Exxon Beware - Students and a Senator Vow to Demolish Climate Inertia

Spread care, call out the culpable, price pollution

Slowing global warming and cutting climate risks are simple in principle: Stop adding heat-trapping pollution to the atmosphere. Stop building in harm's way and shunting the poor and marginalized into danger zones.

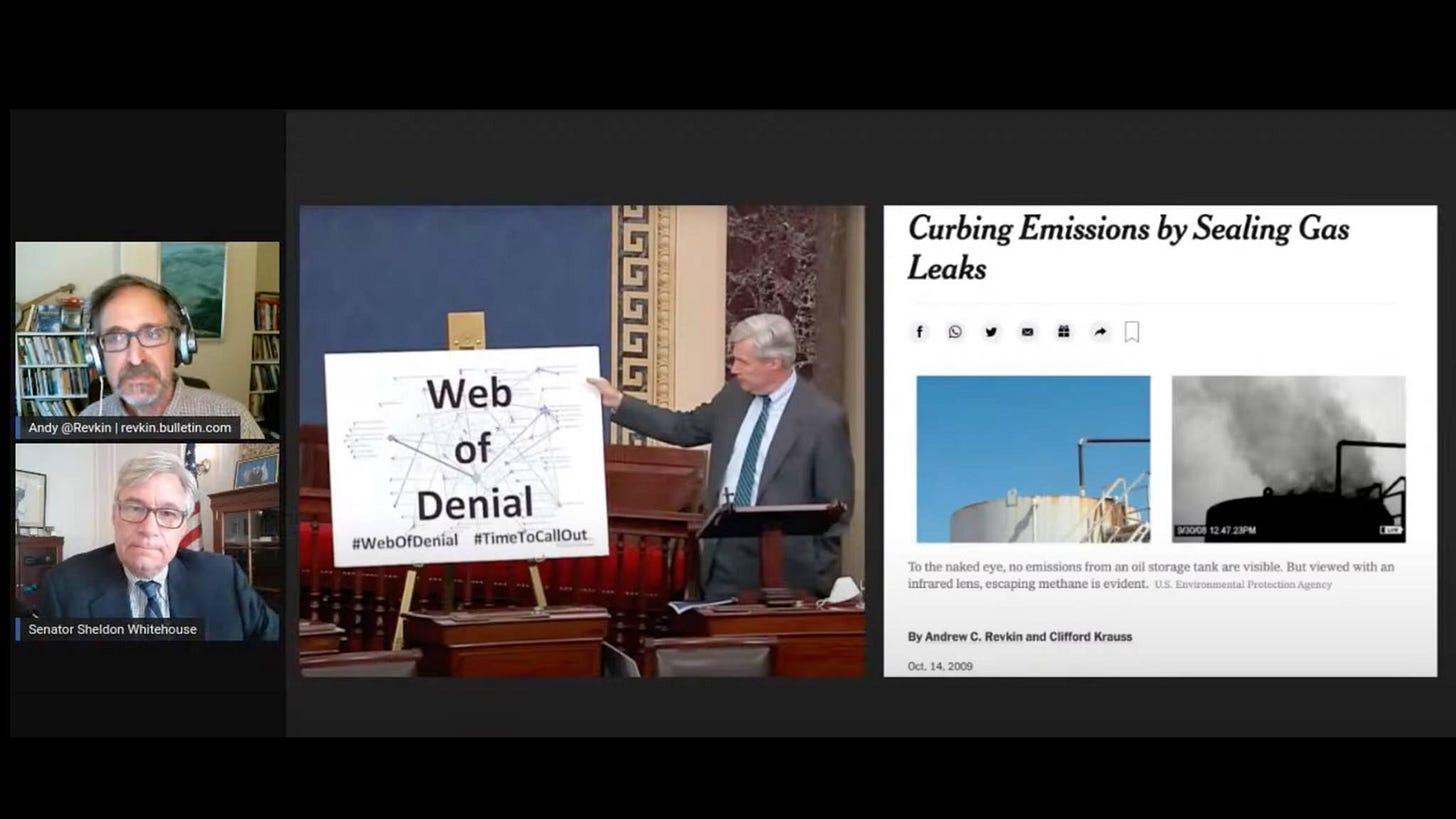

Countless forces have blocked progress on both fronts. This week, I hosted a Sustain What brainstorming session on overcoming climate inertia with a senator famed for his dogged climate activism and two Columbia University students passionate about building a more just and climate-resilient society.

They identified fresh ways to gain traction, all involving social action that builds from the community up. But Exxon Mobil and its allies shouldn't think they're off the hook. Read why.

The students are Sofia Assab, a senior majoring in sustainable development and Gabrielle JoAnn Batzko, a graduate of Appalachian State University's Sustainable Technology program who's entering the Climate and Society master's degree program at Columbia this fall.

The senator, of course, is Sheldon Whitehouse, the Rhode Island Democrat who's been on a decade-long mission to expose the web of political money and public disinformation impeding congressional action on climate change (hashtag #webofdenial). In reports and nearly 300 "Time to Wake Up" floor speeches, his message has intensified in parallel with the mounting evidence of momentous impacts from rising greenhouse gases.

Here are some highlights (edited for clarity and length). You can watch and share the video below. We started with what Senator Whitehouse sees as the critical reason Congress ground to a halt - the vast flood of political money unleashed by a 2010 Supreme Court decision.

How "Citizens United" killed climate collaboration

As a fellow Rhode Island native, I noted how starkly different environmental politics is now compared to decades past, including when the state's Republican Senator, John H. Chafee, opened 1986 hearings on the depletion of the atmosphere's protective ozone layer and "the problem of the greenhouse effect and climate change."

Andy Revkin

You're in a very different atmosphere now, unfortunately, in the Senate. It must feel like you're facing two crises on a daily basis - the climate issue that you care about so much and the paralysis of politics as we knew it.

You gave a floor speech last week after the [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] report came out and you said, "We have to do this now and unfortunately we have to do this alone." That was the darkest line to me. Maybe lay out why we have to do this alone, meeting the Democratic Party?

Sheldon Whitehouse

When I got to the Senate in 2007, I got sworn in by Dick Cheney. Through all of '07, all of '08 and all of '09, climate stuff was really bipartisan. We had bipartisan hearings. We had bipartisan bills. These were not small-ball bills. This would really have made a big difference and changed the trajectory on climate change.

And then it all came to a shuddering halt in January of 2010, exactly at the time of the Citizens United decision, which let unlimited amounts of money into politics, and guess who had unlimited amounts of money and a huge motive to manipulate politics? That's the fossil fuel industry.

They basically shut down the Republican Party and said, anybody who crosses us, we will crush. Anybody who toes the line with us, we will reward with enormous gouts of anonymized money.

And the bipartisanship collapsed literally overnight.

So that's the problem with the GOP. The fossil fuel industry at the CEO level says that they care about climate change, that they support carbon pricing and this, that and the other. But once you get past the CEOs and down into the fighting decks and out to the front groups that they fund and out to the trade associations that they support and direct, then the message completely reverses itself.

And they're still at full-on climate denial, full-on climate obstruction. And then the third party here is the rest of corporate America, which has a much better game of talk going than the fossil fuel CEOs and has [done] pretty good internal work on their own corporate carbon emissions. But when it comes to Congress, where I work, they're completely useless. Corporate America has built the most impressive and powerful lobbying and electioneering machinery ever. It dominates American politics and it has not switched on that machinery to do anything about climate change. And so it's really all talk and no political action.

Andy Revkin

The reconciliation process seems to be offering the prospect of some demonstrable steps. Can you could you outline your hopes?

Sheldon Whitehouse

There's a lot that we can do. Our problem, as with everything in reconciliation, is that we're going to need all 50 Senate Democrats to agree. We've been trying to strengthen up the climate measures that are in the Biden proposal, and we've had some good initial success. The addition of the methane fee is a big deal. It instantly moves in as the number three emissions-reducing intervention in the whole portfolio of climate interventions. And they have agreed in principle to adopt a border adjustment.

[The border adjustment would be a fee charged on imports of some products or commodities from countries without strong climate policies and rules.]

But we don't have details on that yet and we're pressing them for what they're going to connect their border adjustment to. Is it to a carbon price? Is it to the EU standard? Is it something new? In which case we need to have a look at it, kick the tires and see if it's actually going to work.

And then, of course, the big powerful intervention is a price on carbon pollution. It shouldn't be free to pollute. You can spend immense amounts of money to mitigate pollution and to discourage pollution, but if you're still allowing people to pollute for free, that's an incredibly powerful incentive and really hard to undo.

