I was pleased to see

, a fine journalist unafraid of complexity, serve as an advice giver on the latest episode of podcast on Substack. We live in a society and discourse full of fault lines and land mines and the brittleness of online media, in particular, make it ever harder to find common ground amid differences.The episode - a conversation with Ripley,

, and The Disagreement co-founder - focused on how to disagree on Gaza with friends and family. My wife and I just this morning had an intense discussion with one son whose views on Israel have swung sharply from October 7 to now. Please watch and sign up for the journey ahead.In a yes-no world, complicate your narratives

Ripley has been a guest on a couple of my webcasts on polarization and conflict, including a particularly great one in 2021 (I’m adding a vital excerpt below):

But I’ve been a fan since 2018, when the Solutions Journalism Network commissioned her to write Complicating the Narratives, a pivotal report on how to cover conflict constructively. It was aimed at journalists but the findings are useful for anyone trying to navigate amid the contention around our toughest issues - race, climate, Middle East, onward. Here’s a snippet:

I spent the past three months interviewing people who know conflict intimately and have developed creative ways of navigating it. I met psychologists, mediators, lawyers, rabbis and other people who know how to disrupt toxic narratives and get people to reveal deeper truths. They do it every day — with livid spouses, feuding business partners, spiteful neighbors. They have learned how to get people to open up to new ideas, rather than closing down in judgment and indignation.

I’m embarrassed to admit this, but I’ve been a journalist for over 20 years, writing books and articles for Time, the Atlantic, the Wall Street Journal and all kinds of places, and I did not know these lessons. After spending more than 50 hours in training for various forms of dispute resolution, I realized that I’ve overestimated my ability to quickly understand what drives people to do what they do. I have overvalued reasoning in myself and others and undervalued pride, fear and the need to belong. I’ve been operating like an economist, in other words — an economist from the 1960s.

For decades, economists assumed that human beings were reasonable actors, operating in a rational world. When people made mistakes in free markets, rational behavior would, it was assumed, generally prevail. Then, in the 1970s, psychologists like Daniel Kahneman began to challenge those assumptions. Their experiments showed that humans are subject to all manner of biases and illusions.

“We are influenced by completely automatic things that we have no control over, and we don’t know we’re doing it,” as Kahneman put it. The good news was that these irrational behaviors are also highly predictable. So economists have gradually adjusted their models to account for these systematic human quirks.

Journalism has yet to undergo this awakening. We like to think of ourselves as objective seekers of truth. Which is why most of us have simply doubled down in recent years, continuing to do more of the same kind of journalism, despite mounting evidence that we are not having the impact we once had. We continue to collect facts and capture quotes as if we are operating in a linear world.

But it’s becoming clear that we cannot FOIA our way out of this problem. If we want to learn the truth, we have to find new ways to listen. If we want our best work to have consequences, we have to be heard. “Anyone who values truth,” social psychologist Jonathan Haidt wrote in The Righteous Mind, “should stop worshipping reason.”

We need to find ways to help our audiences leave their foxholes and consider new ideas. So we have a responsibility to use all the tools we can find — including the lessons of psychology.

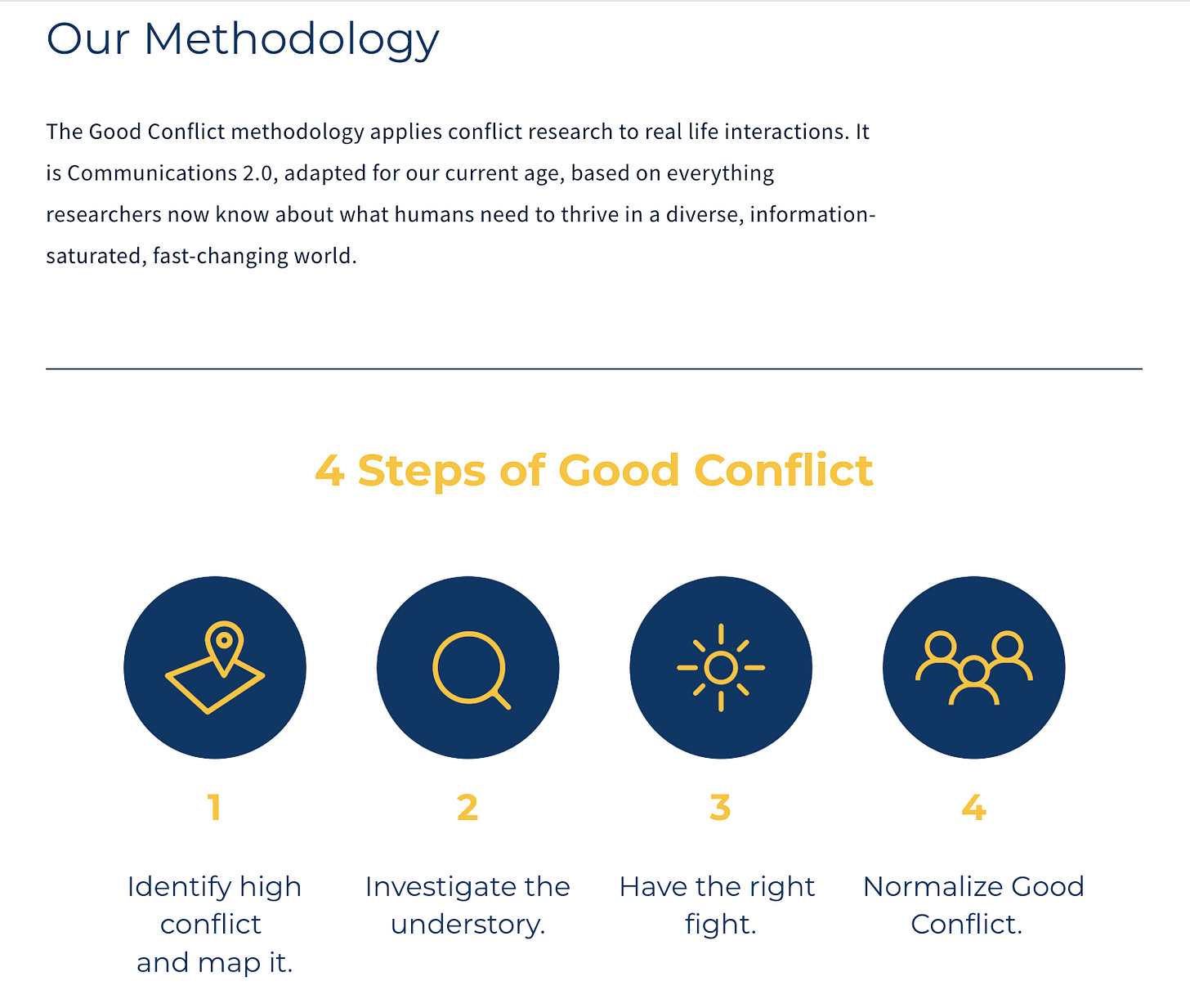

She ticks down a host of techniques, with “looping” a key practice (listening, distilling, repeating what you hear, and asking for more) that was also discussed on The Disagreement. Luckily Ripley and a partner have built a consultancy, Good Conflict, that can take you or your organization deeper.

Create space for constructive disagreement

In that 2021 conversation with Ripley, another guest, my dear friend Reggie Harris, a longtime folk singer who I call a “civility activist,” vividly illustrated a key need - to create space for constructive disagreement in the heat of the moment.

Amid the turmoil of the pandemic and George Floyd activism, Harris had attended a Black Lives Matter rally in rural upstate New York, and a simultaneous MAGA rally complicated the situation (context).

“My name is Reggie”

Here’s the transcript of Reggie’s story:

One of our people had gone down, one of the young women had gone down, and talked to the Trump people. And she came back and she just said, we have to try to talk to them. And on that day, I didn't really feel like engaging.

I just wanted to be a presence. But this guy kept yelling and I finally said to myself, engage. So I walked over to him and I just said, you know, so what's this about $5 a gallon? And he looked at me and he said, you don't belong over here. You stay over there.

You guys, we're keeping our distance. We're being respectful. And I said, I don't want to stay over there. I want to talk to you. And so we began talking about the gas prices and a couple of other things. And then he said a couple of things. I said a couple of things. And soon it was escalating.

And some of my friends who were there also started to escalate. And so I asked them just to leave us alone. And I continued. Well, at one point, he and I were on some point and just going at it. And I just could feel myself completely losing control.

And I thought, this is not why you came out here. And I couldn't figure out how to disengage because now we were in and there were a couple of his, you know, Trump-supporting friends who were nearby and they were sort of egging him on more. And finally, in the midst of one exchange, this wonderful thing happened.

I just said to him, ‘Hi, my name is Reggie.’ And he looked at me and he said, ‘What?’ And I said, ‘My name is Reggie.’ And he said, ‘Oh, I'm Ed.’ And I said, ‘Good to meet you, Ed.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, good to meet you too.”

And then that breath gave us an opportunity to sort of settle and then I said look you know I hear you. You were saying you're a veteran and you said you were a truck driver. I'm a musician. I travel around the country. We're probably buying gas at the same rate and he said yeah that's probably true. And so we started talking about gas prices and having to keep our vehicles fueled and it gave us some place to go and then the other folks fell away and we actually talked for a half an hour and now each of us were trying to find points to agree on.

And it was hard. But I finally said to him, look, I know that whatever I say here to you today is not going to change how you vote or maybe even how you think. But at least, and he said, yeah, at least we're talking to each other. And I said, maybe the next time we meet - it's a small community in the supermarket or wherever - we can just say hi and start from a different place.

Related shows:

A Reminder that Israelis and Palestinians Can Forge Paths to Peace

Watch my Sustain What discussion of pathways to eventual coexistence, with Palestinian peace builder Aziz Abu Sarah, “difficult conversations” researcher Peter Coleman and Mira Sucharov, an expert on Israeli/Palestinian politics and culture on YouTube

Pádraig Ó Tuama & Friends on Language as a Conflict Trap or Peace Pathway

This was the second episode in my Watchwords series - exploring words that confuse more than clarify and how to shift dialogue from divisive traps to open vistas offering routes out of conflict.

We centered on the arts and practices of special guest Pádraig Ó Tuama, a poet, theologian, mediator, On Being podcaster and more.

He was residence at Columbia University that year, working with psychologist and "Difficult Conversations” Lab founder Peter Coleman to examine the language of peace. Learn more below. Here's Ó Tuama's website: https://www.padraigotuama.com.

Two more guests joined this conversation: Irene O’Garden – A poet, educator and author, most recently, of the book of essays “Glad to Be Human”; and Reggie Harris.

Here's info on the Columbia "Peace Speech" project. With support from the Morton Deutsch International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution (MD-ICCCR), Teachers College, and the Climate School at Columbia University, Coleman and Ó Tuama are teaming up to explore the power of language when it comes to promoting peace, security, and sustainability across the globe.

Here’s a farewell call to action from Reggie Harris: