughts on a Human-Heated Planet

Some tips for seeking sanity and impact amid nonstop waves of dire events and hot headlines

Watch my Sustain What webcast on dry and wet extremes and the media.

As the Horn of Africa faces rising famine risk fueled by the most protracted drought in many decades and spiking food prices, 2,000 miles across the western Indian Ocean, a third of Pakistan is inundated by what leaders there are calling a "climate catastrophe" after eight unrelenting weeks of monsoon rains in unthinkable volumes. Here's drone video from a government rescue effort tweeted by Pakistan's minister of climate change, Sherry Rehman on August 29.

And of course Pakistan, along with India, had just endured a record-breaking spring extreme heat wave that prompted comparisons to the apocalyptic opening scene of Kim Stanley Robinson's latest cli-fi novel, set in a South Asia gripped by deadly humid heat.

Such is life (and sadly occasionally death) on a planet experiencing both weather whiplash in particular regions (Californians know this all too well) and simultaneous interconnected crises in aggregate (Vladimir Putin's war on Ukraine is also a war on the poor in Africa and the Middle East facing hunger and energy poverty).

There's a fractal aspect to this, with world news and national news having the same feeling. Consider U.S. headlines of late on catastrophic flash flooding in Kentucky, Missouri and Illinois against the persistent intense drought in the West.

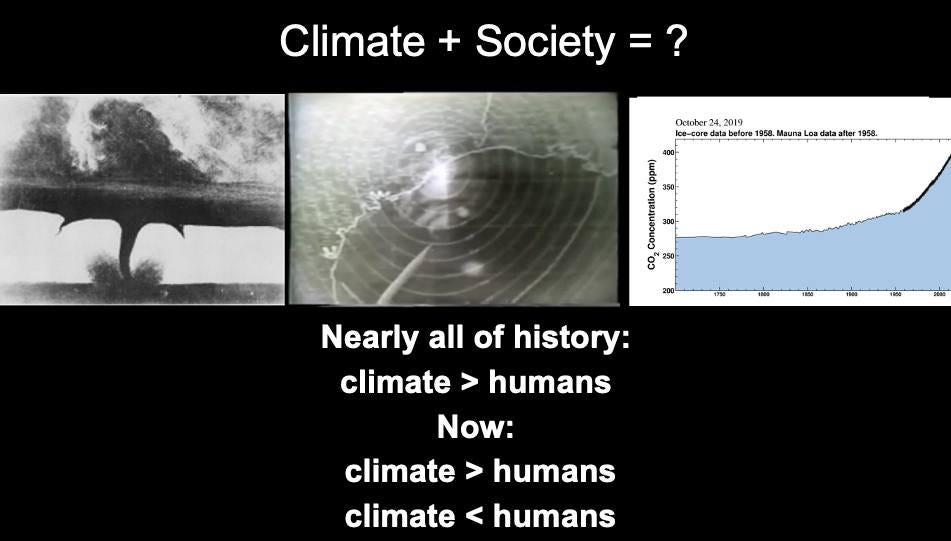

This current spasm is just that latest instance of the news cycle featuring nonstop, multiple, overlapping crises related to humanity's increasingly two-way relationship with the climate system:

We're jolting the climate through the buildup of planet-heating greenhouse gases that can intensify deluges, heat and drought.

The system, in return, is jolting us as communities grow and spread in today's climate danger zones, like the flood-prone watersheds of Pakistan and the drought-prone Horn of Africa.

As a result, the climate crisis is about far more than global warming. Recent science shows people are moving into flood danger zones far faster than climate is changing, drawn by commerce or productive soils or pushed by poverty or prejudice.

Here's a funky illustration I made after writing an illustrated book on humanity's weather and climate learning journey with my wife, Lisa Mechaley:

What do you do facing this maelstrom - as a leader, a voter, a news consumer and social-media sharer?

For your own sake, filter your input

For your friends' sake, filter your output

For the planet's sake, apply your talents

Let's go deeper on each.

Filter your input

Garbage in

Remember, the programmers who build the platforms we rely on to track events, seek information and find each other designed them mainly to suck us in and pull us down - with feeds filled with a tuned mix of imagery or posts designed to validate or aggravate more than inform. Add to that the news media's need for your attention (yes, including me) just for a moment. The result can be overload and disengagement just when the opposite is needed.

It's easy to be overwhelmed, needless to say. Ask yourself a key question: is this information useful to me?

