How Agencies and Communities Facing Wildfire and Other Climate-Linked Hazards Can Collaborate to Cut Risk Now

I talk with two leaders of the Biden administration's effort to fight fire before things burn. A question on the floor: Will we someday thank first preventers along with first responders?

Please SUBSCRIBE to receive my posts by email.

This 2022 post has more relevance than ever because of the 2025 fire catastrophe around Los Angeles and the re-election of FEMA-hating President Trump. You might also want to watch my 2018 Aspen Ideas Festival conversation with Trump’s first FEMA chief, Brock Long.

The latest news-making wildfire, named the NCAR Fire for the National Center for Atmospheric Research near where it was sparked on March 26 in Boulder, Colorado, ended up burning out safely. It may even have acted as a small unplanned "prescribed burn," cutting combustibility ahead of the hotter fire season to come.

But the blaze serves as a reminder that communities built in ecosystems prone to fire in a human-heated climate have to be vigilant and proactive. "Should an ignition have occurred [in] exactly the same place during one of Boulder's infamous downslope windstorms, it could have been a catastrophic event," tweeted Daniel Swain, an expert in Western wildfire at the University of California, Los Angeles, and NCAR's Center for Climate & Weather Extremes.

Just three months ago, Boulder County saw a thousand homes and businesses, most in urban and suburban settings thought safe, destroyed in the drought- and wind-driven Marshall Fire.

To explore pathways to proactive risk reduction in such regions, I took my first work trip in nearly two and half years last week. I was invited to run my Sustain What webcast from the headquarters of the Federal Emergency Management Agency in Washington, D.C.

I sat down there with Deanne Criswell, the administrator of FEMA - with decades of experience in firefighting and emergency management starting in the Colorado Air National Guard - and Lori Moore Merrell, the administrator of the U.S. Fire Administration, who has similarly deep roots in firefighting in Memphis, Tenn., combined with a doctorate melding public health and data science in pursuit of more effective fire prevention and response.

Here's the video, which you can also watch and share on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter. Below you can explore a transcript, with some cleaning up and editing for clarity.

Our discussion was premised on the reality that accumulating heat-trapping greenhouse gases from human activities, mainly burning fossil fuels, has set in motion many decades of global warming and regional climate disruption.

Cutting planet-heating pollution is vital and can cut odds of worst-case outcomes. But as the U.N. climate panel recently reaffirmed, even if the world somehow got on a Paris Agreement path for emissions that wouldn't significantly alter patterns of damage from severe weather for decades. The prime reason? In far too many communities facing a host of climate-related hazards, people are still building an "expanding bull's eye" in danger zones. (For more on that concept, track the work of Walker Ashley and Stephen Strader, who are measuring such bulls' eyes nationwide).

This Twitter thread I posted ahead of our chat lays out the basic questions we explored.

Where combustibility and community meet

Andy Revkin - I've been on the climate beat since the 1980s, and one thing I've learned through that whole process is I was focused too often on climate change and not focused enough on community change.

We live in a landscape where we can be less or more vulnerable to the changes around us - the hazards in the system. Grasslands and forests burn. But when they jump into an urban area, the fuels that are combusted are homes and gasoline in car tanks, and that becomes a new kind of a hazard. So in that landscape of change - with changing climate and changing communities - the key questions are what do we do on the ground even as we work to cut the the pace of global warming?

It's great to be here with both of you this morning. And it's an honor, really, because you both represent a rare commodity. You're systems thinkers and systems doers. You also have been grounded in practice. You both have worked in firefighting and now in administration. I wanted to start with the key question, which is how you became you - so far. And we'll start with Administrator Criswell.

Deanne Criswell - I started out as a firefighter in the Colorado Air National Guard, and then I became a firefighter for the City of Aurora in Colorado. And that really cemented my passion for public service and always wanting to be part of something that was helping communities. As I continued through both of those careers, I was always looking for opportunities to grow professionally, to stretch myself outside of my comfort zone. When the emergency management position became available within the Aurora Fire Department, I applied for that and that kind of gave me my taste of an emergency management career and what the potential could be. It really inspired me to want to learn more about not just the response piece, but this overall part of how do you help people before disasters and how do you make sure that your communities are more resilient and more prepared to withstand the events that they might be facing. So I followed that up by coming to FEMA the first time, and I worked as a federal coordinating officer as an incident management team lead.

