Behind Global "Climate Emergency" Rhetoric, Solvable Local Vulnerability Emergencies Abound

Rich-world climate impacts - explosive wildfires, deadly urban floods and heat domes - are terrible. But this phrase obscures a profound vulnerability divide among and within countries.

Various updates

A deadly vulnerability emergency hides behind the vague, even paralytic scale of a phrase like "climate emergency." (Listen to longtime climate-impacts researcher Mike Hulme here for more concerns about #climateemergency proclamations).

The vulnerability emergency can be right down the block from you - in a home where an elderly couple can't afford air conditioning; or in the supply chain leading from the blueberries in your fridge to the dangerously baking fields where they were harvested; or in many parts of Africa where flooding is so common it misses the headline cycle.

Some vulnerability is essentially designed and built. Disaster researchers Jon Barnett and Saffron O'Neill coined the term "maladaptation" to describe this bad human habit. [Insert 10/22/22: In a comment below, disaster researcher Ilan Kelman says this term goes back much further.]

That's what was devastatingly on display in 2021 in Blessem, Germany (the photo at left above), where a sand and gravel pit excavated next to a town in a floodplain helped funnel disastrous (but not unprecedented) floodwaters.

But most of the climate vulnerability driving deaths and community devastation in flooding around the world, even as overall death rates from flooding and the like have declined, comes from more profound and troubling systemic factors.

Tens of millions of people have surged into climate-hazard hot spots in the last couple of decades, according to a building body of research, defying much-publicized projections of a mass surge of people away from such places. And that surge explains far more of the losses being experienced right now in climate disasters than the change in the climate system from our emissions of greenhouse gases.

I explored how exposure to flooding has surged in a post on an important new paper showing this counterintuitive reality using vast amounts of satellite imagery and population data.

We dug deeper on these issues in a Columbia Climate School Sustain What session with innovators, scientists, financial and experts from around the world - including a Bangladesh-based all-of-the-above climate doer, Saleemul Huq.

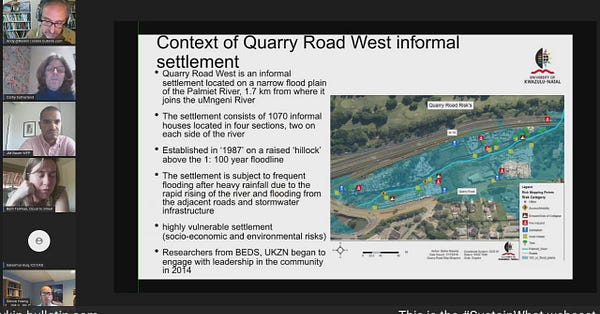

You can watch on YouTube, LinkedIn and Facebook and also on Twitter. Here's a tweet with video queued up to a powerful section in which the South African geographer Catherine Sutherland focused on the innovations over time that have boosted resilience in one particular urban settlement, Quarry Road West, built - like so many - in a river floodplain because no land is available for the poor elsewhere.

We discussed why an emissions-centered focus in climate policy can dangerously prolong the plight of the world's most vulnerable countries and communities. Saleemul Huq noted how the vast majority of flows of climate finance and development funding so far have gone to energy projects - not resilience work.

Slowing warming by cutting emissions of greenhouse gases is a prime imperative of our generation, as I've written since 1988. But that effort won't benefit anyone at risk today - or even through 2040 or later - because of the momentum in the climate system.

That's why it's essential to boost local adaptive capacity now. And the world is not remotely engaged on this, the panelists agreed.

In a tweet building off my Sustain What coverage, the geographer Saffron O'Neill said something a heap of disaster researchers agree with: “[N]o doubt climate change affects hazard. But if risk = hazard + exposure + vulnerability, we're forgetting key parts of the risk equation.”

~ ~ ~

Insert, May 20, 2022 -

One of my favorite scientists focused on this issue is Diana Liverman, who just retired after an extraordinary career as a climate-focused University of Arizona geographer and author on several Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessments.

With her training in geography, Liverman was always looking at more than changes in temperature, wind and precipitation, keenly aware that social conditions are the main shapers of climate impacts - particularly in communities pressed to the margins by poverty or prejudice.

In a Sustain What conversation during one of the West’s recent record “heat dome” events with Liverman and disaster-impact researcher Laurens Bouwer, Liverman offered a beautifully distilled way to clarify how to think about risk when both climate and societies are changing. Watch the whole hour here but here's the key moment:

"When we talk about climate risk, some people still just think it's the probability of the heat wave. But we need to think about risk not as the probability of the heat wave, but the probability of harm.

“Poverty is massively important in explaining vulnerability. We see in a lot of parts of the world, even though we've brought millions of people out of poverty, that there are parts of the world where aspects of poverty make people very vulnerable. The work we've done in Mexico and in other regions shows that if you're poor and they privatize the water, it makes you more vulnerable.

“If you're an indigenous community and somebody steals your land, you're vulnerable. There are so many ways in which addressing basic social welfare can reduce vulnerability, whether it's in New Orleans or Mexico City. And with the heat wave here, it's the poor who can't afford to pay for air conditioning, who can't afford to insulate their homes, and who are living on the streets or working in outdoor occupations and one hundred and fifteen degrees Fahrenheit.”

I'll continue to draw on Liverman's wisdom for years to come and hope you do, as well.'

~ ~ ~

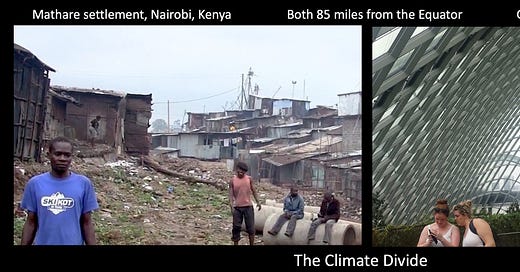

Here's a piece of art I pulled together to help make the point:

No matter what happens with CO2, climate risk will continue to rise as long as the devastating shove of entrenched disregard or prejudice continues to force tens of millions of poor or marginalized people into vulnerable floodplains or up steep, hazardous slopes even within today's otherwise-prosperous communities.

I'm very proud of the "Climate Divide" special report I wrote with a world-spanning batch of colleagues at The New York Times in 2007. But we looked country by country and missed the granular reality that vulnerability is community by community and shaped not by climate change, but by societal failures.

The resulting vulnerability emergency is something that can be attacked with rapid results. Bangladesh and the Netherlands - poor and rich - have demonstrated how to deeply cut losses from cyclones and floods.

I'll be adding more highlights here later from the lead author of the Nature flooding paper, Beth Tellman, who's moving from Columbia to the University of Arizona); Saleemul Huq from Bangladesh, Catherine Sutherland, who's an associate professor in development studies at South Africa's University of KwaZulu-Natal; Jean-Martin Bauer, senior digital advisor for the U.N. World Food Program and the organization's former country director for Republic of the Congo; and Simon Young, senior director at the global advisory company Willis Towers Watson.

Thanks for weighing below or on Facebook or Twitter.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here.