Feeding 8 Billion + on a Heating, Human-Shaped Planet

Come on a visul tour of the world's spectacular, and straining, food systems

If you appreciate what I’m doing here, clicking the ♡ button supposedly boosts the post’s visibility on Substack. And of course subscribe and, if you can afford it, financially support Sustain What.

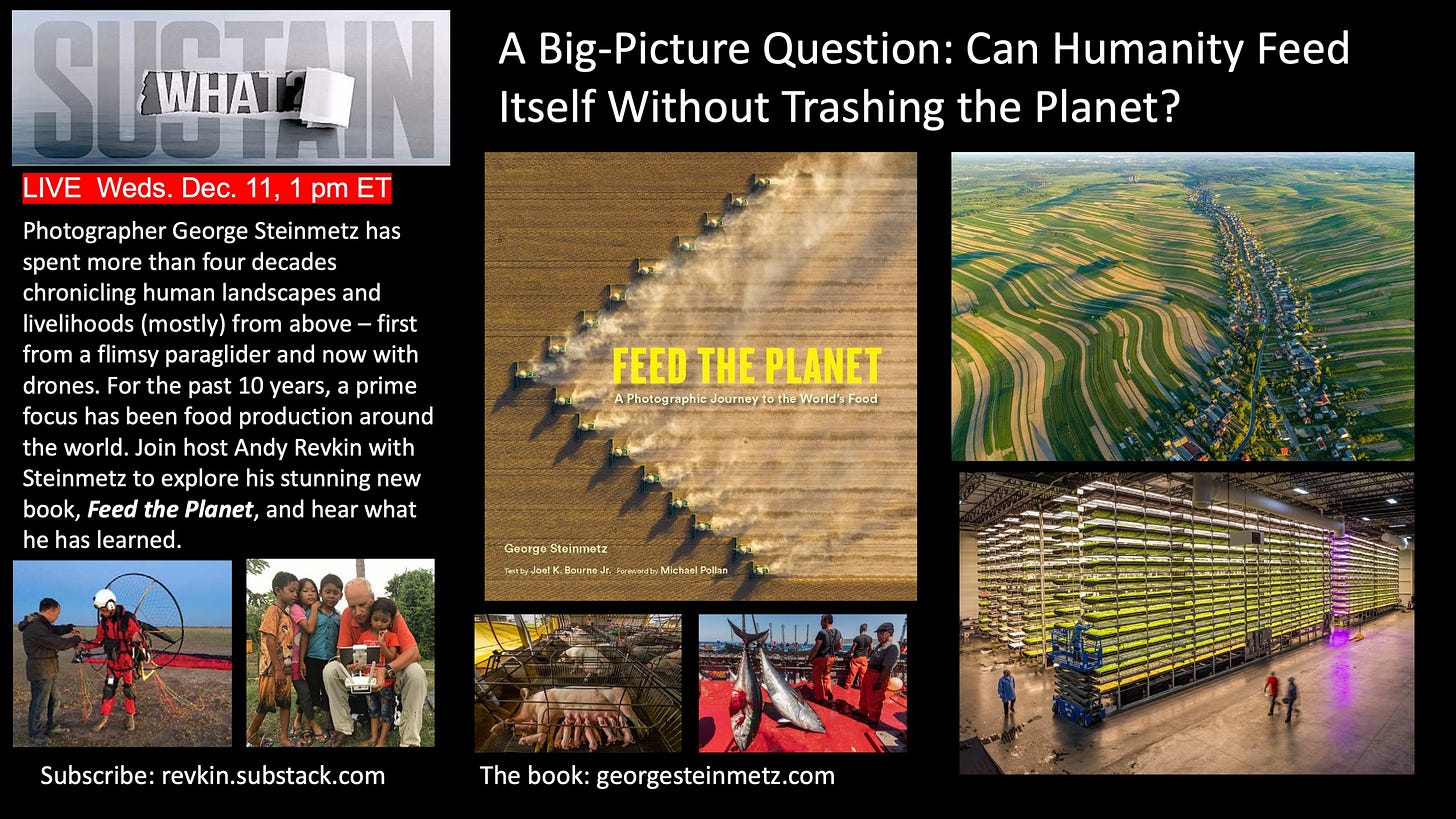

Updated post-broadcast: Please watch my food-focused Sustain What conversation with my friend George Steinmetz, who has spent the same four decades I’ve been reporting on global change photographing it - mostly from above, and in his pre-drone decades from the dodgy vantage point of a powered paraglider.

He is truly one of a kind. This image from his last book, The Human Planet, for which I wrote the text, says heaps about his obsession with aerial vantage points:

A top-down view of fish, fields, flocks and more

Steinmetz has a singular obsession with capturing and conveying the dynamics, for better or worse, at the interface between communities, resources and ecosystems. For the past decade he has centered most of his photography on a single theme: how human communities around the world glean or raise food - from deserts to the deep sea, the arctic to the tropics, fields to laboratories.

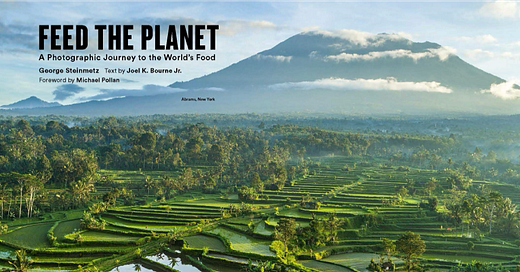

He has distilled the best imagery into a new book that is a visual feast, Feed the Planet, with text by the journalist and author Joel K. Bourne, Jr. and a foreword by Michael Pollan.

You can get the feel for the book in Steinmetz’s million-follower instagram account:

Watch and share here or on LinkedIn, my X account @revkin or YouTube. And please share this post with others who’d be interested!

In the second half hour, we were joined by two researchers focused on food and nutrition economics and trends, William A. Masters of Tufts University and Amelia B. Finaret of Allegheny College, who are the authors of the open-access textbook Food Economics.

On Bluesky, I noticed that Masters took issue with a Science Magazine article distilling some of the book’s focus on large agriculture systems. Here’s one graph he posted from the textbook showing how the vast majority of farms around the world are miniscule operations.

Also watch my 2021 Sustain What conversation with Steinmetz, done around the release of our book The Human Planet - Earth at the Dawn of the Anthropocene:

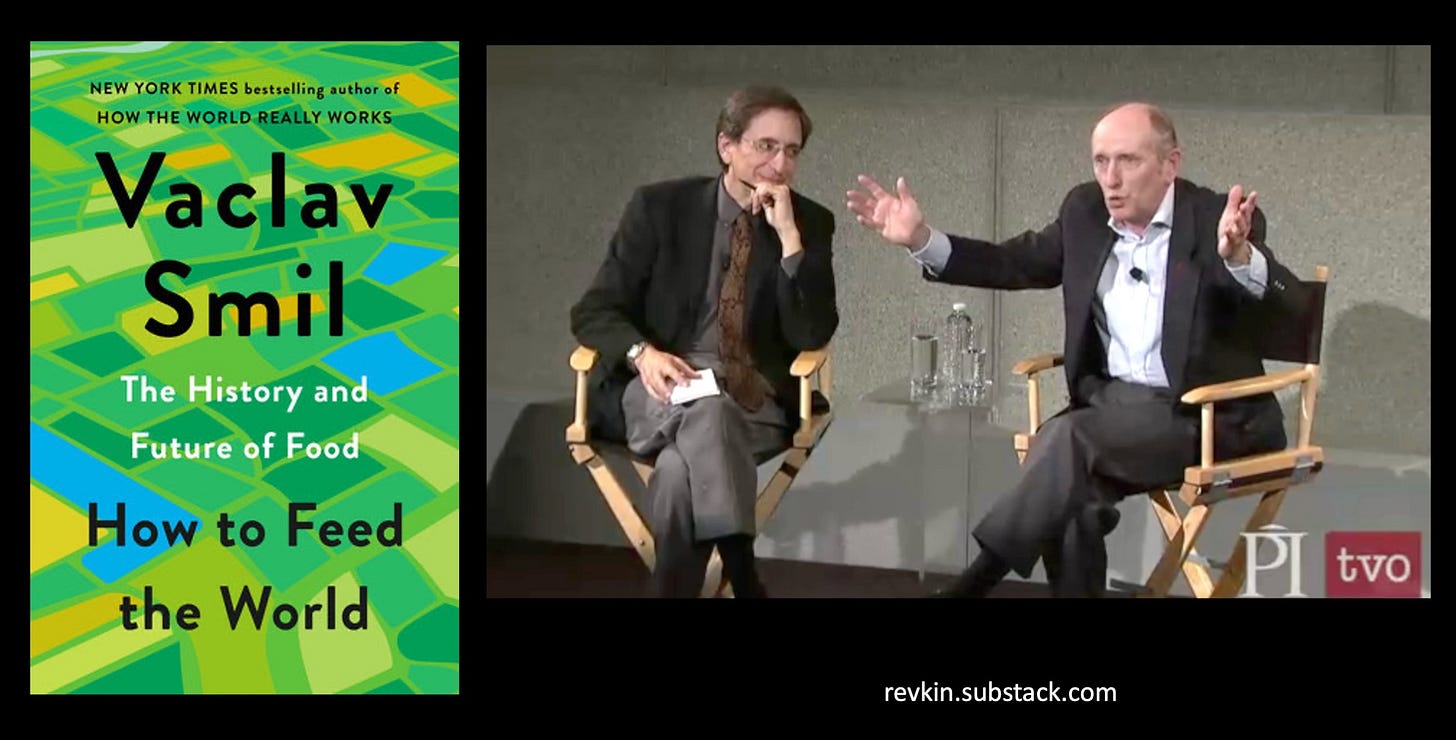

Vaclav Smil’s recipe for feeding the world

Someone else who’s tracked food and agricultural trends for decades is one of my top go-to brains on resource trends, Vaclav Smil. If you’ve never seen the 2009 conversation we had at Canada’s Perimeter Institute on this question - 9 Billion People + One Planet = ? - I urge you to do so.

Smil’s new book, How to Feed the World, is being published this spring and I’m posting a foundational conclusion below [with my bracketed notes] and will be citing it in this conversation:

[A] realistic outlook for maintaining adequate global food supply remains promising. No unprecedented gains and no untried radical solutions are required to provide the next generation with adequate food supply: we just need to keep on improving production efficiencies, reducing waste, adjusting diets, and promoting measures that reduce food’s overall environmental impact. [Keep in mind that word “just” hides a lot of big challenges]

Declining populations (now the norm in all high-income countries that do not allow large-scale immigration), falling fertility rates (which includes all populous countries, with Asian rates already below or near the replacement level, but with African countries still well above it), and moderating demand for food (typical of all aging societies) should make these quests easier than we thought a generation ago, when the best long-range forecasts saw the global population rising well above 10 billion people. Now the most likely outlook is for a peak of 9.7 billion by the mid-2060s, followed by a decline to about 8.8 billion in 2100, a total some 2 billion lower than some previous forecasts. [After three decades tracking population trends, I’m with him on this, despite assertions by overpopulation campaigners and Musk-style implosion catastrophists.]

At the same time, the unequally distributed climatic consequences of global warming will bring a combination of negative and positive changes, and hence the quest will become harder in some regions and for some crops. And while the potential for radical gains due to the genetic modification of crops and animals looks impressive, the dates of large-scale commercial adoption remain unknown, as do the prospects for any substantial voluntary modifications of prevailing diets. Global transitions take a long time. [See my recent reality check on the slowness of energy transitions.]

There is nothing new in facing such combinations of uncertainties. I wrote this book to offer facts rather than speculations, and as it happens, the facts are reassuring. We should remain suspicious of any long-range quantitative forecasts, but—considering basic biophysical realities, continuing performance gains, and a realistic assessment of future improvements—it is rational to argue that, barring mass-scale conflicts and unprecedented social breakdown, the world will be able to feed its growing population beyond the middle of the 21st century, when the combination of new demographic realities and new scientific advances may present us with entirely new options.

So please watch and share this conversation and weigh in with food practices and experiences that you see leading in a positive direction.