I spent a couple of years in the private sector and then I had an incredible opportunity to go serve as the Commissioner for Emergency Management in New York City, which was from 2019 until right before I came here. And the majority of that was managing the COVID-19 response for the city and bringing all the right leaders together. And I think it was [because of] that experience that I was called by the [Biden] transition team to lead FEMA again from the top position.

Andy Revkin - And when you think back to the on-the-ground work in Colorado now in this administrative leadership role, what is the way you can create possibilities on the ground back in areas where firefighters are often reacting to fires that start that could have been prevented. How do you make the link between your decisions now and this landscape across America and across the world of combustibility and community?

Deanne Criswell - I think my experience on the ground was essential to help inform my vision for how I want the agency to support communities - having been that person who was responding to disasters and helping my community be more resilient and prepare for disasters and trying to figure out what other resources are available to help me - what kind of assistance, what kind of resources come from the federal government or from the state to ensure that our communities are taking the necessary steps so they can be better prepared.

So I think that really has driven where I've been coming from in this role of understanding what it was like to be that responder. We say all the time that disasters start end at the local level. That is so true. So what we need to do is a federal agency is never forget that and that we're always putting herself in their shoes and trying to figure out how do we help them help themselves so they can be more resilient.

Andy Revkin - And Dr. Moore Merrill, you also have roots in firefighting from way back in Memphis, Tennessee. Then you dove into data science and public health. Public health is an arena where the same issues sit. In other words, what can you do proactively to prevent the need for all of that response? It must drive you a little crazy sometimes, when you see how we have a hard time as communities with getting ahead of the game, including with investments like the federal firefighting budget for wildfire is so much bigger than the prevention budget. But that's just a function of how humans think and react. Could you give a little snapshot of your journey from Memphis firefighting to what you're doing now and tell folks a little bit about the Fire Administration?

Lori Moore Merrell - Very much like the administrator of FEMA, I started in the fire service, as well, and spent seven years in Memphis Fire in the late '80s, early '90s before being recruited to the International Association of Fire Fighters, which is the labor union that represents firefighters throughout the U.S. And in that opportunity, I continued with my education, and that's when I got really heavily into public health and data science and performance metrics - epidemiology and really being able to look at system capabilities and local-level response capabilities.

I conducted a lot of research through my time with the IAFF, looking at local resources and their capabilities and capacity to respond, not just to day-to-day emergencies, but the surge capacity that they have when we have these disasters that occur.

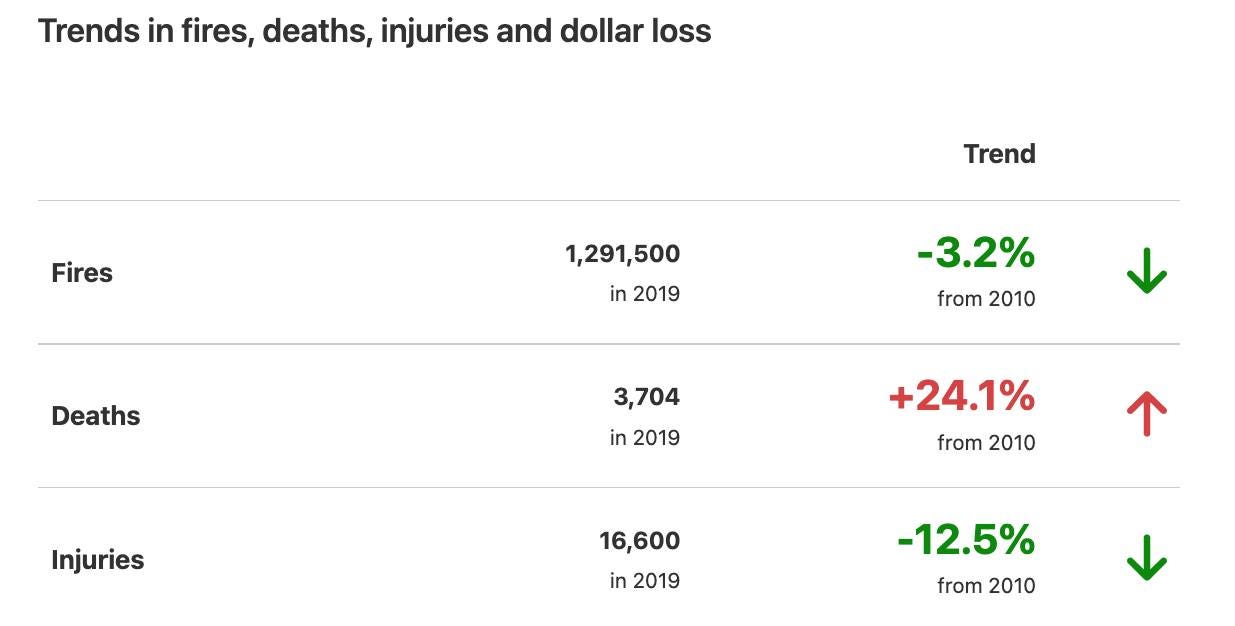

Data, as you know, informs everything today. The problem is getting people to listen and not be reactive, to be much more proactive. To look at what the data are telling us and be able to plan ahead for those kinds of circumstances that we know are inevitably going to occur. And so the United States Fire Administration was actually created in 1974 by the Fire Prevention and Control Act to train, strengthen and support our fire service capabilities to respond, but also expanding into a National Fire Academy for those capabilities, a national data center. Data are going to speak to us. They will be able to tell us if we can have the appropriate metrics for that kind of information, then the path we need to follow becomes much clearer. It's a matter of getting people to pay attention and listen along the way.

Andy Revkin - Yes, the gap between data and decisions across all the risks I've reported on for three decades seems to be still the biggest challenge. As a journalist, I was biased to thinking telling a better story, getting it on the cover of Discover magazine or the front page of The New York Times would be the way forward. The more I've watched how things play out, the more I realized that path doesn't really work. Saying this is important has limits, as opposed to enabling communities to find their own path, especially in something like wildfire.

That circles back to what we were saying about the lessons you [administrator Criswell) learned in your early days locally in Colorado. We'll talk about Colorado as a case study. The Marshall Fire in Boulder County was so horrific. It started out in a climate-sparked grassland landscape. But then it jumped into town.

Where do we go from here? And this also gets to this other question you both face, which is, there's that moment when there is the calamity and everyone pays attention, and then most of the world goes back to business, even while Bowling Green deals with rebuilding after tornadoes, or now New Orleans, or Superior, Colorado [with the fire]. How do you engage with communities to sort of build forward better?

Deanne Criswell The Marshall Fire was devastating. We've heard people talk about it as a wildland fire or the urban interface, but it really wasn't. It was a suburban community, a suburban neighborhood. When you talked about the climate nexus in the beginning, it was a severe drought. They hadn't had rain in many months, much longer than expected, and then combine that with some high winds and then a spark that turned into this grass fire.

And then the homes became the fuel and it turned into this conflagration. It grew so rapidly. When I was talking to families about their evacuation, they were saying how they had to drive through their neighbors' lawns to get out. One of the things that I worry the most about is these types of events are continuing to intensify really rapidly, which means we have less time to properly warn, less time for people to act.

How do we make sure that we can continue to warn as far in advance as we can, but also make sure that people have the means to get out of harm's way as quickly as they can? And I'll pivot that a little bit to one of the biggest things that we can do as a nation, whether it's a wildfire or any natural hazard. It is to make sure that we have strong building codes.

Building codes are going to make sure that we have enough time to warn people; we have enough mechanisms in place to protect people so they can get their families safe; they can get out of harm's way. Yet so few communities across the country have adopted the latest building code standards. As we continue to rebuild communities, we need to make sure that we're building them to be more resilient for the future, that we're using the latest building codes that are out there, that are designed to protect these communities, designed to protect these families and make sure that we incentivize that and provide examples of where it's worked.

Responding to places after Hurricane Ida last year, as well, we could see communities that had rebuilt from previous disasters to the most current building code had very little damage. But other communities that maybe hadn't had the opportunity because they didn't need to rebuild suffered more.

That just really goes to show how important it is and what a difference it makes to have those building codes in place. You're not going to stop these events right now, right? As you said, how do we get communities to think differently and help them understand what their threats are today, what their future threats are going to be, put the right codes and standards in place to protect them better.

Andy Revkin Thinking about your use of data, FEMA has these risk maps. The vulnerability map is really a useful part of that data output. Is there a way to get that to communities as they grapple with their zoning or their building codes?

Lori Moore Merrell - When we begin to put those two data sources together [on hazards and vulnerability] thats where we find we're able to mine that data for intelligence. That's where we get to be forward thinking because we already know we've got vulnerability for people who perhaps don't have the means to self evacuate because they're poor, right? Or they don't have the means to recover like their better-off counterparts in the same communities.

