Can There Be Passion and Detachment in Environmental Journalism?

This essay lays out my approach to environmental journalism in this age of consequential complexity and click-seeking news as noise

I want to give newcomers to my journey a bit of context on why I got into journalism nearly 40 years ago and how I pursue this practice. I first posted a version of this lecture summary in 2010 on my Dot Earth blog at The New York Times but want it to be outside the paywall here as well. Weigh in with your reactions.

To you, what is journalism for these days?

IN 2005, I was invited to give a lecture at Willamette University in Oregon explaining how someone can cherish the environment while remaining sufficiently detached to retain journalistic integrity. The talk was given as part of a discussion featuring Terry Tempest Williams and including Dale Jamieson, Ed Begley, Jr., Jane Lubchenco, Dave Foreman and others.

As you read, keep in mind this talk was given while I was still a full-time Times news reporter — before my Dot Earth blog moved to the Opinion side of The Times in 2010. Here goes….

I WAS THANKFUL for the invitation to come to Willamette mainly because of the question that was posed to me. It wasn’t just, “Talk about the challenges facing the media or the state of the world.” It was personal, powerful and unexpected, the kind of question that people like me ordinarily sweep under the rug:

How does a reporter, whose job covering the environment requires dispassionate detachment, reconcile those constraints with the passions and points of view that inevitably emerge in a fully lived life?

First of all, I’ll prove to you that I am in fact a person first and a writer second, by filling you in a bit on how I got into this line of work.

Essentially, I’ve backed into my reporting life. I did not come out of the womb, like most of my colleagues, with a pen and notepad in my hand saying, “I’m going to be a newspaper reporter someday.”

I was drawn first to the sciences. I was born, raised, and educated in Rhode Island, where I spent a lot of time in winter following rabbit tracks in the snow and, in summer, sailing and snorkeling along the shores of Narragansett Bay, watching scallops clap their shells in their amazing underwater castanet dance. I caught, cleaned, and cooked the occasional flounder. I stomped on low-tide mud flats to elicit the squirt of buried clams. That’s where my love of nature began. I also loved to read about people learning to live with nature, both in fiction and nonfiction. Almost every time I had to stay home from school, I ended up re-reading The Swiss Family Robinson — which hypnotized me with all those descriptions of giant lobsters and snakes. Later I would move on to The Voyage of the Beagle.

Killing a songbird

My appreciation for the power human beings wield through technology and wile grew as I approached adolescence. One winter when I was 12 or so, a friend invited me over to his house to try out his BB gun. My dad had one on the small sailboat we cruised around in during the summer, which we used to perforate tossed soda cans so they would sink to the seabed (recycling had not become a movement yet). This time, as Doug and I crouched on the cement steps leading up from his basement to the back yard, we had a different intent. We took turns aiming at the chickadees and titmice that flitted in the trees and on a clothesline strung between two branches. I pulled the trigger. A ball of feathers fluttered wildly and fell to the snow, flinging flecks of blood and down in every direction on the whiteness before it lay still and died. Every detail of that little murder was welded indelibly in my brain. I have great respect for the hunters I know who hone their woodcraft carefully and shoot to kill — and eat. But after I shot that bird, I never shot at a living thing again.

Writing a death threat

My passion for environmental protection began around the age of 14, when I hiked into the small patch of woods and fields that remained untouched in the expanding suburban grid of streets and lawns around our home and discovered a bulldozer parked in a fresh-cut clearing near my favorite spruce tree.

I placed a hand-lettered warning sign on the seat that read something like: “Whoever chops down this tree will suffer a horrible death.”

[Reflection: When I saw the bulldozer, and even when I gave this lecture, I hadn’t yet absorbed the irony that I had no concern for the bulldozers that had — perhaps only a decade before — cleared the woods when our suburban housing development was built. More on that angle is here.]

Beyond my love of nature, I developed a passion for science in high school, largely through the unorthodox educational efforts of two biology teachers, Joe Laterra and Joe Ferretti. Their subversive approach was to let us actually do science instead of just learning it. We studied a salt marsh with state wildlife biologists. I built a wave tank in the back of Mr. Ferretti’s classroom, adjusting a small electric fan and a cardboard baffle and other elements until I generated miniature breakers foaming on a mock beach.

Through junior high and high school I enjoyed writing but did not see it as my calling. The only newspaper I worked for until I was an adult was a mimeographed satirical, political, outlaw rant at my high school called EGAD, for East Greenwich After Dark. It was the antithesis of good journalism — all innuendo and barbs.

A despairing optimist

I went to Brown University, where I first read the essays of Rene Dubos and appreciated that a human-altered landscape was not necessarily a bad thing, and also that it was possible to have a positive attitude even in the face of daunting data on the adverse impacts people were having on the planet. His title for a regular column was “The Despairing Optimist,” and I have since happily adopted that label for myself.

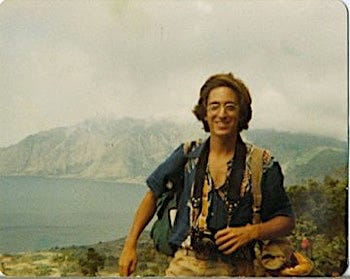

I graduated in 1978 with a biology degree and was lucky enough to win a traveling fellowship that allowed me to get out into the world beyond New England — far out. My proposal was to go to small islands in the South Pacific and study “man’s relationship to the sea” (yet another echo of those Swiss castaways!). In a tiny unwired village at the end of an unpaved road ringing the splendid French Polynesian island of Raiatea, I experienced the Rousseau-like ideal of people living simply, in harmony with nature.

But the community was in transition even as I settled in, and the Tahitian friends I made there were clearly eager to move from subsistence to a modern consumer existence. I would return 10 years later and see the consequences of development, for better and worse. I also began to realize that, however I might feel about their rush to modernity (frozen tuna replacing fresh caught), I had no right to argue against it.

Read my 1989 feature story in Islands Magazine about my Return to Raiatea here:

At sea

I was lucky again. In Auckland, New Zealand, near the end of that project, I saw a sign on a marina bulletin board that said: “Crew Wanted, Yacht Wanderlust; inquire Marsden Wharf.” I ended up becoming the first mate on the 60-foot home-built American sailboat, which was headed around the world. I lived on board for 17 months and we visited 15 countries in 15,000 miles of cruising.

That trip made me want to tell true stories in words and pictures — to be a journalist. I saw and experienced so many wonders along the way, particularly the simple splendor and power of the open sea, that I had to share it all.

