Exploring Extreme Winter Weather in a Human-Heated Climate

With another nor’easter brewing for the coming weekend, I hope you’ll join me LIVE today at 4 p.m. Eastern for a Sustain What conversation with climate scientists working to clarify the mix of natural variability and global warming shaping the most extreme North American winter storms.

Watch and ask questions via Substack Live, Facebook, LinkedIn, and YouTube.

It’s worth getting an update on winter storms, the jet stream and polar vortex and the rest. As I explained on social media the other day, it’s not wise to respond to President Trump’s climate-denying rage bait, but it’s worse to do so by overstating global warming’s role in winter extreme events. The science is still murky.

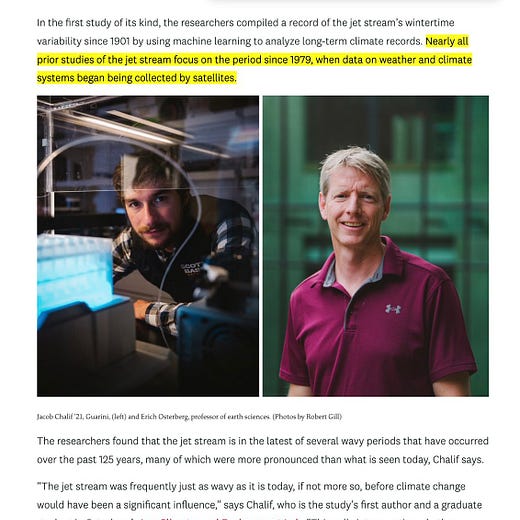

In our chat you’ll meet Jacob Chalif and Erich Osterberg, two Dartmouth researchers who are authors of the study I tweeted about above, and Mathew Barlow, who’s been on Sustain What before to discuss conditions creating “fragile states” around the world and is a climate researcher at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell.

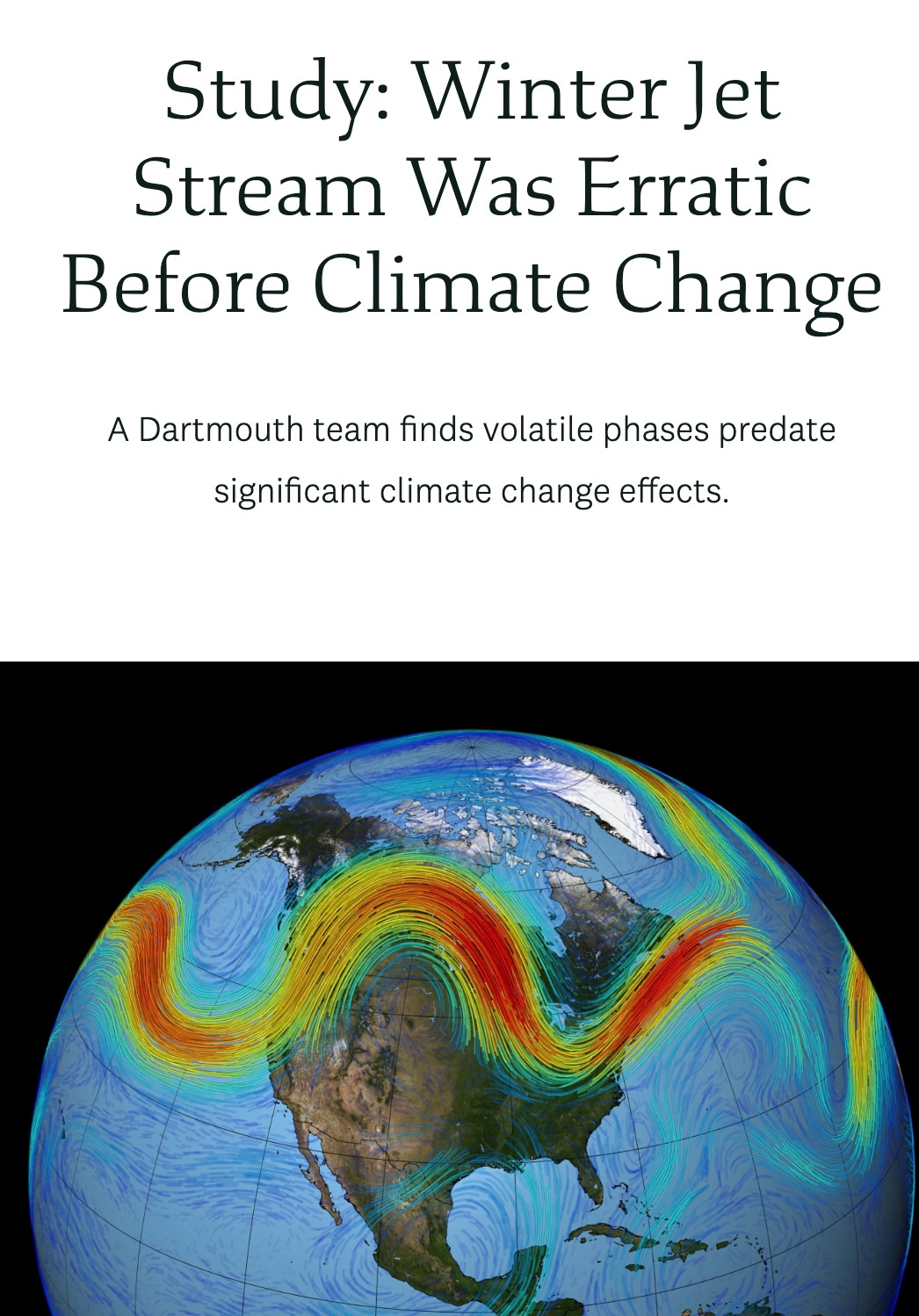

Here’s a release describing the paper by Chalif, Osterberg and a colleague: Study: Winter Jet Stream Was Erratic Before Climate Change.

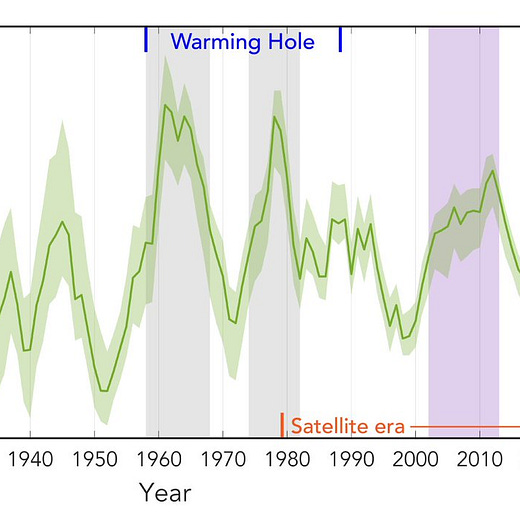

A Dartmouth study challenges the idea that climate change is behind the erratic wintertime behavior of the polar jet stream, the massive current of Arctic air that regulates weather for much of the Northern Hemisphere.

Large waves in the jet stream observed since the 1990s have, in recent years, driven abnormally frigid temperatures and devastating winter storms deep into regions such as the southern United States. Scientists fear that a warming atmosphere brought on by climate change is fueling these wild undulations, causing long troughs of bitter-cold air to drop down from the Arctic.

But a new paper in AGU Advances led by Jacob Chalif ’21, Guarini, and Erich Osterberg, a professor of earth sciences, shows that the jet stream’s volatility actually may not be that unusual. Instead, the jet stream appears to have undergone natural—though sporadic—periods of “waviness” since before the effects of climate change were considered significant, the researchers report. [Read the rest.]

Here’s a post Barlow co-wrote with meteorologist Judah Cohen for The Conversation, which I’m republishing with permission:

How the polar vortex and warm ocean intensified a major US winter storm

Mathew Barlow, UMass Lowell and Judah Cohen, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

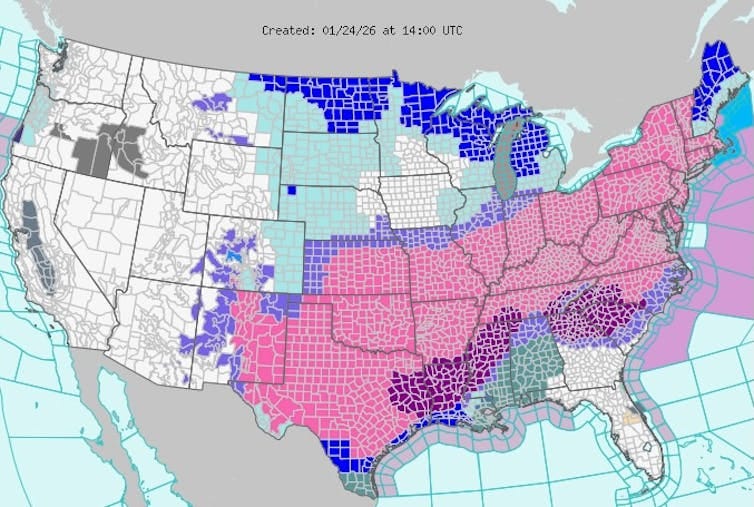

A severe winter storm that brought crippling freezing rain, sleet and snow to a large part of the U.S. in late January 2026 left a mess in states from New Mexico to New England. Hundreds of thousands of people lost power across the South as ice pulled down tree branches and power lines, more than a foot of snow fell in parts of the Midwest and Northeast, and many states faced bitter cold that was expected to linger for days.

The sudden blast may have come as a shock to many Americans after a mostly mild start to winter, but that warmth may have partly contributed to the ferocity of the storm.

As atmospheric and climate scientists, we conduct research that aims to improve understanding of extreme weather, including what makes it more or less likely to occur and how climate change might or might not play a role.

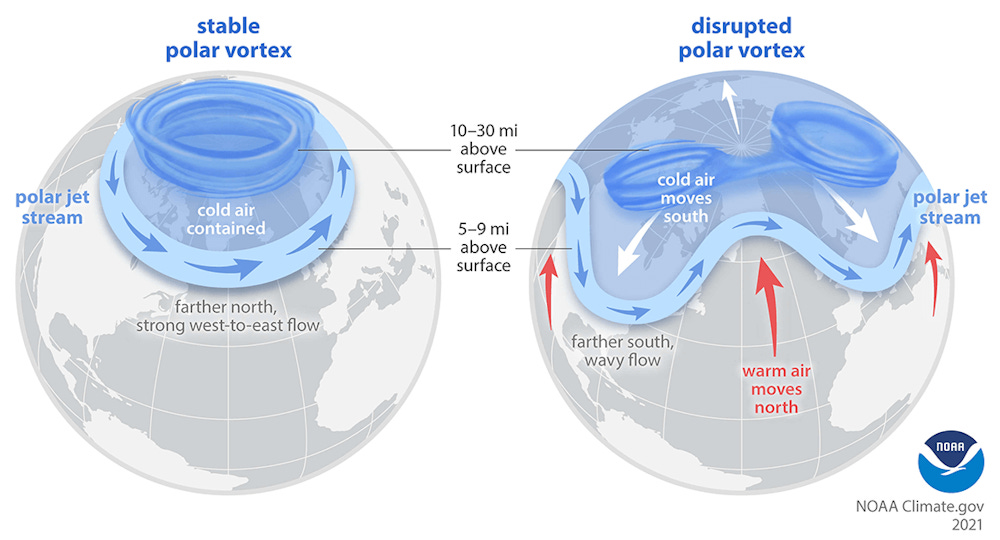

To understand what Americans are experiencing with this winter blast, we need to look more than 20 miles above the surface of Earth, to the stratospheric polar vortex.

What creates a severe winter storm like this?

Multiple weather factors have to come together to produce such a large and severe storm.

Winter storms typically develop where there are sharp temperature contrasts near the surface and a southward dip in the jet stream, the narrow band of fast-moving air that steers weather systems. If there is a substantial source of moisture, the storms can produce heavy rain or snow.

In late January, a strong Arctic air mass from the north was creating the temperature contrast with warmer air from the south. Multiple disturbances within the jet stream were acting together to create favorable conditions for precipitation, and the storm system was able to pull moisture from the very warm Gulf of Mexico.

Where does the polar vortex come in?

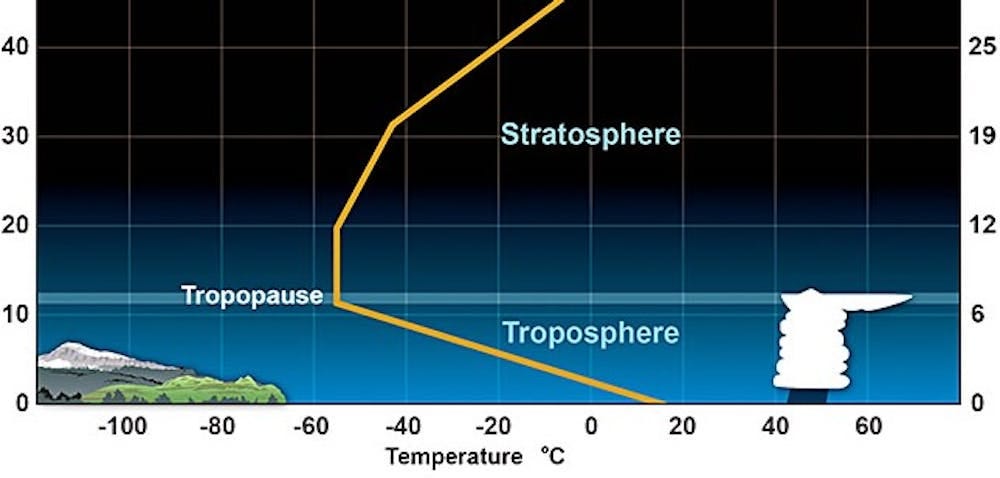

The fastest winds of the jet stream occur just below the top of the troposphere, which is the lowest level of the atmosphere and ends about seven miles above Earth’s surface. Weather systems are capped at the top of the troposphere, because the atmosphere above it becomes very stable.

The stratosphere is the next layer up, from about seven miles to about 30 miles. While the stratosphere extends high above weather systems, it can still interact with them through atmospheric waves that move up and down in the atmosphere. These waves are similar to the waves in the jet stream that cause it to dip southward, but they move vertically instead of horizontally.

You’ve probably heard the term “polar vortex” used when an area of cold Arctic air moves far enough southward to influence the United States. That term describes air circulating around the pole, but it can refer to two different circulations, one in the troposphere and one in the stratosphere.

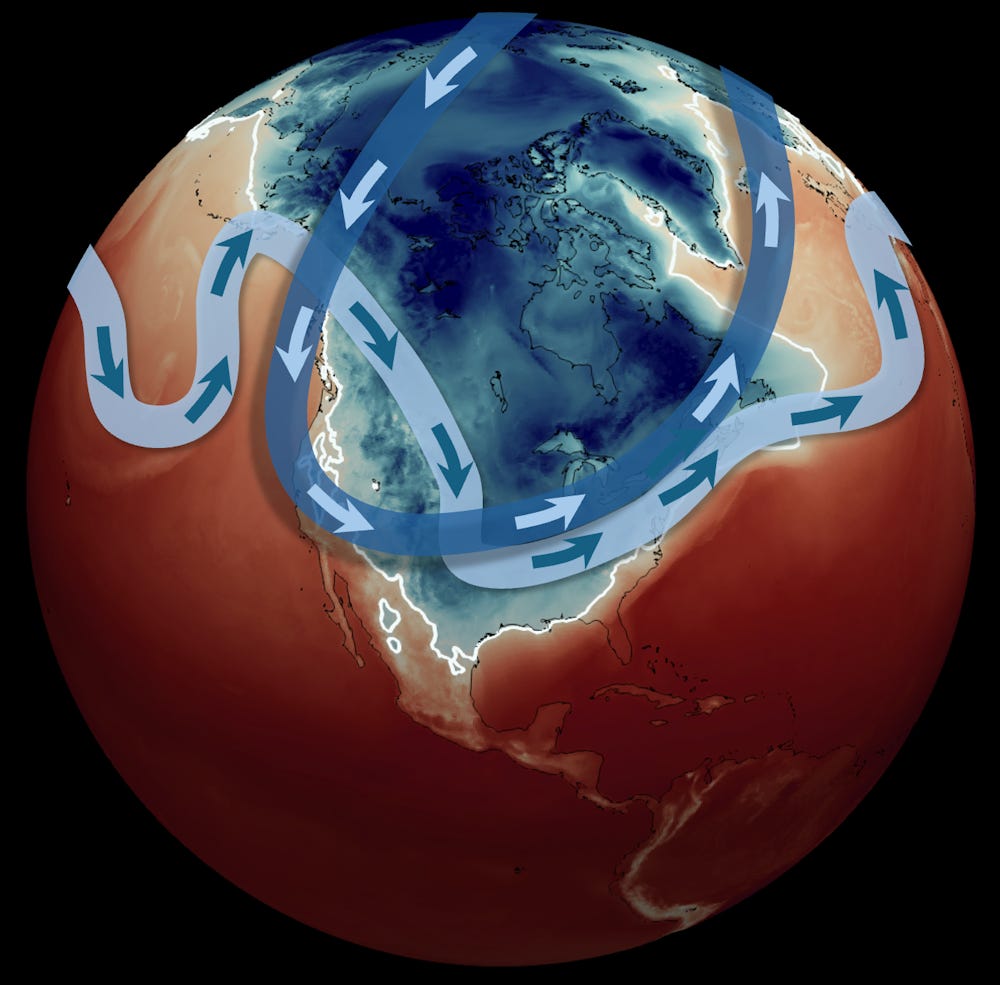

The Northern Hemisphere stratospheric polar vortex is a belt of fast-moving air circulating around the North Pole. It is like a second jet stream, high above the one you may be familiar with from weather graphics, and usually less wavy and closer to the pole.

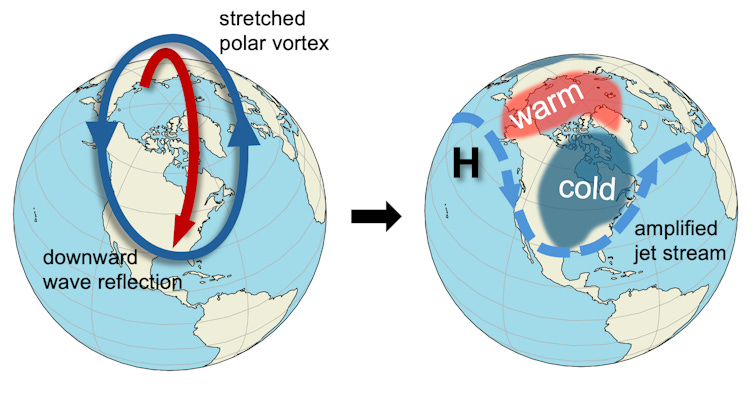

Sometimes the stratospheric polar vortex can stretch southward over the United States. When that happens, it creates ideal conditions for the up-and-down movement of waves that connect the stratosphere with severe winter weather at the surface.

The forecast for the January storm showed a close overlap between the southward stretch of the stratospheric polar vortex and the jet stream over the U.S., indicating perfect conditions for cold and snow.

The biggest swings in the jet stream are associated with the most energy. Under the right conditions, that energy can bounce off the polar vortex back down into the troposphere, exaggerating the north-south swings of the jet stream across North America and making severe winter weather more likely.

This is what was happening in late January 2026 in the central and eastern U.S.

If the climate is warming, why are we still getting severe winter storms?

Earth is unequivocally warming as human activities release greenhouse gas emissions that trap heat in the atmosphere, and snow amounts are decreasing overall. But that does not mean severe winter weather will never happen again.

Some research suggests that even in a warming environment, cold events, while occurring less frequently, may still remain relatively severe in some locations.

One factor may be increasing disruptions to the stratospheric polar vortex, which appear to be linked to the rapid warming of the Arctic with climate change.

Additionally, a warmer ocean leads to more evaporation, and because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, that means more moisture is available for storms. The process of moisture condensing into rain or snow produces energy for storms as well. However, warming can also reduce the strength of storms by reducing temperature contrasts.

The opposing effects make it complicated to assess the potential change to average storm strength. However, intense events do not necessarily change in the same way as average events. On balance, it appears that the most intense winter storms may be becoming more intense.

A warmer environment also increases the likelihood that precipitation that would have fallen as snow in previous winters may now be more likely to fall as sleet and freezing rain.

There are still many questions

Scientists are constantly improving the ability to predict and respond to these severe weather events, but there are many questions still to answer.

Much of the data and research in the field relies on a foundation of work by federal employees, including government labs like the National Center for Atmospheric Research, known as NCAR, which has been targeted by the Trump administration for funding cuts. These scientists help develop the crucial models, measuring instruments and data that scientists and forecasters everywhere depend on.

This article, originally published Jan. 24, 2026, has been updated with details from the weekend storm.

Mathew Barlow, Professor of Climate Science, UMass Lowell and Judah Cohen, Climate scientist, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Parting shot

We’ve had a spectacularly normal winter so far in downeast Maine - with a foot and a half of fluff on the ground and more coming Sunday if forecasts hold.

Roger Pielke Sr. (the meteorology luminary who is Roger Pielke Jr's dad) sent this note with some helpful references:

Hi Andy

I read your latest Substack on the extreme cold and its relationship to the atmospheric dynamics.

I taught this subject for years at both the University of Virginia and Colorado State University. It’s really quite straightforward.

The polar jet is a result of a north-south gradient of tropospheric temperatures. The larger the gradient, the stronger the jet. Also there is then more energy for extratropical storm development.

This is why the polar jet is weaker in the summer.

We have papers on this subject and I list two below.

The one that focuses on 500mb temperatures, for example, is very illustrative of long term trends and a quite modest trend

Brunke, M., R.A. Pielke Sr., and X. Zeng, 2023: Possible self-regulation of Northern Hemisphere mid-tropospheric temperatures and its connection to upper-level winds in reanalyses and Earth system models. Theoretical and Appl. Climatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-023-04635-

Wan, N., X. Lin, and R.A. Pielke Sr.: 2022: Assessment of trends in an integrated climate metric - Analysis of 200 mbar zonal wind for the period 1958–2021. Theor. Appl. Climatol., https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-022-04225-y

For my class notes on the polar jet see chapter 3 in

Pielke Sr., R.A. 2002: Synoptic Weather Lab Notes. Colorado State University, Department of Atmospheric Science Class Report #1, Final Version, August 20, 2002

This is also in the 3rd edition of my modeling book.

Pielke Sr, R.A., 2013: Mesoscale meteorological modeling. 3rd Edition, Academic Press, 760 pp. Translated into Persian in 2020.

I would be glad to discuss further.

However, the sources you quote make a straightforward atmospheric dynamic question much more complicated then it is

Best Wishes

Roger Sr