And so those are the kinds of things that the data will help us inform. The key here is when we know the information about the fire-prone areas.

"The event that doesn't happen is the best one"

The event that doesn't happen is the best one, right? Unfortunately, we don't get to have that a lot.

We need to work toward that. Prevention is absolutely key. It's not just the building codes; it's understanding the location of your home. When we say building codes, people often think about, you know, structural materials, which is important. But it has everything to do with your location, your landscaping, how close you're putting your structure to someone else's structure, your fencing.

All of those things matter because as you just alluded to in the Marshall Fire. What we saw was a grass fire that fed to this house to house, ember to ember fire. And it would skip over some houses that had better roofing materials, perhaps? So we know the things that matter within our codes and standards. We know the data has told us this.

What we need are decision makers to step up and put in the enforcement capability for codes that do exist and pass codes that don't exist, and then have the capability to withstand and hold true to those because we know what works. And we're at that point right now.

You mentioned me being frustrated. I do get frustrated with this because this is not, to use the proverbial phrase, rocket science. We know what works. What we need is to overcome the indifference and the complacency to have these measures put in place and then enforced.

Andy Revkin - There's still this landscape in America that makes this so problematic. I live in the Hudson Valley in a village, within a town, within a county, within a state, within a country. And even that village has some different standards - not related to fire - than the town that it's in. There's fire department sharing. It still seems to come down to these local issues.

Boulder County had fire codes, wildfire codes, but the cities within Boulder County are exempt because they are cities. And that's where the combustion turned into these disasters. So there's a lot of work to be done, I guess. And this gets me to my next question for each of you in the context of where we are right now with these layers of risk. You've got fire, you've got pandemic. In some places like California you've got earthquake and fire.

What keeps you up at night as either a glaring opportunity that people have not yet grasped on to or a real nightmare scenario?

FEMA administrator Criswell and President Joe Biden during a Hurricane Ida briefing (FEMA video)

Deanne Criswell - What's keeping me up at night or what I'm thinking a lot about right now is better understanding our future risk so we can be better prepared. It's so important for us to make sure people, individuals, communities, villages, towns, counties understand what their unique risk is, but not just based on a historical sense. We have to start thinking about the future risk because the disasters that we're seeing today are different than. They're going to be different than the ones we're going to see in 10 and 20 years. And so what keeps me up at night right now is how do we help communities better understand what their future risk is going to be so we can take action today to help reduce the impacts.

Andy Revkin - Who are the partners that need to be engaged for that? Who needs to be in the conversation to really make some progress in the next five or 10 years?

Lori Moore Merrell - Everybody from the federal government to our state, local tribal territorial partners, their decision makers. I think that we can learn from some of the the research that is ongoing. So our researchers have to be at the table. Private industry, who have their own research capabilities. I think the builders have got to be at the table. Our land management is going to be at the table.

We've got to have anybody with a valid data source who is bringing information because we don't know yet about the future risks that are impending without this kind of collaboration and data mining - and to be able to better inform us in how to be prepared.

So I think it's an all-hands approach, including the public.

We need them to pay attention to the lessons, to the messaging, and don't think that this can't happen to you. That's what we confront with fire often is that attitude of, you know, this, this can't happen to me. We need to overcome that indifference and complacency to say this can happen, and likely will if you're living in the interface environment right where we have said to you, first of all, we shouldn't be building there. But we continue to do that, unfortunately. We've got to understand the laws of nature because they are fixed and there are ramifications of not adhering to those laws.

Andy Revkin - One thing I've seen is this lack of transfer of wisdom that's gleaned when a disaster affects one community. Those around it don't always absorb the lessons. This transferal issue - learning from the community down the road that got sadly struck by a tornado or by the wildfires in Boulder, Colorado. That could have been Fort Collins. So how do we do the community-to-community thing? Does that feel like part of the landscape, too?

Lessons observed, but very few learned

Deanne Criswell - I think absolutely it is. This is a shared responsibility. This is shared between individuals, the communities, all levels of government, private sector, our nonprofit partners. We often have a lot of lessons observed, but very few lessons learned. We don't do a good job of really applying what we've learned.

When I think about the way people sometimes view my agency, FEMA, we think about the fundamentals of emergency management: we respond, we recover, then we mitigate. And I think we need to reverse that.

Mitigation needs to be up front with the preparedness side. We need to let people know what their potential risk is. As I talked about earlier, understanding your unique individual risk or the layers of risk so you can better prepare your families to protect them and so you can better mitigate the impacts. We have to shift a lot of our focus there. So we can we can see a change in the future.

FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell and New Jersey State Police Superintendent Colonel Patrick Callahan tour tornado damage in New Jersey from the remains of Hurricane Ida (New Jersey State Police / Tim Larsen)

Andy Revkin - I was writing about tornado losses and risk. I have for now for years. You have some great resources on building in tornado zones. The vulnerabilities are still huge in the South, particularly where there's been so much growth of manufactured homes and mobile homes. Is the same thing there yet for fire? A fire-safe menu somewhere people can find?

Deanne Criswell - We have ready.gov, which has so much information about the things that individuals can do to be better prepared, to understand what their risks are, to develop the plan to protect their families. But Lori and the USFA have done a lot of work specifically on the fire side.

Lori Moore Merrell - Yes, we collaborate with ready.gov but we also have fire-safe-specific messaging. We're trying to make sure it not only is in multiple languages, but also infographics. Those kinds of messaging tools we can use in every communication stream. One of the things we have to understand is that even in our fire-safe messaging we're also talking about safe and affordable housing, for example.

We are starting to focus at USFA on the enormous numbers of fire fatalities that have already happened this year, for example. You might be surprised to know that there's been 717 fire fatalities in this country since January 1st. This is not making the national media. This is the whole issue of equity. Our messaging has got to reach communities that are, you know, less fortunate.

When I have to make a decision between affordable housing and safe housing right then that's a problem. Making it safe by putting in sprinklers, smoke alarms, that drives up the cost. Now it's no longer affordable.

When that happens, then we have people moving into vacant buildings and then we have firefighters who are responding to fires from people who are trying to keep warm. And now I have three dead firefighters like in Baltimore because of a vacant-building collapse.

So this is a problem that is much deeper. When we talk about fire safety messaging and it's sort of taking it away from the [wildland-urban interface] WUI perspective, but it's a problem that spans the whole of our structural environment and our equity across this country.

A lot of our messaging is starting to focus on that because anybody who is going to listen to our fire safety messaging has probably already listened. So we have to change how we're doing it. We have to change the message itself to be much more applicable to people listening and taking action. We want the action. Don't just hear me. Let's act.

Making risk visible

Redfin's climate risk indicators for real estate

Andy Revkin - Something encouraging is that Redfin and other real estate listing websites now are adding flood risk. I think Redfin now has a climate impacts button. So as you're sifting for your next house, you now have information you might never have had before. It's information that is there - flood history and the like. But it's never been [visible.]. Are there other bright lights like that? And do you agree that that's good news?

Deanne Criswell - I'm excited and thrilled that we're seeing our realtors do this because it's important for you as a homeowner to understand what your risk is. So you know what you're going to have to do to protect your family. And so that is really exciting, and I think that there are other measures that we are taking here at FEMA.

You know, back on the equity standpoint of really trying to better understand where our underserved communities are so we can reach them and communicate with them directly. Understand what their barriers have been to accessing our programs, whether it's preparedness programs and mitigation programs or recovery programs afterwards. How do we understand what their barriers are so we can bring our services to them instead of trying to make them figure out how to navigate the federal bureaucracy to help protect and build resiliency within their communities.

So I see a lot of bright lights in the future as we really embark on this focus on building resilient communities and focus on place-based initiatives to help an entire community become more resilient instead of in the past, focusing on much more of an incremental approach to how we're trying to increase resilience. We have such an opportunity right now to do this from a community-wide perspective. And so it gives me a lot of hope, especially in the types of applications even that we've been getting for our mitigation programs that are really going to have community level impact.

Andy Revkin - As we were talking I was thinking about the energy arena, where we have the Energy Star label. Is there way to have a "Safety Star" when you're looking for a house?

Read about the FEMA Community Rating System

Deanne Criswell - I think one of the things that's out there is our community rating system, right? Communities can get rated to a different level that shows the amount of resiliency that they have. In fact, we just granted only the second community to reach a Level one rating, and that was Tulsa, Oklahoma.

That was a lot of deliberate commitment by the mayor to make sure that they were taking the steps that they needed to improve the resiliency of their community. Those types of things are really important, and they're going to see real significant impacts from that. They're going to see a decrease in flood insurance rates. They're going to see an increase in the resiliency of that community. That's one example, but I agree. I think that if we had something that was more widely known that people could make communities could really [say], Hey, this is the rating that we got or this is the level of protection that we have and that also drives people to want to build and develop in those areas.

Lori Moore Merrell - In the past and before I became the USFA administrator, one of the projects we worked on was looking at how well a community matches resources deployed to the risk environment. If those resources are matched well to the risk event to which they're responding, then that community is far less vulnerable to firefighter injury and death, civilian injury and death and property loss.

That is research that's been completed, that's been codified in our industry standards and the National Fire Protection Association standards. It's a matter of bringing that data to the table in order to have those kinds of grades codified and then performed or promoted out.

Andy Revkin - There's something else I want to get at, which I know you both care about deeply, which is the first responders. The impacts of all this on first responders of all kinds - their health and psychological sustainability. We're in this situation of nonstop change-driven events. Your website has resources. How important is that to getting us through this moment, assuming it's not an endless curve toward chaos?

Deanne Criswell - We have been asking so much of our emergency managers and our first responders lately, with the increase in the number of natural disaster events, but also these emerging threats that we're facing. You know, we're seeing our emergency management community respond and manage homeless crises or the opioid crisis. Then we threw COVID-19 on top of that. And so it takes a toll.

I think it's incredibly important for us as an industry - emergency management and first responders alike - to make sure that we are deliberate about our conversations about employees' mental health and wellbeing, as well as their physical health and wellbeing. And we have to de-stigmatize that conversation.

It's stressful. We deal with people at their worst time, and that can take a toll. We're working long hours with a really increased ops tempo that requires quick decision making that can have significant impacts on people's lives.

That's hard, and sometimes we need to just take a break. And so it's important to me that we make sure that we provide the space for our employees to feel like if they need time to recoup or reset that we give them that space. But we also give them the resources that they need in order to be able to continue to manage something like this. And I'm excited about one of the resources that we actually did just put out for all of our employees here at FEMA was the ability to use the Headspace app, and I've gotten so much feedback from our employees thanking us for doing that because it just gives them that opportunity to take a few minutes to reset helps them just keep that mental health, mental wellbeing and forefront, right? So they can continue to support the people that need our help.

Andy Revkin - I need that app. There's a comment that came in: "Good morning from the fire-prone, drought-stricken, colonized and occupied territories of the Serrano, Kitanemuk and other Indigenous peoples in the Mojave Desert of Southern California. Thank you for doing this."

This gets at this issue we've just touched on a little bit about inclusion. Native Americans face outsize risk in terms of wildfire. I was looking recently at a study showing that communities of color within this fire landscape have more exposure, more risk. So how do we address that? (The study concluded, "Affluent white people are more likely to live in fire-prone areas, but race and socioeconomic vulnerability can put minority communities at greater risk.")

Deanne Criswell - I think that there's so many of our communities that are built in areas that are more prone to risk. And when I first came in last year, I did a deliberate tour of the West and trying to understand some of the wildfire risk that we're seeing out there. And I did go and visit several tribes, in Idaho as well as in California, to better understand some of the needs that they're having or the barriers that they're facing. And I think that again, we have to better understand and reach out to the communities that we know are vulnerable, but perhaps don't have the resources or the capacity to access the programs that help them become more resilient.

We have a lot of work that we've done already, but we have more work that we need to do to engage with our communities and especially our tribal partners, to help them with the resources that they need to navigate our programs to help them become more resilient. But the other part that I thought was really fascinating is when I was visiting one of the things that I hadn't thought of that they reminded me of is [they said] we are also a resource to you. We know our lands better than you will know our lands. We have been here for many generations. And so we are a resource that you can rely on to help you better understand some of the techniques that you can use to help mitigate and prevent or then respond to some of these wildfire events. And so again, when I talked earlier, this is a shared responsibility and we have to make sure that we give a space for everybody to be part of that conversation.

Andy Revkin - There's this popular word these days - co-production of knowledge. It's making sure that it's two-way exchange among disciplines and and agency responsibilities and with communities. Columbia University recently did a three-year research project with an Inupiat community in the Arctic, where the risk is to their elders falling through the ice because the changing sea ice patterns with climate change are making it harder to hunt for seals. But the entire project was funded by the Moore Foundation as a relationship-building project. It's hard to do at the level of issues like fire safety, because you're talking about thousands of communities, but it seems essential.

Lori Moore Merrell - That concept is very much part of what we are talking about now with the transformational leadership. That theory says you bring everybody to the table because multiple skill sets can be leveraged against a problem, right? You know, before COVID, there wasn't a lot of collaboration with public health at the local level. And then when we needed to deliver vaccines, public health came to the fire service and said, you've got the standing army of available skill-ready people to deliver vaccines. And so that's what took place. Let's have this collaboration and discuss this problem and see if we can't come up with something together.

Andy Revkin - I just wrote yesterday about a new U.N. commitment to help better bridge the data-to-action gap globally. There are 2.6 billion people who still have no way of even getting a warning if there's a cyclone heading toward Mozambique or the like. There's tons of data. There isn't a ton of response.

[INSERT, 3/30: I misspoke above. Mozambique is one of the countries that does have an effective early warning system. See this tweet from Natalie Fiertz at the Stimson Center's Environmental Security Program and my reply.]

And there also needs to be more social science in the climate sphere. I had the conversation last year on innovation and climate, and a lot of it was about better solar panels. But there was a social scientist who had done a study of how little social science funding there has been to better understand how humans can respond to climate change. It's like a tiny fraction of our investment in understanding these problems has gone into understanding the human part of it. It feels like that gap needs to be filled pretty urgently.

Deanne Criswell - Every time many people hear the word innovation they immediately go to technology, they go to data. But innovation is more than that. Innovation is the human side of this. And how do we better reach people or how do we better understand how they're going to respond? It doesn't have to be just a technology solution. It doesn't have to be just a data solution. I think the social science side of this is incredibly important and we do need to do more work on that. We are kind of embedding and transforming our approach on this front end of preparedness and mitigation. It's about understanding individual communities better and their needs and their barriers, right? If we can understand their barriers, then we can put the programs in place to overcome those barriers.

Andy Revkin - I wanted to ask you one last question, which is what does success look like, let's say four years from now? What's something that can be done that would give you a sense we're on the right path as we navigate this multilayered risk landscape?

Deanne Criswell - I think that's a good lead-in to how I would think about this. To me, successes is we have a better way of identifying what the potential future risk is going to be and that we're working to reduce the impacts of that. And so the next generation of emergency managers is better prepared to support and protect their communities. I've often said that this is the crisis of our generation, but success to me is that we are taking the appropriate steps now so that the next generation of emergency managers is more prepared to support their communities.

Andy Revkin - Is there a way to envision a day when, along with thanking first responders, which we all do after an event, we [begin] thanking first preventers?

Deanne Criswell - I love that.

Andy Revkin - Is that a job title?

Lori Moore Merrell - It should be.

Resources and reading

U.N. Pushes to Cut Worldwide Vulnerability to Climate Extremes Through Better Early Warnings - My Sustain What post on a commitment to better bridge data and decisions

Read last fall's Sustain What post on ways to Shake out Community Climate Vulnerabilities, which also featured Deanne Criswell of FEMA along with "disasterologist" Samantha L. Montano and Jeffrey Schlegelmilch, the director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness here at the Columbia Climate School. Here's the related webcast:

Click here for a highlight from that brainstorm - Montano's call for a community-led movement for what she calls disaster justice as a vital way to prod government at all levels to shift the balance from response to preparedness.

Support Sustain What

Any new column needs the help of existing readers. Tell friends what I'm up to by sending an email here or forwarding this introductory post.

Thanks for commenting below or on Facebook.

Subscribe here free of charge if you haven't already.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues!

Ilan Kelman, an expert on disaster preparedness and response at University College London, sent this FEMA thought by email:

Regarding FEMA, (i) avoiding and responding to disasters should always start locally, scaling up only when needed, and (ii) FEMA has long had many problems, irrespective of amazing, dedicated, competent personnel directly helping those in need. Certainly, there is no expectation that those in the White House know what they are doing, or even care, regarding disasters and FEMA. A thorough, careful review of FEMA (and USAID) is long overdue, provided that the outcomes are (i) improvements and (ii) not hurting people during the reviews and the changes. It is doubtful that either outcome is desired or will be achieved by those conducting the reviews. Here's his book: Disaster by Choice: https://www.amazon.com/Disaster-Choice-actions-natural-catastrophes/dp/0198841345