Every day I try to heed the great advice offered early in the pandemic by Jeff Schlegelmilch, the director of Columbia's National Center for Disaster Preparedness. Become your own information filter. He was talking about people facing big decisions in emergency management organizations but I sense his words resonate for anyone!

Here's Schlegelmilch making this point in an early Sustain What conversation (also with the writer Meehan Crist):

Don't be distracted by blame games

After 35 years of writing in depth on climate change, to me one of the least useful debates is over how much of some extreme weather event is from global warming. That's an important scientific question. But despite perceptions and spin, disasters on the ground are still nearly all the result of actions, or inaction, on the ground, not (yet) some human-altered dynamic in the atmosphere.

It's worth recalling that, overall, weather-related deaths have declined dramatically, as the World Meteorological Organization summarized last year. And do read University of Colorado climate-policy researcher Roger Pielke Jr.'s series of posts on "what the media won't tell you" about floods, drought, hurricanes and more. As a member of the media, I agree with much of what he lays out.

Environmentalists, helped by some scientists, are pursuing legal strategies aiming to link attribution of some portion of some extreme events to emissions from fossil fuels. I'd suggest leaving that to the lawyers (or dive in and read about this, including the test case of a Peruvian farmer battling a German power provider, in Lancet Planetary Health and Carbon Brief. Also listen to the Defending the Planet podcast).

Climate change from burning fossil is almost implicitly part of every weather event, extreme or not, given the physics of greenhouse gases. That goes for Pakistan, the Horn of Africa drought, today's beautiful weather here in Maine after a storm, the sleepy start to the hurricane season. Its significance relative to other drivers of weather dynamics and societal losses is what remains hard to measure.

Pakistan’s trauma

Events in Pakistan perfectly illustrate what a confounding stew of risk humans have created.

Seth Borenstein and Sibi Arasu of the Associated Press have an excellent story up providing detail on the possible role of human-driven climate change, but also note the country's past history of devastating monsoon impacts and how generations of policies, from colonial times to recent days, have boosted vulnerability to floodwaters.

Reporting for the Third Pole, a journalism project focused on climate in South Asia, Zulfiqar Kunbhar has filed a compelling story on agricultural impacts of the inundation that will play out for many months to come.

In awful events like those unfolding in that country, it's vital to ramp up your skepticism when listening to politicians. On Tuesday, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif said something patently false: “We are suffering from it but it is not our fault at all.” [It's also vital for the media to avoid serving as stenographers in such instances and fact check such statements.]

They cite Abid Qaiyum Suleri, executive director of the Sustainable Development Policy Institute and a member of Pakistan’s Climate Change Council, who laid out another factor behind the devastation and dislocation that followers of my work will recognize:

Pakistan saw similar flooding and devastation in 2010 that killed nearly 2,000 people. But the government didn’t implement plans to prevent future flooding by preventing construction and homes in flood prone areas and river beds.

Also read every word of the compelling new analysis by Bloomberg Opinion's David Fickling: "Pakistan Could Have Averted Its Climate Catastrophe."

Here's one section that illustrates how vulnerable infrastructure and growing exposure to hazards set up a worst-case calamity even before coupled with climate change:

The Tarbela and Mangla reservoirs on either side of Islamabad have become so choked with silt sweeping down from the Himalayas that they’re losing their ability to swallow up floodwaters and prevent inundation further downstream. Just 57% of Tarbela’s storage capacity is now available, and increased silting may clog it altogether, a government committee was told earlier this month.

The underinvestment that has led to this state of affairs is chronic. Among the world’s top 20 economies by population, only Egypt has a lower rate of gross capital formation than Pakistan — a sign of a country that’s unable to build the infrastructure it needs to support a growing population. With the costs of climate impacts rising, more and more money is going to be spent not on the long-term investments needed to protect the country against future natural disasters, but simply on the clean up and compensating for the loss of productivity following catastrophes.

It's worth pointing out that the population of Pakistan vaulted from 44 million in 1960 to 225 million today - that's part of the expanding bull's eye phenomenon geographers have warned about for many years looking at every kind of potential disaster. As I wrote last December, the "P" word - population - still matters in gauging and responding to climate risk.

But the most important factor in the equation for climate risk is vulnerability. if 8 billion people on the planet were well housed, well informed and adaptable, we wouldn't be having this discussion. That's why my prime focus remains addressing the deadly vulnerability emergency (and opportunities) hiding behind the vague, even paralytic, dimensions of a phrase like "climate emergency."