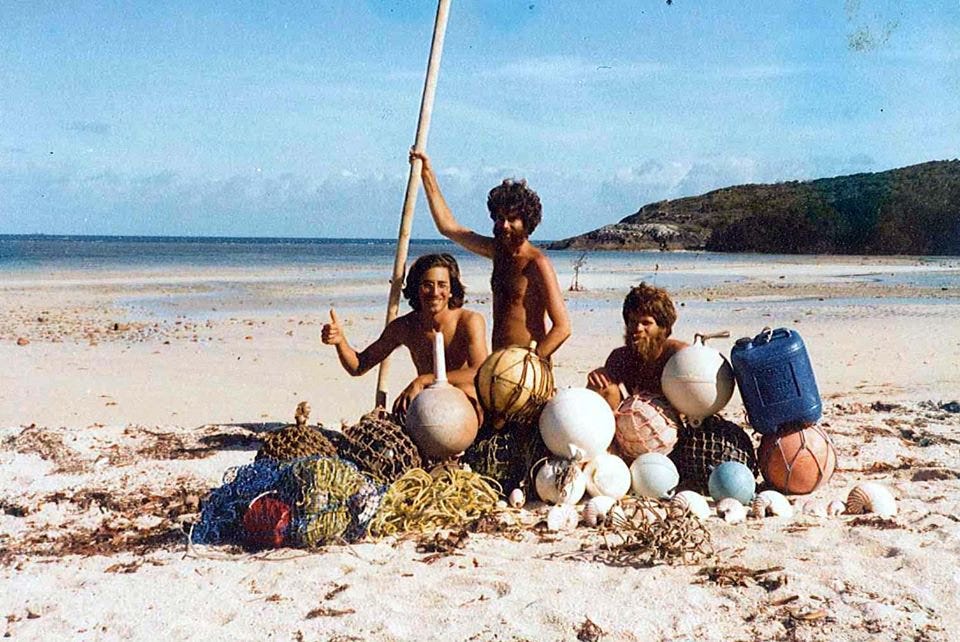

There were also disquieting moments, as when, early in 1979, we anchored for a couple of days at Mount Adolphus Island, tucked between the Australian mainland’s northernmost point and Papua New Guinea. Three of us explored the uninhabited beach, collecting a heap of plastic flotsam - mostly fishing gear. That day sticks in memory as I ponder today’s plastics crisis.

Something of an epiphany occurred almost a year later as I hiked across a deserted island in the Red Sea and found the windward shore heaped with intact light bulbs. There were all manner of long fluorescent tubes and spotlights and conventional incandescent bulbs lying just above the tide line. It took a moment for me to realize they must have washed there one by one, year after year, probably after being tossed overboard by crewmen on passing ships. This was the first time I really appreciated the power of people to change the world in unintended ways. (In 1998, I wrote an essay for The Times about this odd kind of lightbulb moment.)

Eventually, as happens to everyone who tries to circumnavigate, I came to realize the world actually was round, meaning you inevitably end up pointed back toward where you began. It was time to go home. After seeing extraordinary poverty in places like Djibouti and the wealth of nature in places like the Great Barrier Reef, I just had to tell everybody about it. I tried writing some magazine articles, largely failing. I traveled to Washington and excitedly showed my photographs to an editor at National Geographic, including this one of a pile of leopard skins for sale at a tobacco shop in Djibouti, then a French protectorate seemingly populated mainly by Foreign Legionnaires.

He really liked my eye for an image, but noted that my astigmatism made an awful lot of the shots just the tiniest bit out of focus — and unusable. Maybe there was something about this craft that I actually had to learn, I realized.

I learned journalism basics back in school, at Columbia, and then in a series of jobs as I climbed the profession’s rungs, from copy editing to writing to assigning articles to writing books and finally to working for what remains arguably the world’s best newspaper — for all its many faults.

All along the way, I settled into the world of journalistic norms. A story has an unavoidable structure. The lead tugs the reader in. The “organ music” or “nut paragraph” tells the reader why an article is important. Balance assures that you’ve avoided tipping your own hand about what you think or feel about the subject at hand.

In the process I learned to put away my old notions of self, of ego and attitudes. Journalism is probably the purest example of a calling in which you have a discontinuity between the personal and the professional. You are literally not allowed to exist as a person (unless you are a columnist like Tom Friedman or George Will or Dave Barry or write first-person accounts for the New Yorker… unless you are expressly, overtly you).

Nowhere is the selflessness more profound than when you work for an institution like Time magazine or The New York Times. You are clearly part of a bigger machine. Newspapers have started to loosen up in how they let writers write. The Los Angeles Times, where I worked briefly in the mid 1980’s, was more of a writer-friendly paper. Stories could unfold at a leisurely pace, allowing room for reported “moments” that help build a picture in the reader’s mind. In contrast, at The Times, almost like clockwork, memos are circulated one every other year or so admonishing us to write shorter, and shorter yet. Several layers of editors examine each story before it is printed, not only making sure it is comprehensible and correct, but also that it is in Times style, which does not always mean it is in the writer’s style.

Being “right for a day” is not enough

Sometimes I have found the process exasperating, even dehumanizing, but over my 11 years (and counting) at the paper, one passion of mine has been preserved, and that is the one that drives me every day: my passion for the truth. Of course, there is no truth, really, just a trajectory toward understanding. Any article that implies it presents the bottom line on some issue is probably being dishonest. Too often, journalism aspires to being “right for a day.” The facts in a story can all be correct, but it can still distort understanding. That pressure in journalism derives partly from the competitive nature of the business (we desperately want to be the first to say something is so), and the fact that it is, in fact, a business. We have an ingrained tendency to sift for the “front-page thought” in a pile of news that we have absorbed in the course of a day and — without a stiff dose of discipline — this can tempt even the most professional reporter or editor to tilt things just a bit toward hyperbole.

In instances like that, passion can drive a story over the edge. While it might get better “play” the next day and catch more readers’ attention, in the end the process bites back. Think of how many stories you’ve read over the years about coffee and health. One minute coffee is a threat, the next it’s a benefit. Major magazines and papers ran cover stories and front-page stories proclaiming that electromagnetic fields were associated with cancer, and then ran stories when subsequent studies found the risk was unclear, if there was one at all. Read more on what I call “whiplash journalism.” Here’s a little card I made as the social media flow intensified this phenomenon. I hope you’ll deploy it when you see examples:

To some extent this process is merely mirroring the eagerness of society, generally, to crave clarity and recoil from uncertainty. But the media amplify and help perpetuate that swinging pendulum, to my mind. We reporters are not always careful to tell how much we don’t know along with how much we have learned. And that can be as important sometimes, whether we’re writing about hints of unconventional weapons in Iraq or Alar in apples.

Finding the right approach can be incredibly exasperating to a science writer, and it is passion for the larger truth that pulls us forward. Not long ago, I saw frustration build in a colleague, the veteran medical writer Gina Kolata, as she grappled with a new paper in a respected journal, Science, positing that farmed Atlantic salmon held much higher levels of PCBs and other contaminants in its flesh than did wild salmon. The authors calculated that the risks from these chemical traces meant consumers should not eat more than one salmon meal a month despite the many health benefits conferred by such fish. The Food and Drug Administration, noting that the detected concentrations were dozens of times lower than federal limits, strongly disagreed. Some top toxicologists not aligned with the seafood industry or anyone else also fervently disputed the researchers’ risk calculation.

Gina wrote a clear piece that explained the new findings. At the last minute, to make sure hurried readers put things in perspective, she added a vital extra clause to the opening sentence (the italics are mine): “A new study of fillets from 700 salmon, wild and farmed, finds that the farmed fish consistently have more PCB’s and other contaminants, but at levels far below the limits set by the federal government.”

Even with that proviso, and a host of researchers’ voices further down in the story stressing that the health benefits of eating salmon were far clearer than any small risk from PCBs, readers remained confused. Salmon piled up in some supermarkets. The situation was sufficiently confusing that my brother, a cardiologist and heart-drug researcher, sent me an urgent e-mail asking:

“What’s the poop on the risk of farmed salmon, dioxin and PCBs? Any truth to it? I eat it as much as three times a week.”

I’d covered PCBs for years in the context of the remaining stains buried in the Hudson’s river-bottom mud. My own instinct on this, which I conveyed to my brother not as a journalist but simply as a citizen who has had to make judgments in the face of uncertainty, was that he should eat and enjoy (while perhaps avoiding the brownish fatty tissue and — sad to say for sushi-roll lovers — the salmon skin).

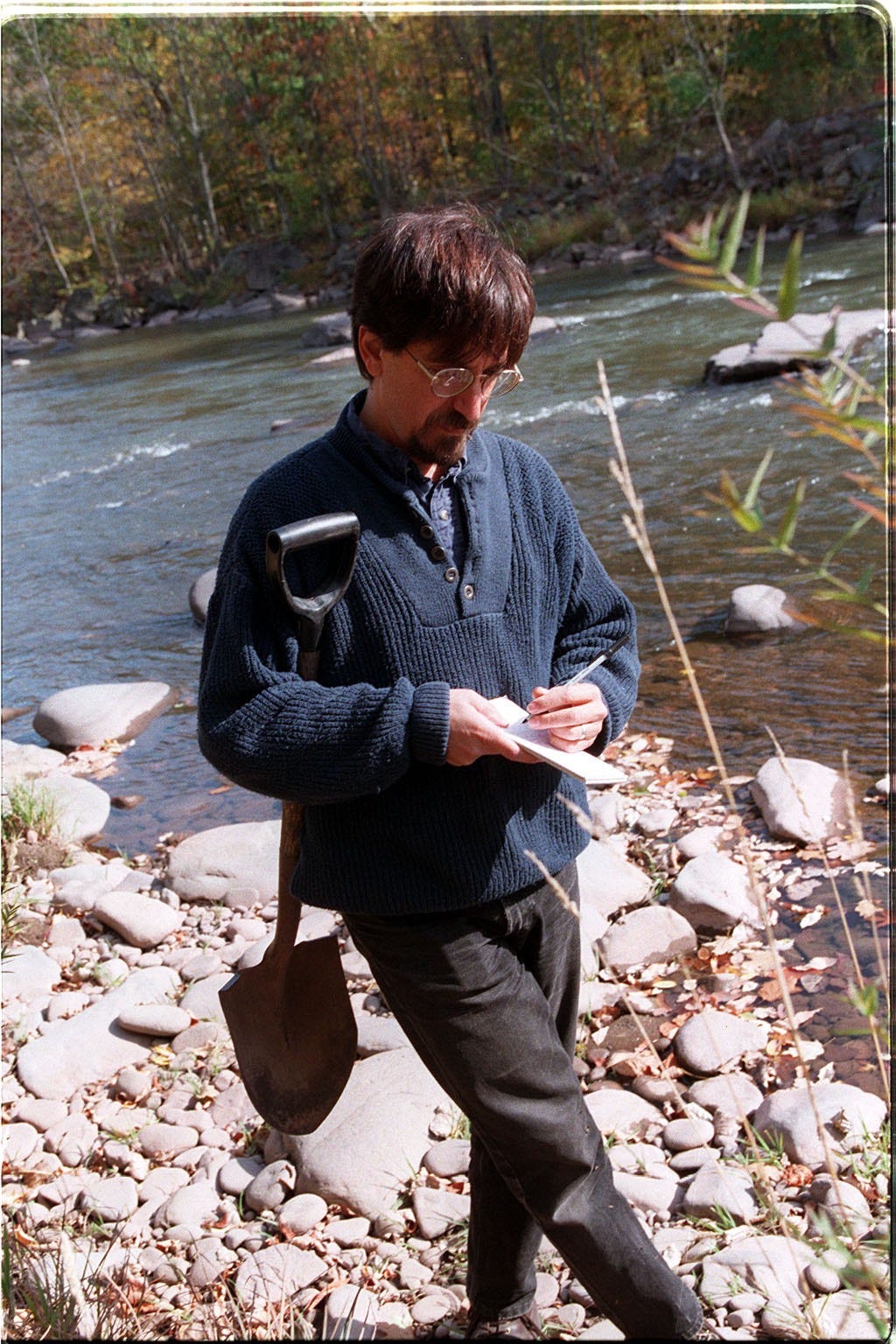

There are more profound challenges in the news business. Newspapers are still mainly, and unsurprisingly, a means for informing the public about things that are different today than yesterday, and important today, not someday. That means that slowly emerging problems — think sprawl, think the millions of gas-station drips that add up to 1.5 Exxon Valdez tankers a year, and definitely think global warming — often fail to get the space that they probably deserve.

In my first four years at The Times, I wrote dozens of stories about efforts to preserve the quality of New York City’s water supply — 19 reservoirs surrounded by 2,000 square miles of rapidly developing exurbs — without having to build a giant filtration plant. I spent a couple of months reporting what we call “a heave,” a big special report on the looming pollution problems that were slowly threatening the water. At the last minute, an editor looked at the length of the story and said, “Isn’t this a little ahead of the news?”

That, sadly, is a direct quote. I was kind of stunned. I figured it was our job to be a little ahead of the news. And it seemed suddenly like maybe that wasn’t necessarily the case. The story survived, albeit cut back, but it nearly got bumped entirely from the front page by the news that Princess Diana had died in a car crash.

No story is less like news than my current stock in trade, global warming. It is the antithesis of news, yet my passion keeps forcing me to write on it, and push to get it space in the paper. For many years, getting the paper to grant space for a story on a significant advance in climate science was something like trying to get an elephant into a Prius. A newspaper is mostly set up to talk about what happened today, maybe sometimes what may happen tomorrow, but not what is going to happen over the course of a century.

I don’t see much prospect that I or some other writer will suddenly figure out a new way to tell this story that will magically make it fit into the 20th-century template we still use to decide what is important or newsworthy, and thus galvanize the public to care.

No matter. I’m going to stick with my own sense of what’s important, and I’ll keep telling those stories in whatever medium is handy. Here’s where passion comes into a reporter’s life. Newspaper writers, except when faced with breaking news, largely sustain their own lists of stories. We all make choices in doing that.

I make my story choices these days based on irreversibility: what problems are emerging that cannot be undone on time scales relevant to human affairs?

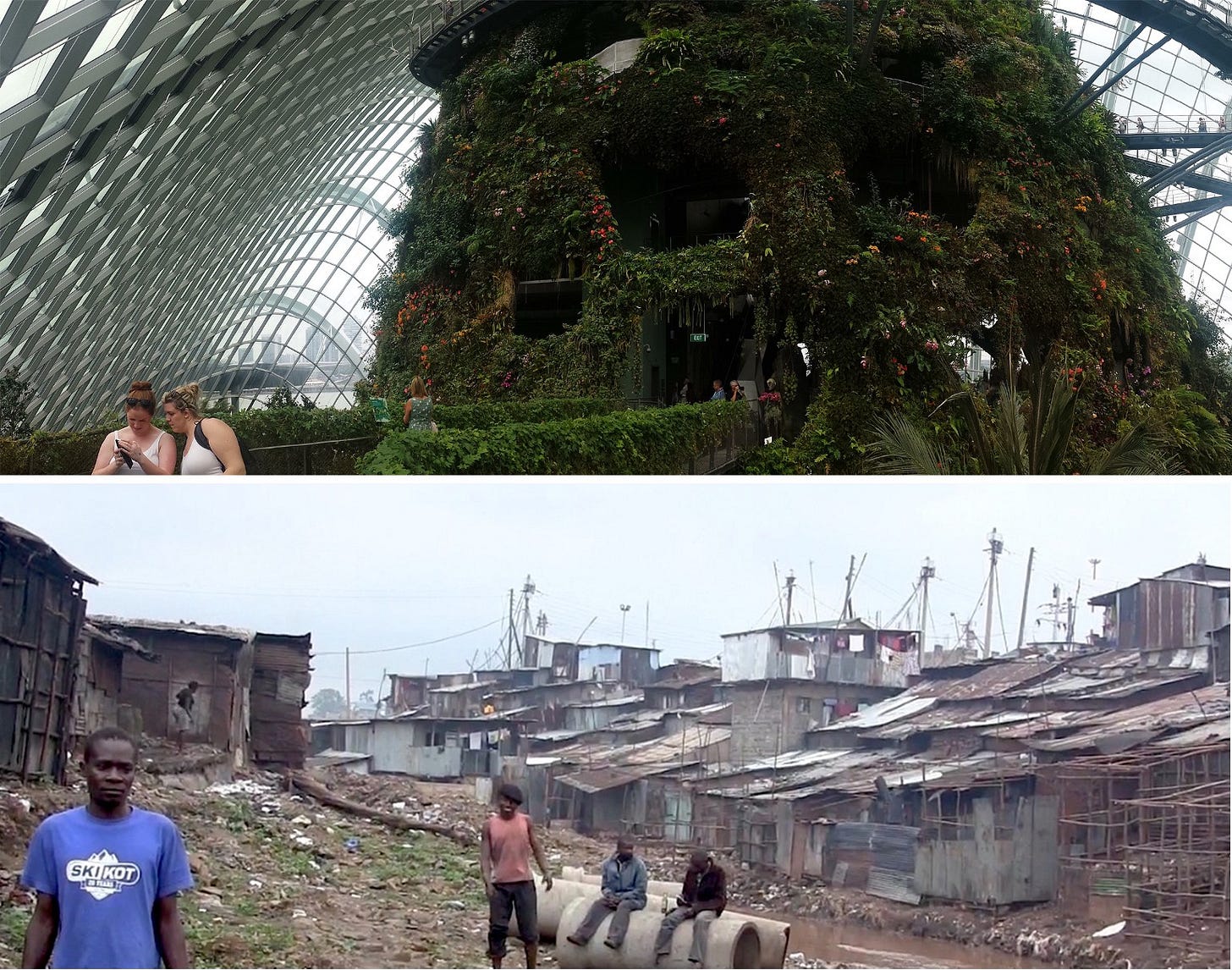

The list is short: human-caused global warming, the loss of biodiversity and wilderness, and large human losses from avoidable causes (like predicted floods of sub-sea-level cities; like waterborne disease and the 1.6 million premature deaths occurring each year from mainly women and children inhaling choking plumes of smoke from unvented indoor cooking fires).

I may well be the only reporter at The Times who thinks of a century-scale story, the saga of global warming, as breaking news. My impression is that some of my bosses still don’t get it, but they kind of let me keep at it, in the way that a family tolerates an eccentric uncle with odd habits.

My hope is that, slowly (but hopefully not too slowly), humans will grow through their longstanding reliance on those age-old “fight or flight” reflexes that served us so well on the savanna but may not suffice any more.

Our norms, our values, our gauges for measuring costs and benefits, these are the things that would have to change.

While I have spent most of my career writing about science, I’m shifting a bit of late. I’ve become more convinced than ever that some new scientific finding is not what will trigger change. Science is always going to provide ammunition to everyone in the debate — the naysayers and the apocalyptics and the people in between — because science is like that. It is murky. It is multifaceted. Climate science, especially, is saddled with inevitable, unavoidable uncertainties. We all kind of proceed, in the political discourse and the media, as if some new breakthrough will suddenly make it all easy, will clarify how much global warming is too much. Many of us, and not just people tied to industry, see uncertainty as a reason to wait, to do more research. Others see the same uncertainty as ample reason to proceed with caution now that we know we are altering the atmosphere in ways that are ratcheting up the planet’s thermostat, even if we don’t know the details.

Different minds, different views of risk

But no one can ever expect to see a headline in The New York Times reading: “Global Warming Strikes. Seas Rise. Coasts Flood. Crops Fail. People Flee.” All of those things are likely to play out if the world does not find a way to stop emitting greenhouse gases as the global population goes to 10 billion or so and rich and poor nations continue to grow their economies. But they will be dispersed in time and geography, constituting the ultimate slow drip.

What this debate will swing on, ultimately, is the softer stuff –- things like evolving values. How much does one value the quality of a child’s adult life? But values and ethics are not the stuff of a hard news story, either. Perhaps they are even less of a story that climate science! [Also read “When Data and Values Met at the Vatican.”]

Nonetheless, I’ve started focusing on that side of things. I wrote a long story in 2005 on efforts by various countries to shift from purely economic measures of progress, like gross domestic product, to broader ones, like Bhutan’s notion of “gross national happiness.” There, the country is seeking to weigh economic, environmental, cultural, and social factors together as a barometer of wellbeing, not simply growth. The move is inspired partly by studies of wealthy societies that show when a country grows through a certain level of basic prosperity more money does not make people more content.

My prediction is that such efforts will spread. This is likely to be a groundswell that will eventually overwhelm the kind of hard pencil-pusher notion that can be summarized as: “Oh, future generations are always going to be richer and smarter than we are and so they don’t need our help right now.”

All I can say is that I hope we can find a way through this sort of bottleneck we face. Humans are at this great moment in their cultural evolution, a point when we have begun to recognize that we have in many ways become a planet-scale force. How do we increase the human population by another 50 percent in the next 50 years and come out the other side without diminished possibilities for our successors? I think there are unavoidable losses coming, but many rich prospects will remain.

Somehow, even as we get up in the morning, knowing the scope of the challenge, we have to find a way, at worst, to limit losses and, at best, to make the world a little better than we found it. And we also have to find a way to forgive ourselves for the adolescent exuberance that got us into this fix.

Rene Dubos’s notion of the despairing optimist once again comes to mind. Some of that sensibility is reflected in a Portuguese word that a comparative literature professor of mine used to talk about. The word is saudade. It describes the sadness and happiness of reflecting on something cherished that has been lost and might someday be found again. It is a word you’d use to describe the feeling, say, in a Dublin pub around 1 a.m., when patrons are all singing a lament with great smiles on their faces, and tears.

It’s kind of like simultaneously sustaining passion and detachment — those qualities in a decent journalist.

We are at a stage of social history not unlike where I was, as an individual, back in 1968, after I watched that little bird die on the snow. That was the first time I really internalized my power to change the world, for better or worse. I adjusted my behavior from that point on. I grew up a little that day.

The question posed to humans now is the same. We are in a race between potency and self-awareness, kind of like the juncture between adolescence and adulthood.

The question we face now, and that I will be writing about until I can’t write any more is this:

What do we want to be when we grow up?

I lived in American Samoa for a while in the mid ‘80s, a stunningly beautiful island. I remember one day snorkeling along a rocky portion of beach and coming to a very small sandy section, only to find a bunch of plastic water bottles and disposable baby diapers washed up onto the sand. I learned then what your experiences show, which is that it is largely the people living in material security who focus on environmental issues.

This is clearly shown in a large global 2014 UN developmental priorities survey, where in poor countries energy security ranks far above climate change as a major concern--- climate change ranks dead last. In rich countries where people are living in energy security, climate change ranks as a major concern.

Scientists, policy makers, journalists use the word “we” a lot when discussing solutions to climate change--- we need to decarbonize, “ we have to find a way… to make the world a little better than we found it”, “what do we want to be when we grow up?” My point is that this inclusive sounding “we” is really the discourse of the energy secure stratum of the global population.

Passion vs. Detachment? The word that occurs to me is Balance.

It is the day after Thanksgiving 2022 and I am reading your story of how you evolved into the person as journalist and I am appreciating the reflection on the past decades of your life on the climate beat, especially the challenges of working under The Old Grey Lady. You shared about learning the Portuguese/Brazilian term "saudade" and I resonate with that. Just last night I read an article in The Big Think about the Swedish word, "lagom" which is definitely a concept that needs to be put into our human reality. I think I want to be Goldilocks when I grow up. Give me a few more weeks during these American consumer holidays to adapt. And as you have referenced Emerson, we need to fall forward without falling down. Thanks for exposing the uncertainty and risks we face in our world. Here is the article about lagom. https://bigthink.com/thinking/swedish-philosophy-lagom-just-enough/