Food Worries Widen as Russia's Ukraine Invasion Turns a Global Breadbasket into a Battleground

Putin's war on Ukraine is also a war on food security in far-flung hunger hot spots, from Uganda to Yemen

Please SUBSCRIBE to receive my posts by email (content always free so those who need it most can get it). Spread word to friends by sending an email here. Support Ukraine and Ukrainians in a host of ways ine and Ukrainians in a host of ways here.

Sunflowers in Ukraine; the country is a top exporter of sunflower oil (Wolodymyr Lavrynenko, CC BY 3.0)

UPDATED 2pm EDT 3/18:

With millions of citizens forced from their homes and Russian forces advancing on or attacking municipalities large and small, Ukraine is in crisis. Now the impacts are widening.

Vital flows of crucial commodities to some of the world's most hunger-prone hot spots are already being disrupted at several stages of the farm-to-table journey by Vladimir Putin's intensifying invasion. Ukraine has stopped exports given threats to ports. Farmers have to choose between fertilizing fields right now - a critical need for good yields - and defending their country. Russia just announced export curbs, according to Gro Intelligence. Rising energy prices are jolting fertilizer costs.

And this is happening as the highest prices for some staples in more than a decade have already been worsening hunger.

Agriculture experts say much greater, and more enduring, food impacts loom if Vladimir Putin doesn't stop this violent assault on a neighboring country and global norms.

At the United Nations on Monday, Secretary-General António Guterres put it simply: "This war goes far beyond Ukraine. It is also an assault on the world's most vulnerable people and countries."

Notably, regional warfare and conflict, even more than climate change, had recently been pinpointed as the main driver of resurgent hunger in significant parts of the African continent. Now warfare to the north is piling on.

On Friday I organized a Sustain What webcast to learn what's already happening with Ukraine's farms, ports and markets and what is likely to unfold ahead. I was joined by an array of seasoned journalists and experts focused on the nexus of conflict, farming and food. My goal was to highlight solid steps that can cut odds of shortages and price spikes tipping into unrest or even famine.

Watch here on YouTube here or Facebook or LinkedIn:

Here's an advance look at some of what we'll explore. Please point me to other sources of expertise or data and do join us on Friday.

Farmers in Ukraine - Jim Richardson website

A battered breadbasket

Ukraine has for generations been a regional and international breadbasket and its position as one of the world's top global exporters of wheat, corn, sunflower oil and other commodity crops had been rising in recent years.

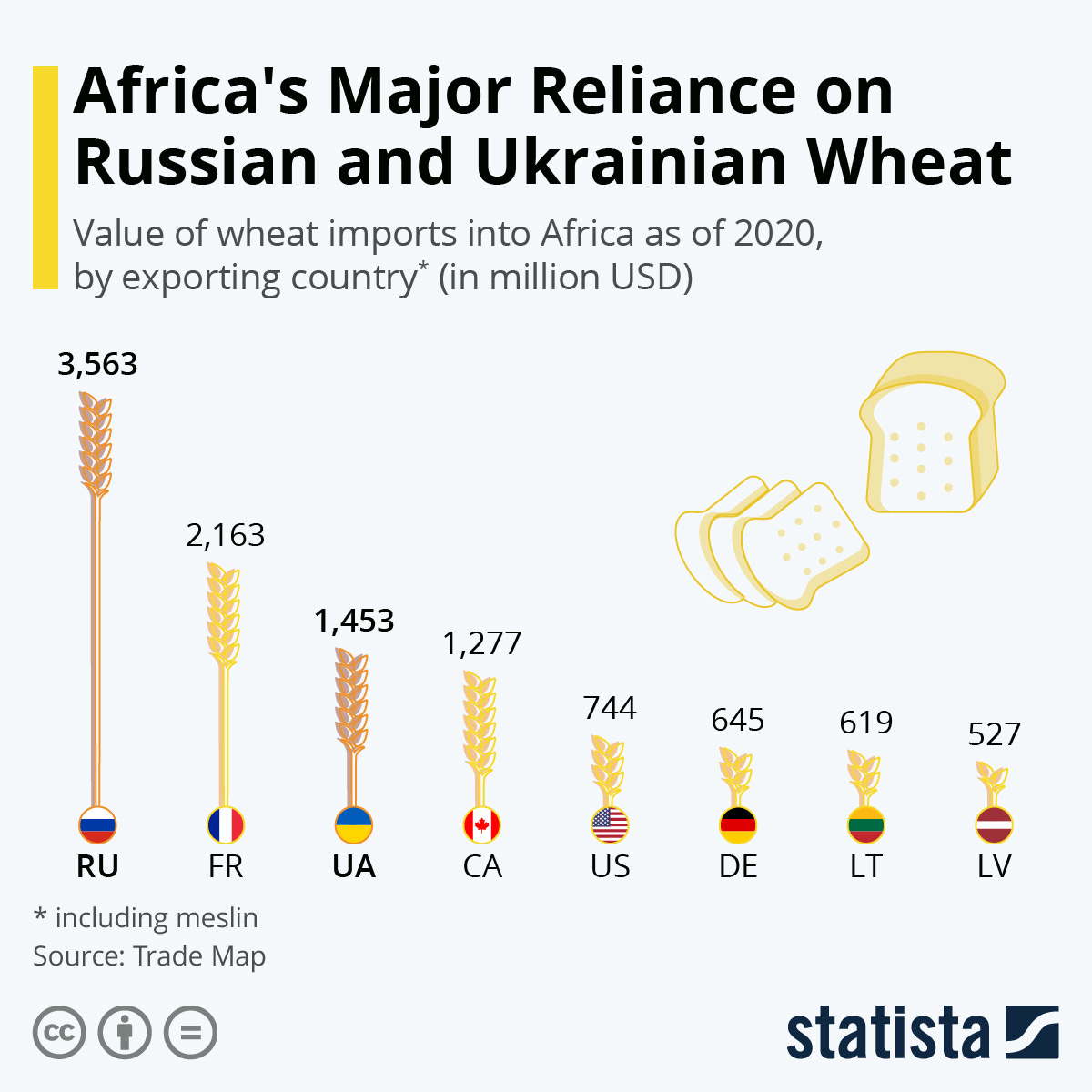

More important in the context of hunger, Ukraine's wheat, shunted through its Black Sea ports, has been particularly significant in the Middle East and northern Africa.