Filter your output

Take a moment to ponder the real complexity out there before hitting [return] on a provocative tweet or post. Test that news item for reliability. Go one step beyond the headline. Do my "backtrack" exercise if you have time (to check where something crossing your screen came from). Check for other analysis from credible sources.

Try to recall Jeff Schlegelmilch's advice as an information disseminator. Are you just adding to the flood? I try to avoid this here, although I don't always succeed. Let me know what you don't want from me.

For the planet's sake, apply your talents

In 2017, I wrote an essay published in two magazines, Issues in Science & Technology and Creative Nonfiction, on lessons learned 30 years into my climate reporting journey. One big one?

The prismatic complexity of climate change is what makes it so challenging to address, but this also means everyone can have a role in charting a smoother human journey. I’ve come to see the diversity of human temperaments and societal models and environmental circumstances and skills as kind of perfect for the task at hand. We need edge pushers and group huggers, faith and science, and—more than anything—dialogue and effort to find room for agreement even when there are substantial differences.

Mix what you love with what is needed

If you're young, you can consider shaping your career path to reduce risk for those most in need (in engineering, business, the arts, you name it). This can happen even if you're older. My friend Nathanael Johnson grew tired of reporting about climate and food risks and the energy transition and is becoming an electrician to help actualize the transition. Listen to our conversation earlier this year.

The landscape artist Stacy Levy has created pieces that actively help clean up environmental damage. Her Spiral Wetland, a living botanical sculpture, soaks up excess nutrients in waterways while echoing the famed 1970 stone Spiral Jetty Robert Smithson built in the now-shriveling Great Salt Lake.

I'd love to hear about other examples of this sort.

Help your community

Everyone on the planet can help do one thing that can make a difference - work to undertake a community vulnerability shakeout. There are links and videos in this post that can help:

Support critical government policies and projects

Setting aside blame disputes over which countries owe which for global warming impacts (this'll be an endlessly divisive, even impossible, task), there is a powerful, even self-serving, argument for the world's powers - and yes the United States still leads the pack - to do the same kind of vulnerability assessment we can all do at home and invest for resilience where the need is greatest.

Many lawmakers have pulled back from this. That's a big mistake.

Much of the World Food Program effort to get wheat from Ukraine to the Horn of Africa in recent weeks was under United States funding. On Tuesday, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken noted, "The United States is the largest contributor to the WFP, having provided $5.7 billion to the organization since October 2021. Since February, the United States has provided over $5.4 billion in humanitarian assistance to scale up emergency food security operations in food insecure countries globally."

Of course, this is vital responsiveness, not vital prevention.

The Famine Early Warning System Network, FEWSNET, an essential effort aimed at heading off food catastrophes before they strike, was founded by the United States Agency for International Development in 1985. Its Horn of Africa forecasts remain dire through September. Scientists tracking the enduring Pacific pattern La Nina see big warning signs that a fifth season of rains will not happen next spring.

From fragility to resilience

One critical step is fully integrating climate analysis into strategies through which the United States and allies can foster sustainable and just advancement in "fragile states."

Watch the Sustain What episode I did on this theme for starters: "Can the U.S. Go From Responding to Fragility to Spreading Resilience?"

At one point Matthew Barlow, an extreme-event scientist at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, stated the key point straight out: "If you want a successful security strategy the climate piece has to be front and center."

It was notable and jarring that his own phone severe-weather app buzzed as he was speaking. Listen and watch!

I encourage you to watch and share the full episode, which also featured Mickey Glantz, a longtime expert on climate impacts in developing countries; Linda Robinson, a Rand Corporation security analyst and Rod Schoonover, a former U.S. intelligence officer focused on climate. On a previous webcast he noted ruefully how such threats too often sit on page 21 of risk roundups.)

In gauging the horrific monsoon impacts in Pakistan, I encourage you to click back to the work of Beth Tellman and colleagues, who last year charted how, around the world, people are moving into zones of inherent flood danger faster than any known change in the dynamics of flood events from global warming.

Postscript

That second grain-carrying ship I wrote about, the Brave Commander, arrived in Djibouti as the week began and disgorged more than 23,000 tons of wheat that, the World Food Program estimates, will feed 1.5 million people for one month in Ethiopia.

That's both a wonderful small step and a sign of how important it is to end the Russian war on Ukraine and work to foster human welfare for the long haul.