Hansen: On a human-heated planet, it's time to add another red side to the CO2-loaded climate dice

Revisiting a 2008 interview with the pioneering and edge-pushing NASA climate scientist Jim Hansen

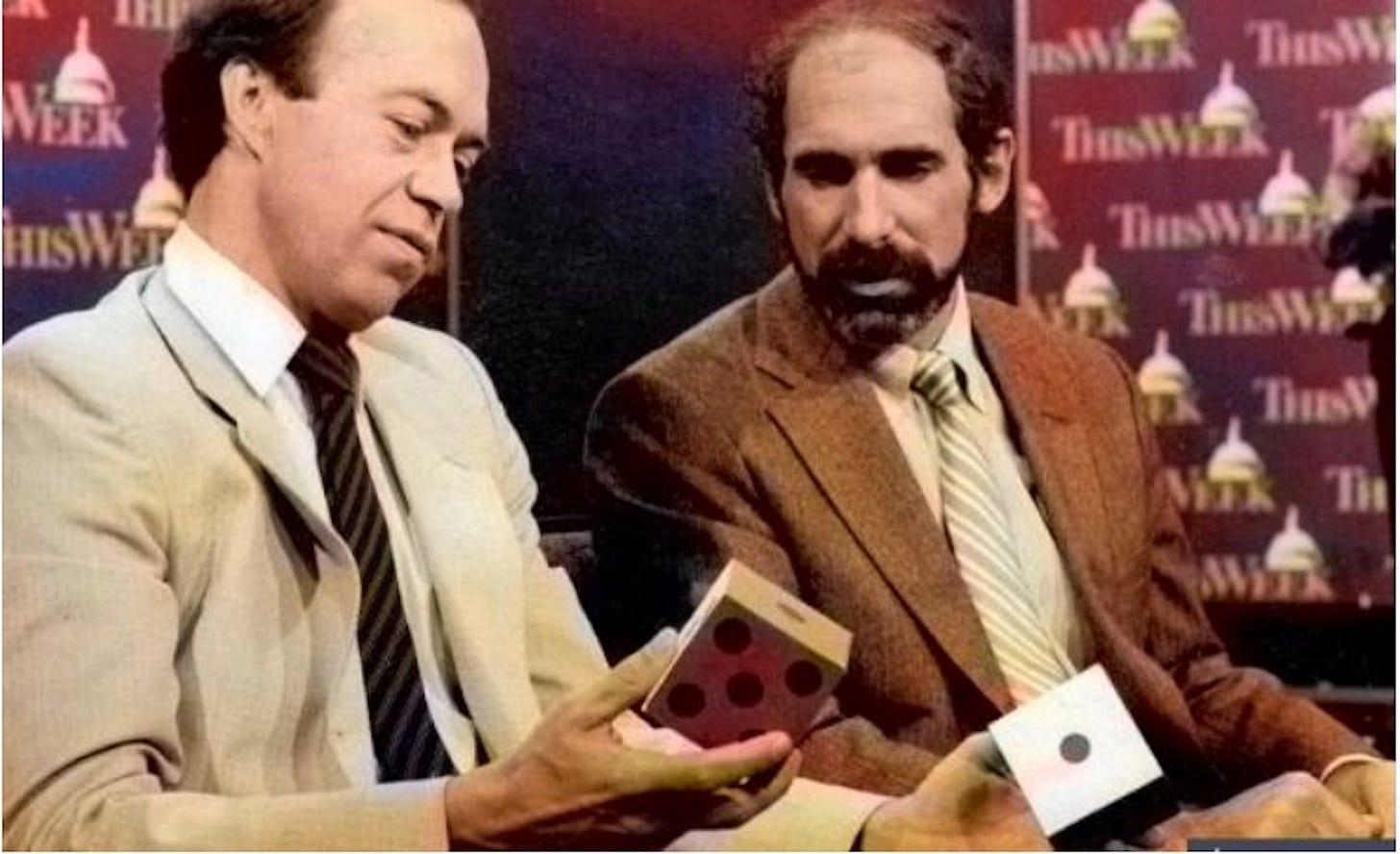

In the hot summer of 1988, several times after NASA scientist Jim Hansen delivered landmark Senate testimony asserting human-caused global warming was under way, the pioneering researcher wielded a home-made set of “loaded” cardboard dice to explain the shift in odds of hot days to lawmakers and the press.

Twenty years later, in the summer ahead of the election that put Barack Obama in the White House, I visited Hansen at his Goddard Institute for Space Studies office and used my camcorder to record an interview about the his climate journey and the climate dice.

Among other questions, I asked, “When would you have to paint a new face red?

Hansen replied, “I would guess, without looking at calculations, that it’s only of the order of another 10 or 15 years. It might be 20 years.”

I recently realized that 15 years had passed and sent him an email asking that question again. And, as long been the case, it turns out his calculations were spot on.

He just posted a newsletter answering my question. And the dice (no surprise really) do need an update!

Indeed, Hansen says, “It seems that we are headed into a new frontier of global climate.”

Here’s an excerpt, followed by other resources for you to explore. Note what he says about the odds of extremely hot summers:

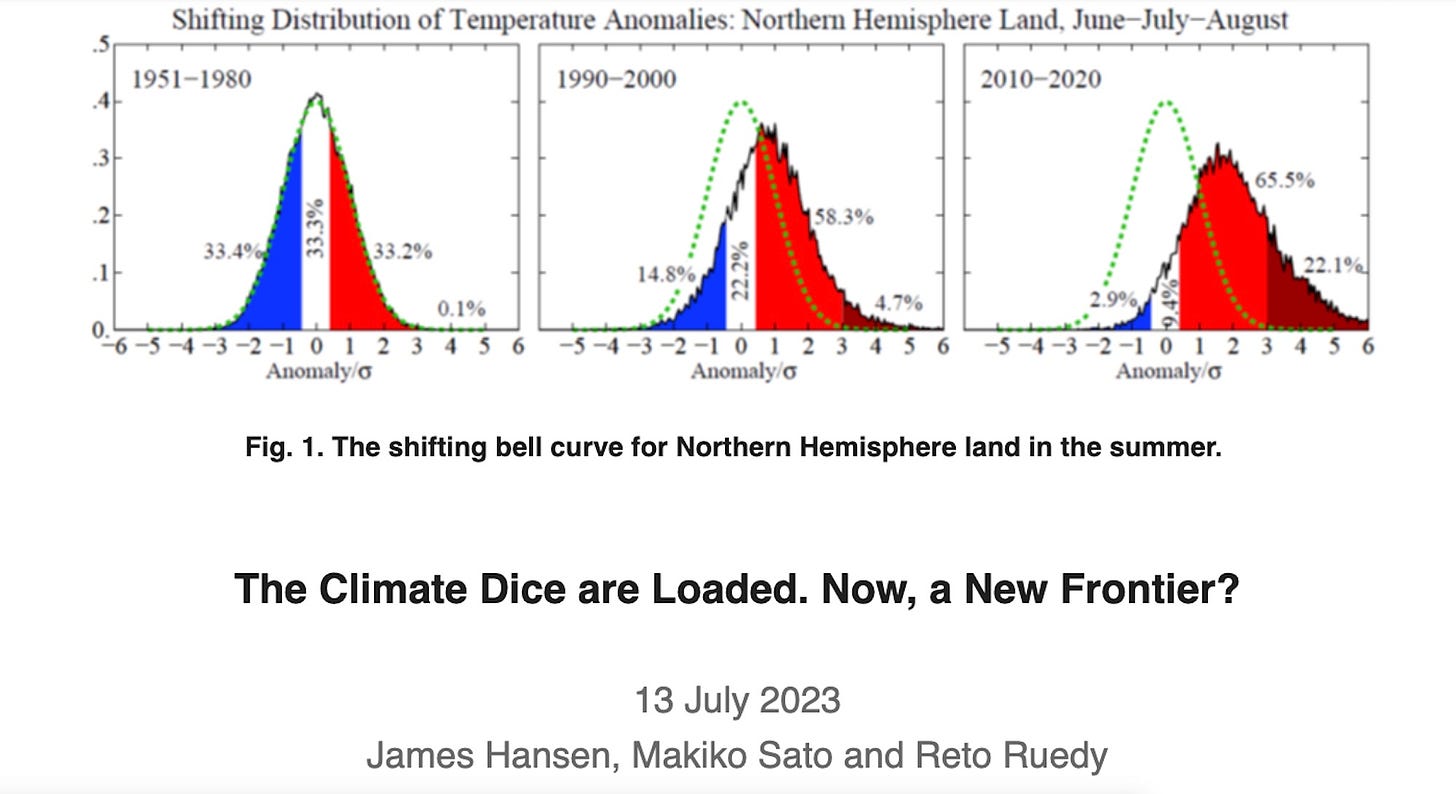

Andy Revkin recently asked whether the “climate dice” have become more “loaded” in the last 15 years. Climate dice were defined in 1988, after we realized that the next cool summer may cause the public to discount human-caused climate change. The answer is “yes,” the dice are more loaded as we will explain via the shifting bell curve (Fig. 1)….

A 1-page description of the bell curves and climate dice is available as the author summary of our PNAS paper on the topic. The variability of summer mean temperature in the base period (1951- 1980, prior to the period of rapid global warming), is described by the bell curve on the left.

By definition, the one-third of summers closest to average temperature are the white, warmer summers are red and colder are blue, thus each color covering 2 of the 6 sides of the dice.

By the last decade of the 20th century, red conditions were occurring 63% of the time on Northern Hemisphere land, which is almost the 67% needed to cover 4 sides.

Twenty years later, the red area is 87.6%, five sides of the dice. So, the answer to Andy’s question is: yes, one more side is red. The more important point is the dark red area on the bell curve, the portion that exceeds three standard deviations. These are extremely hot summers that seldom occurred in the base period (less than 1% of the time). Chance of occurrence now is more than 20%, thus covering more than one side of the dice (one side is 16.7%). Increase of such climate extremes has the greatest practical importance.

Read Jim Hansen’s full newsletter here and do subscribe!

Rising Odds of Extreme Heat

Anyone living in the southern tier of the United States now locked in a heat dome, or in similar conditions in parts of Europe and Asia, will recognize that importance. Do Read Jeff Goodell’s new book The Heat Will Kill You First, for more, and listen to Kristie Ebi, one of the world’s leading scientsts working at the intersection of climate and health, to learn why “nobody needs to die in a heat wave.”

Here’s the 2008 New York Times story I wrote centered on that interview: NASA’s Hansen: Humans Still Loading Climate Dice - and here’s the video (excuse the shakiness; back then it was really just for notes!):

Read the relevant in-process draft chapter from Hansen’s forthcoming autobiography for fascinating details about his approach to conveying the greenhouse challenge.

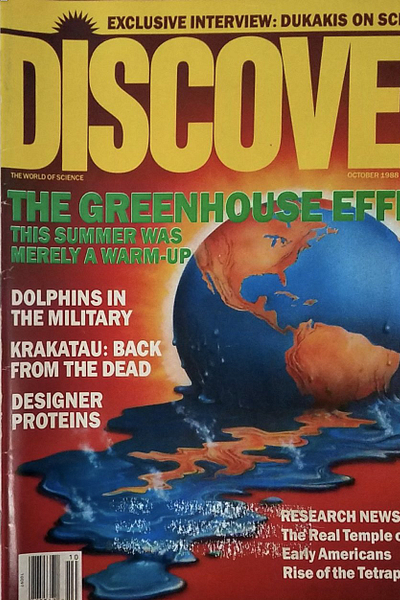

The warming view from 1988

Read my 1988 Discover Magazine cover story on that momentous year when global warming first made headlines:

Here’s a rough transcript of the 2008 conversation as kind of a historical artifact, or for those who don’t have time for the video:

Jim Hansen on Loaded Dice and Climate Change - June 2008 interview

Andy Revkin - So explain the dice. This was a you came up with this as kind of a speaking point. Was it the first time in 1988 for that hearing or before?

Jim Hansen - Yeah, well, it was right after the 1988 hearing because of the misinterpretation that some people made. You know, when you talk about global warming, then when you have a cool day or a cool month or a cool year, people think, oh, that must be a lot of baloney. But in fact, the problem is that global warming is relatively small compared to weather fluctuations. So all you can do is look for a change in the frequency of warmer than normal times. And if you average over a season, then it's a little easier to see anomalous temperature change. So what I did was make one die, which was supposed to represent normal conditions, which was the 1951-to-1980 climatology. And for that period, the National Weather Service had defined warm seasons, unusually warm seasons as those which occurred 30 or 33% of the time. And unusually cold conditions are those 10 out of the 30 years that were the coldest. So I had two sides of the die read for hot, two sides, blue for cold and two sides of white for average. And my point was that by the end of the century [2000] - in our intermediate [emissions] scenario [Scenario B] - the frequency of warmer than normal seasons would increase to about 60 to 70%. So that made four sides of the die red and one white for normal and one blue for colder than normal. So even after this warming, you can still get seasons that are colder than they were in the period from 1951 to 1980. And by the way, this has turned out to be about right. It's now [in 2008] a little more than 60% of the seasons are in the category that was warmer than normal in 1951.

Andy Revkin - Now, when would you have to paint a new face red?

Jim Hansen - I would guess, without looking at calculations, that it's only of the order of another 10 or 15 years. It might be 20 years.

Andy Revkin - Do you think people have largely misunderstood that this is kind of an odds-changing enterprise, not fixing something? I mean, we're not fixing the climate system per se, right?

Jim Hansen - Well, I think that's not a hard concept for people to understand. You know, we we'll have a very unusually mild winter, for example. And I notice relatives that I have in Minnesota, people say, boy, these guys were right about global warming when we had a really warm winter with almost no cold weather a couple of years ago. But then a year later, the winter was quite cold. And so people do mis tend to misinterpret the unusual weather events, even though the chances of having that and the extremity might be related to global warming. But it doesn't mean that the warming is large enough to dominate over natural variability.

Andy Revkin - What about industry and inertia.

Jim Hansen - Well, I think the reason that we didn't really work on solving the long term energy problem up until well, we still haven't really begun to do it is because of the role of special interests. The fossil fuel industry is doing fine and they will continue to do fine even if there's a limited supply, in fact, that causes the prices to go up and they make more money, why should they? So if you look at the people in Congress who are arguing against climate actions and against taking the steps that we would need in order for renewable energies to take over, which is where we have to go in the long run, you'll see that many of those congresspeople are to receive funding or campaign contributions from the fossil fuel industry.

Andy Revkin - So here it is, 20 years after June 23rd, 1988, and your language has gotten stronger, The data have accumulated and the climate bill has foundered. And presidential candidates are kind of touching on energy. But it's all about gasoline right now. I mean, are you if you could choose a metaphor, are you Sisyphus or are you Job? What are you feeling like these days? [Gas prices had spiked.]

Jim Hansen - Well, that depends on what happens in the next year. There's a strong similarity, actually an uncanny similarity, between the situation 20 years ago and the situation now in the sense that there is a big gap between what is understood about global warming by the relevant scientific community and what is known by the public and policymakers. And in both cases, we can see what's happening in the climate system with much more confidence than the public realizes. But the big difference is that we've run out of time to deal with the problem. We really have to do something for practical reasons. It needs to be next year because that's when we get a new administration, when we have to make the plans for what happens beyond Kyoto [the Kyoto Protocol climate agreement] and when we have to get the U.S. involved. So it's really a very short time fuse.

Andy Revkin - What's your elevator pitch for the next president?

Jim Hansen - I mean, first of all, you've got to make the scientific case that we are at a very dangerous point if we don't begin to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the next several years. And really on a very different course, then we are in trouble. The ice sheets are in trouble. Many species on the planet are in trouble. But the other the thing that I would really emphasize is that the problem is solvable. We can make the inevitable transition to renewable energies, but it requires a major initiative, and specifically it requires a national low-loss electric grid, a DC grid, a high-voltage DC grid, one which you should bury so that it doesn't so that people don't object to the impact on the views, on the environment. And we can do that. The technology is actually available to do that. And we could do it in less than a decade. We could get the backbone of a national grid in place. And that would allow renewable energies, which are many of which are intermittent, but which with a low-loss grid, that's not a problem.

It’s worth noting that, in later years, Hansen became convinced that renewable energy couldn’t supply humanity’s energy needs and that nuclear power was essential.

Andy Revkin - And how would you make the case? A grid is kind of a wonky, invisible thing. How do you make that case?

Jim Hansen - Well, it's pretty simple. I mean, it's like saying the National Highway System in the 1950s, we decided on that and we and we did it and we could do this or it's like the the Moon program, which Kennedy described. It's a simple concept. And a new president could take that as one of his major actions. And he should do it next year because we're running out of time. Because of the long life of CO2 in the atmosphere and the fact that we've got these sources which we're not going to shut down suddenly, we're certainly going to have additional CO2 in the atmosphere. What if we would phase out coal except where we capture the CO2 by 2030? Then, because of the finite volume of oil and gas, we could get back to 350 [parts per milllon] within a hundred years, provided we didn't exploit unconventional fossil fuels.

Andy Revkin - And what about the China question? What do we do? What can we do to see that.

“Climate change is not today's emissions; it's today's atmospheric composition.” - Jim Hansen

Jim Hansen - China is inappropriately made a scapegoat in this case because what causes the climate change is not today's emissions; it's today's atmospheric composition. And we are primarily responsible for the excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, more than three times more than China. And actually on a per-capita basis, more than an order of magnitude more responsible. So to blame China and say we have to wait for them is nonsense. Oh, well, yeah. In the short term, we have to have a moratorium on new coal fired power plants, and that should start in the United Kingdom, the United States and Germany, in my opinion, because those three countries are the most responsible for the excess CO2 in the atmosphere on a per capita basis. And actually, it's in that order the United Kingdom, the United States and Germany, because the UK started an Industrial Revolution soonest and some of that CO2 is still in the atmosphere. So, you know, so that's why I wrote a letter to the Prime Minister and to the Chancellor of Germany trying to convince them if one of us, one of the three countries would take the first step, then probably we could convince the other two and then eventually the European Union and get the ball rolling. But we really need to stop building coal fired power plants. They tend to sit there for 50 years and produce CO2 for 50 or 70 years and up every day one of these big plants will burn 100 railcars. Of course, it's an incredible amount. So is citizens taking small steps to reduce their emissions will really be fruitless if we continue to build anything apart.

Andy Revkin - Do you do you have do you ever wake up having regrets about stepping so far into the realm of policy and and messaging as opposed to just hunkering down doing your science?

Jim Hansen - I only regret that we haven't got the story across as well as it needs to be. And I think, you know, I think we're running out of time.