Is the fossil industry irredeemable?

I cited some reporting I did a decade ago showing that BP in the early 2000s was finding ways to eliminate leaks of heat-trapping methane from its gas fields even as competitors found it easier to drill new wells than fix older ones.

Andrew Revkin

When I talked to the American Petroleum Institute or other industry groups, I said, why isn't this your best practice? [There was no answer.] Is there a way for there to be an industry that does start to move toward best practices and where it isn't always being dragged in that direction?

Sheldon Whitehouse

I've been incredibly discouraged by corporate engagement on climate and a whole bunch of other issues as well. The CEO might have some nice ideas and have some things they want to say at the cocktail parties, but then it has to get kind of washed through all of their lobbying and political crew. And then they've got to work with their industry brethren, some of whom may not be so enlightened. And you go to the lowest common denominator and then you end up with the trade association lobbyists. And by the time we engage with that industry, the message is pretty craven and totally self-interested and pretty disgraceful, So I've really lost confidence in the ability of a corporation to honestly deal in the political sphere without immense public pressure behind it to force that kind of behavior - shareholder pressure, investor pressure if it's banks and others who are financing them, and public consumer pressure.

Political culture has a lot to do with this as well. The industry [in 2009] was responding to the Obama administration and to the public initially by doing quite a lot that they had agreed to in terms of voluntary reporting of carbon emissions. And then once it's reported and they're on the record, then you can go and there'll be pressure to clean it up. As soon as Trump got elected, they walked away from all of their agreements. They refused to report what they were leaking. Methane leakage continued to just pour into the atmosphere.

And that's where the methane fee comes in because we're going to charge them $1,800 a tone for what they leak. And that'll put enormous pressure on them to clean up their act. In fact, according to the modelers, we don't actually raise a lot of money with the methane fee because it's big enough that'll give them the incentive to go and clean it up in the first place, which is what they should have been doing. So it's frustrating to work with these people when the only way they respond is when you whack them in the head economically or when the public is really outraged.

Andrew Revkin

But that still leads to some possibilities because the public can get engaged on these issues?

Sheldon Whitehouse

It should be socially unacceptable to belong to the United States Chamber of Commerce in this day and age, while they have been identified as one of the worst climate obstructors in America and have not cleaned up their act yet.

They're in this sort of staged internal debate among their members about what position they're going to move to. But in the meantime, nothing has changed. They're still our adversaries.

They're still up to no good and they purport to represent all of corporate America. So lots of corporate America, including companies that claim to have really good climate policies, are completely aiding and abetting this immensely powerful trade association - triple the lobbying power of the second most powerful trade association - engaged in electioneering and out in elections, [which] uses dark money to fund candidates all the time, litigates, goes into regulatory proceedings and all of it on behalf of the fossil fuel industry. And the rest of corporate America is acting as if they've got no accountability for that. They don't own any of that. It's just somebody else's problem.

An Exxon "Potemkin Village"

We shifted to the public outreach side of the fossil-industry strategy and I showed him one of Exxon's Twitter ads.

Andrew Revkin

[These ads] kind of give this happy sense of a transition underway. And there are some organizations like Clean Creatives who are trying to out this process and they're trying to get ad agencies to abandon working with fossil fuel companies, which might be a tough one.

Sheldon Whitehouse

This stuff is really part of a fraudulent scheme. And I can remember years ago when they started putting Lucite molecules and scientists onto their ads and showing that they were investing in all this new clean energy technology. And we were able to determine that they were spending more on the advertisements than they were on the research. This was a Potemkin village. They built a fake village just so they can take pictures of it, just so they can have the tzar go by and see, you know, happy peasants dancing in clothes and looking like everything's fine in the country. And in fact, it's a complete fake.

This is one of the papers underpinning Whitehouse's arguments:

Students on a climate mission

Then the next generation of climate frontier pushers took the floor. Sofia Assab, from Northhampton, Mass., is focused on developing an economics that sustains the full sweep of society. At Appalachian State, Gabbie Batzko worked on ways to make clean energy useful and appealing in rural North Carolina.

Sofia Assab

As a young person studying sustainable development, much of what I see is so many people deciding to turn a blind eye to what's going on. And for people my age, I don't blame them because it's really hard to have hope for Earth or to think, oh, should I invest in a property when I'm young? Maybe that land is going to be gone in 20 or 30 years. My overarching question is just how do we begin to talk about this in the way that you say is so important, to have this in the front of our minds without a mass loss of hope?

Sheldon Whitehouse

It's much easier to despair when you don't understand the causes and the whole thing seems to be just coming out of the ether. What makes it easier for me to deal with is studying and understanding that this was actually a thing that was done. And it was done by the fossil fuel industry. And it was a very complex operation, but not that complex when you consider other intelligence operations that have been run around the world.

So the idea of running a big covert operation through a variety of front groups, hiding the sources of the money, having your plants in place who are basically paid to lie and dissemble.

But because we're American and because we generally think of democracy as an honest way of doing business, we have not been as quick as we should have been to recognize the structure, the system, the purpose of this apparatus that the fossil fuel industry set up, even when scientists studied it and identified it and marked the participants. Even then, it just didn't fit our narrative particularly well.

And so we let it grow and we let it run and we let it to do its wicked work. Now I think we've got to have a whole new conversation about what role corporations should have in politics after they have failed us so badly on this incredibly important issue.

And we've got to have a hugely important conversation about transparency in politics, because the fuel of this was dark money, anonymous money, the ability for Exxon or Marathon or API, whoever it was, to hide that it was them behind some phony front group with a name like, you know, Northhampton for Peace and Prosperity.

Gabbie Batzko

When I think of climate change, I think of the intersectionality of societal issues and disaster. When you were in Congress talking about the IPCC report and you brought up the maps of Rhode Island, it kind of describes how the geography would change based on flooding.

The people that are going to be displaced, they're already marginalized groups. They're going through things like student loan debt, racial, socioeconomic and gender inequality, broken indigenous treaties and rising housing costs. So they're not just going to be experiencing climate change, but there are all these other mental, physical and financial boundaries that are already placed on of them.

How can we expect people to finance personal solutions and mitigation efforts when so many people are already struggling to pay rent or afford medical care?

What do we have to do to get government officials at all levels to begin to consider socializing climate solutions and climate aid to help create equal access to safety from the climate crisis?

Sheldon Whitehouse

I would say, Gabbie, that I think that's starting to happen. And here is an area where I'll give the Biden administration quite a lot of credit. I think they are really determined to have this problem solved on a pathway of environmental justice. And that correlates very well with the strong work that we've been doing through the American Rescue Plan, through parts at least of the bipartisan infrastructure bill and through what we're planning in reconciliation to readjust the economic balance in the country so that it's not the poorest who are the most taken advantage of with a tax code that's upside down so that billionaires pay lower tax rates than their chauffeurs and their gardeners and their maids

So I think the two have to go together. This is a test of American democracy. If we can't solve climate change and if we continue to lead basically a rigged economic system, then that sends a really terrible message to people and they will get very angry and they will vote for more people like Donald Trump.

And you're right to see those intersectionalities because what people fundamentally want is to be heard. And to be treated fairly and to know that they've got a respected position in their society. And if you take those things away, there's really no way to patch it back up.

Gabbie Batzko

At Appalachian State, I focused a lot on sustainable technology, but also the theory and application behind communication, how to go about addressing these things so that everyone kind of feels included. We were in a very rural area of North Carolina, so making sure that farmers felt like their needs were addressed and making sure that they were informed about what things they were going to be feeling from the climate crisis was really huge.

Andrew Revkin

Here's a question for Sofia. If climate action seems so hard to engage on right now, if we flip the script is there a way to push forward with just the social connectedness part as a pathway forward?

Sofia Assab

That is actually what I'm writing my senior thesis on. I'm super fascinated by how taking care of ourselves is going to help us take care of the planet. As Gabbie said, so many people are already experiencing the impacts of climate change there. We don't really have a good social safety net in the United States.

You can't really think outside yourself when you're struggling to put food on the table, to pay your medical bills, to pay for college. And my thesis, my thought, is that once we do take care of those things, people's time and head space will open up and be able to look at their neighbor, look at the Earth and say, oh, we need to take care of this as well.

~ ~ ~

There's more in the video webcast, including Senator Whitehouse's frustrations with the Obama administration:

You can also watch and share our discussion on LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook.

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here.

And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues!