Closing the Deadly "Last-Mile" Gap Between Weather Warnings and Those Most in Harm's Way

Communication gaps like those that contributed to the horrific death toll in Texas exist elsewhere.

Several updates - If there’s one wrenching lesson to draw from the horrific and still-rising death toll in the Fourth of July weekend deluge in Texas’s Flash Flood Alley - and to consider anywhere communities live with deadly hazards - this is it:

An urgent warning is meaningless if it doesn’t reach those in harm’s way - in this case, dozens of slumbering children, camp workers and others situated along the flood-prone Guadalupe River in and around Kerr County.

The vulnerability of Camp Mystic, in particular, can be hauntingly seen on Google Maps - with the river-sculpted topography clearly making the camp a potentially deadly receptacle for high water (and a wonderful spot whenever worst-case rains aren’t falling).

Warning systems have to take into account specific situations. Some media noted, for example, that Camp Mystic’s rules for campers include a ban on cell phones, smart watches or tablets linked to the Internet. That would limit phone alerts to camp personnel. Once the recovery and mourning are done, investigations will clarify missed steps. (For contrast, watch and read this TV report on one family’s experience being roused by National Weather Service phone alerts before their campground was inundated.)

The obligation to boost preparedness and ensure responsiveness lies all along the chain from forecast to evacuation. And the challenges are as tough in the Guadalupe River watershed as they can be in tornado-prone zones. (I’ll be doing a post soon on the similarities in tornado warnings and warnings about hyperlocal deluges like this one.)

The longtime meteorologist

has published yet another valuable post indicating convincingly that the “last mile” gap was the killer in Kerr County. Here’s an excerpt from his latest update:What certainly raises alarm bells about a potential communication breakdown here is the seeming lack of awareness that Kerrville and Kerr County officials appeared to have about the flooding even as it was ongoing. From NPR’s timeline of the event:

At 5:16 a.m., the City of Kerrville's Police Department posted on its Facebook page its first warning about the weather, noting that it's a "life threatening event" and "anyone near the Guadalupe River needs to move to higher ground now." Kerr County Sheriff posted on its Facebook page for the first time about the flooding at 5:32 a.m.

At 6:22 a.m., the City Hall of Kerrville posted on Facebook: "Much needed rain swept through Kerrville overnight, but the downside is the severe weather may impact many of today's scheduled July 4th events. Citizens are encouraged to exercise caution when driving and avoid low water crossings. Kerrville Police and Fire Department personnel are currently assessing emergency needs." At 6:33 a.m. it posted about road closures due to flooding. At 7:32 a.m. it posted: "If you live along the Guadalupe River, please move to higher ground immediately."

Clearly, these actions did not start until 4 hours after the NWS issued its initial flash flood warning about life-threatening flash flooding, and goes along with the reports from a campground owner who was interviewed on MSNBC as part of an interview I did yesterday who said she called the Kerr County Sheriff at 2:30 am to ask about the need to evacuate and was told they didn’t know anything.

While all of this certainly suggests the possibility that there was a lack of the more DSS focused communication between the NWS and local officials, the local officials of course also have responsibility to have their own mechanisms to receive and distribute warnings and as of now we have no way to know where and how the breakdowns might have occurred. What we do know is the warnings were issued by the NWS and that a number of people in the area did report receiving them.

Obviously, there are contributing factors to this disaster that are more difficult to mitigate. One of my colleagues made a great point in a discussion about this tragedy today that on a holiday weekend many of the people camping along the Guadalupe River were from out of town, and may have been unaware of the flash flood danger the river posed; even if they received the warning, they likely did not have context to understand the danger. Contributing factors like this are just inherent to the various factors I have discussed that truly made this a worst case scenario. Still, there are many factors we do have control of and mitigating actions that we can take, and given that, I do believe it is important to sensitively investigate these issues in the coming days and try to learn what happened, not for political or retributive reasons, but to try to do whatever we can to ensure we mitigate the human toll of events like this as much as possible.

If there ever is a National Disaster Safety (or Review) Board, this is the kind of analysis that will be routinely done in a nonpartisan, consistent and respectful way - with the result being a safer nation. In the meantime, we all have to do what we can.

Here’s my conversation with Mike Smith, a veteran extreme-weather meteorologist who’s among a cluster of experts calling over 15 years (as a group) for a national disaster assessment process. [Insert 7/8, 5:30 pm - I’ve appended an excerpt from Mike’s new post on this vital issue at the bottom of this post.]

When Will We Ever Learn? Calls for a U.S. Disaster Safety Board Keep Piling Up

Mike Smith, a veteran meteorologist and analyst of extreme weather warning and response, has just renewed a call he’s been making since 2012 for a national disaster review board. Click here to read his original proposal (part 1, part 2).

Inserted July 8, 3 p.m. ET - I had missed

’s valuable post asking why campgrounds were in such dangerous floodplains:Original continues - Here’s more on the lagging local efforts in a region facing profound, but rare, worst-case dangers from extreme local downpours.

You’ve likely seen the latest reporting from the Houston Chronicle, New York Times and others on rejected or delayed Kerr County plans for sirens and other systems.

CBS’s Texas team reported:

Nearly a decade ago, neighboring counties, Guadalupe and Comal, installed flood sirens. Nearby New Braunfels regularly tests its outdoor warning system, which is designed to alert residents to flash floods that are common in the area.

But in Kerr County, officials admitted over the weekend that no such system exists. County commissioner records show that in 2017, Kerr County officials considered installing a warning system but ultimately rejected the idea. Cost was a major concern.

In an August 2016 commissioners court meeting, then Commissioner Buster Baldwin voted against a $50,000 flood engineering study saying, "I think this whole thing is a little extravagant for Kerr County and I see the word sirens and all that stuff in here."

Efforts to address the issue at the state level have also stalled.

Texas House Bill 13, introduced in the most recent legislative session, would have created a statewide strategic plan for outdoor sirens and help fund sirens in rural areas. The bill failed to pass amid criticism over its price tag.

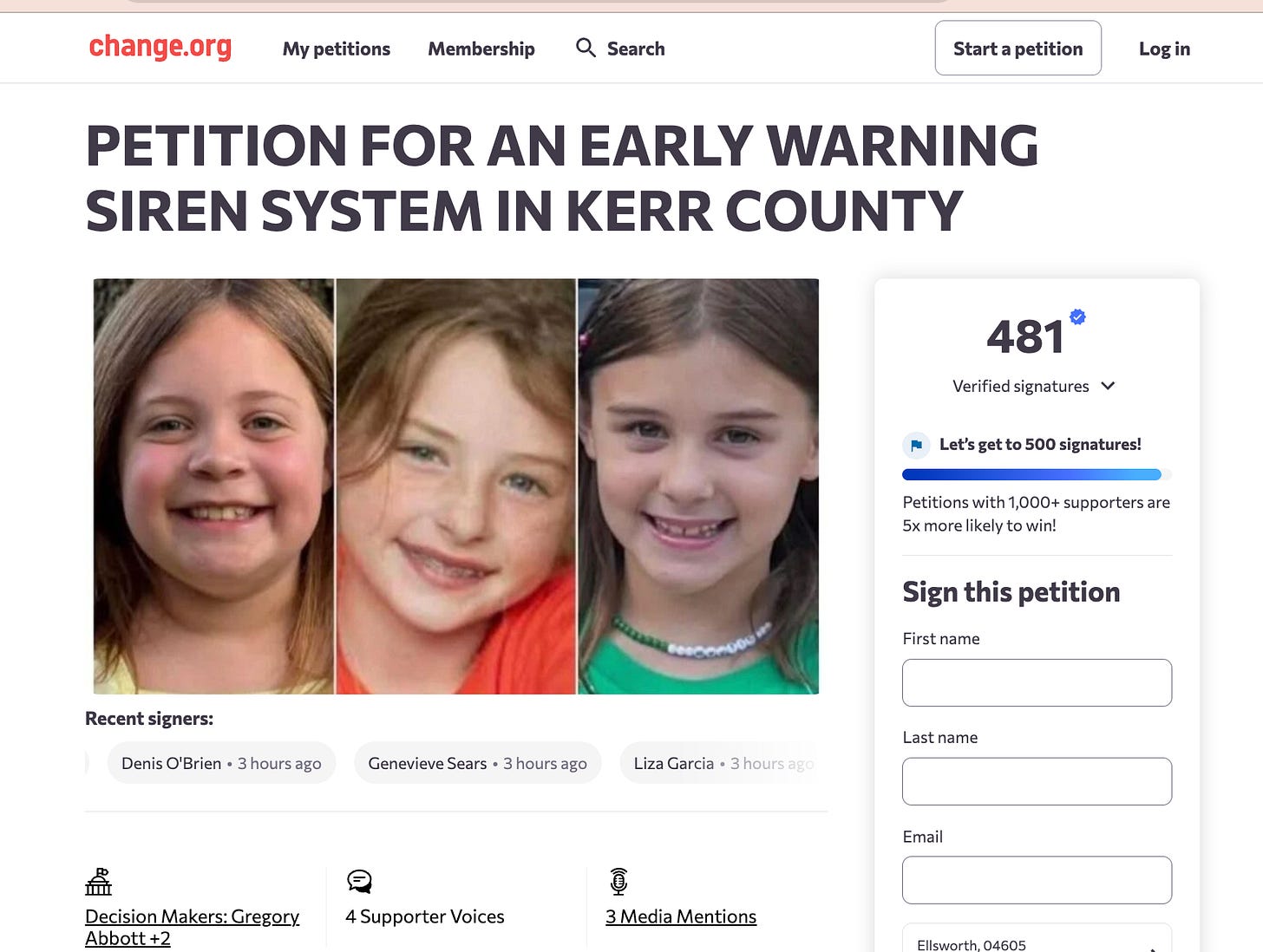

A Change.org petition organized by Nicole Wilson, a San Antonio resident who grew up with siren warning systems in Kentucky, lays out the logic and makes a solid case for action.

We, the undersigned residents, families, and concerned community members, urgently call on the City of Kerrville and Kerr County Commissioners Court to implement a modern outdoor early warning siren system for floods, tornadoes, and other life-threatening emergencies.

The tragic events at Camp Mystic and the devastating flooding along the Guadalupe River that happened in July are stark reminders that severe weather can strike with little notice. A well-placed siren system will provide critical extra minutes for families, schools, camps, businesses, and visitors to seek shelter and evacuate when needed.

This is not just a wish — it is a necessary investment in public safety. Early warning sirens have saved thousands of lives in other communities by giving clear, unmistakable alerts day or night, even when cell phone service or electricity fails.

We respectfully ask that city and county officials:

1. Make it a top priority to develop a plan and cost estimate for a reliable outdoor warning siren network.

2. Apply for all available funding, including FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grants, USDA Community Facilities Grants, and other state or federal resources.

3. Include local residents in the planning process so the system meets the real needs of our neighborhoods, camps, schools, and businesses.

We believe this is an achievable, commonsense step that can save lives and help protect our community in the face of future floods and severe weather. Please act now — we cannot afford to wait for another tragedy.

The photo included are just three - THREE! - of the missing girls of more than 20 from Camp Mystic. This doesn’t include the countless residents, visitors, campers, etc. that are still missing.

To get some clarity amid the megaflood of online debate over the still-unfolding disaster, sign up for UCLA weather scientist Daniel Swain’s briefings. Here’s his most recent update:

Postscript

As promised here’s an excerpt from the latest post by extreme-weather warning expert Mike Smith on the need for a National Disaster Review Board (others call it Safety Board):

[F]ind more information about the proposed National Disaster Review Board (NDRB) and how it will function here and here.

The State of Texas has suffered nearly 1,200 flood deaths – most in the Hill Country – during the past 55 years. That number is staggering. This past autumn, we lost 249 souls because of Hurricane Helene. In 2011, 161 were killed because of a single tornado in Joplin, MO. National Weather Service tornado warnings are much less accurate than 15 years ago. These, and much more, need understanding of the issues and then repair of the same as mega-disasters may be increasing.

With regard to the Texas floods and riverside camps, here is a partial list of questions that need to be answered:

· What procedures did the camps have in place for floods (and, while we are at it, tornadoes)?

· Were those procedures practiced? By whom: staff, staff and campers?

· How were weather warnings received?

· Did the staff understand the types of warnings (flood, flash flood, flash flood emergency)?

· Was a dam in the area that made the flood worse?

· Did the WEA smartphone warnings trigger on a immediately or was there a lag?

· Is it possible to satellite-to-smartphone communications to send out weather warnings in the way they are sent using the cell network now?

Again, these are just examples of the questions that require answers. Once the NDRB investigators of have done their work, a preliminary report will be drafted. Then, a public hearing will be held so that the parties (victims, first responders, camp owners, National Weather Service, etc.) will have input. Then, the final report along with recommendations for fixing the issues will be published. This is very similar to the method used by the highly successful National Transportation Safety Board.