Here's one visual snapshot of its ranking in Africa, via Statista:

But the outsize role of Ukrainian grain exports extends across a wide arc of countries facing nutrition gaps through a mix of conflict, pests, climate extremes and lack of development or governance. As Alex Smith of the Breakthrough Institute warned in Foreign Policy back in January, "Of the 14 countries that rely on Ukrainian imports for more than 10 percent of their wheat consumption, a significant number already face food insecurity from ongoing political instability or outright violence. For example, Yemen and Libya import 22 percent and 43 percent, respectively, of their total wheat consumption from Ukraine."

Two researchers at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Hendrik Mahlkow and Tobias Heidland, just ran a model projecting food supply drops and price spikes across a range of countries and the picture is a sobering one:

Click for the paper and larger versions of these graphs

Tobias Heidland was among those joining my webcast.

Also on board was Maryn McKenna, a longtime science and health writer who just filed a Wired story that lays out how the war, by disrupting each step along the food chain, is poised to create big problems:

"Goods that have already been harvested—last autumn’s corn, for instance—can’t be transported out of the country; ports and shipping routes are closed down, and international trading companies have ceased operations for safety. (Plus, while those crops sit in bins, destruction of the country’s power grid takes out the temperature controls and ventilation that keep them from spoiling.) This year’s wheat, which will be ready in July, can’t be harvested if there’s no fuel for combines and no labor to run them. Farmers are struggling over whether to plant for next season—if they can even obtain seeds and fertilizer, for which supplies look uncertain. (Russia is the world’s biggest exporter of fertilizers; it suspended shipments last week.)"

Limited global effect

One of the foundational values of global food trade is plasticity and resilience and this means chances of global shortages of key commodities are slim to none, as was compellingly argued by Aaron Smith, an agricultural economist at the University of California, Davis in a March 9 post.

He urged the United States not to rush out incentives for farmers to boost production. But he did echo Secretary-General Guterres's point about risk where vulnerability is already heightened by poverty and food constraints.

"The transition may be difficult in some places, especially countries such as Egypt that typically rely on wheat from Russia and Ukraine," Smith wrote. "Helping such countries find alternate suppliers would be better policy."

Via Twitter, I asked Smith for more on what that help should look like, and he pointed me to a Twitter thread by Joe Glauber, a former chief economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture who's now a senior research fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute.

Here's the core point from Glauber, with some Twitter shorthand cleaned up:

"The potential loss of the Ukraine wheat crop to the world is significant…. Egypt and other wheat-consuming countries…will pay a LOT more for wheat. There may be some substitution (like barley) at the margin but I think many countries will just pony up with large (hopefully targeted) consumer subsidies. That costs money. For poorer countries like Yemen, who import almost 100 percent of their wheat, they will need a lot of assistance if they are to meet food needs. And in the past, the World Food Programme and others have sourced a lot of grain out of the Black Sea.

"…Over the long run, high prices encourage farmers to sow more wheat and prices will moderate. But the longer the war disrupts Ukraine production, the longer that adjustment will take, which places large fiscal burdens on governments’ intent on keeping food prices low and for international organizations providing humanitarian relief.”

(Also read the February 24 report on Russia's Ukraine invasion and food security by Glauber and his colleague David Laborde.)

The view from Ukraine

In a webcast I sat in on last week, Oleg Nivievskyi, an agriculture-focused researcher at the Kyiv School of Economics, described a pretty dire scenario after adding up the disruptions to farming and trade. Under a worst case, he said:

"It looks like that there's going to be no exports from this from this region for a couple of years to come. And this is really serious because in that case, the world will be missing overall, about 60 million tons of grains.

"If we take together Russia and Ukraine, that's close to 30 percent of the global trade - not global production, but global trade, which is quite a substantial amount of grain. For the Western countries, that's going to be painful, but it's bearable. Europe and other countries can cope with that. But what's really going to be a problem is the Middle East and northern Africa. And, you know, some observers are telling us there’s going hunger, riots. We're going to have real problems over there because there are going to be the threats of hunger and malnutrition and increased poverty.

"This is really what's going to happen, at least if this madness that's happening right now in Ukraine does not stop soon."

Here's my previous post on other urgent issues explored in that Tufts University webcast with a batch of Ukrainian scholars. Here's the full video. Here's Nivievskyi making the point above:

Nivievskyi joined the discussion, as did Dennis Dimick, a journalist who has focused much of his career on stories about agriculture, including during long stints in several top editorial roles at National Geographic.

Another guest was Anna Bulakh, a professor at Kyiv School of Economics with deep expertise in international security, online technology and defense.

Parting shot

Here's a bigger look at that banner image showing Ukraine's agricultural splendor in better times - times that hopefully will return as this spasm of imposed violence ultimately fades:

Tractor on a field, Kasova Hora, Ukraine, April, 2018 (Vian, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Help build Sustain What

Any new column needs the help of existing readers. Tell friends what I'm up to by sending an email here or forwarding this introductory post.

Thanks for commenting below or on Facebook.

Subscribe here free of charge if you haven't already.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues.