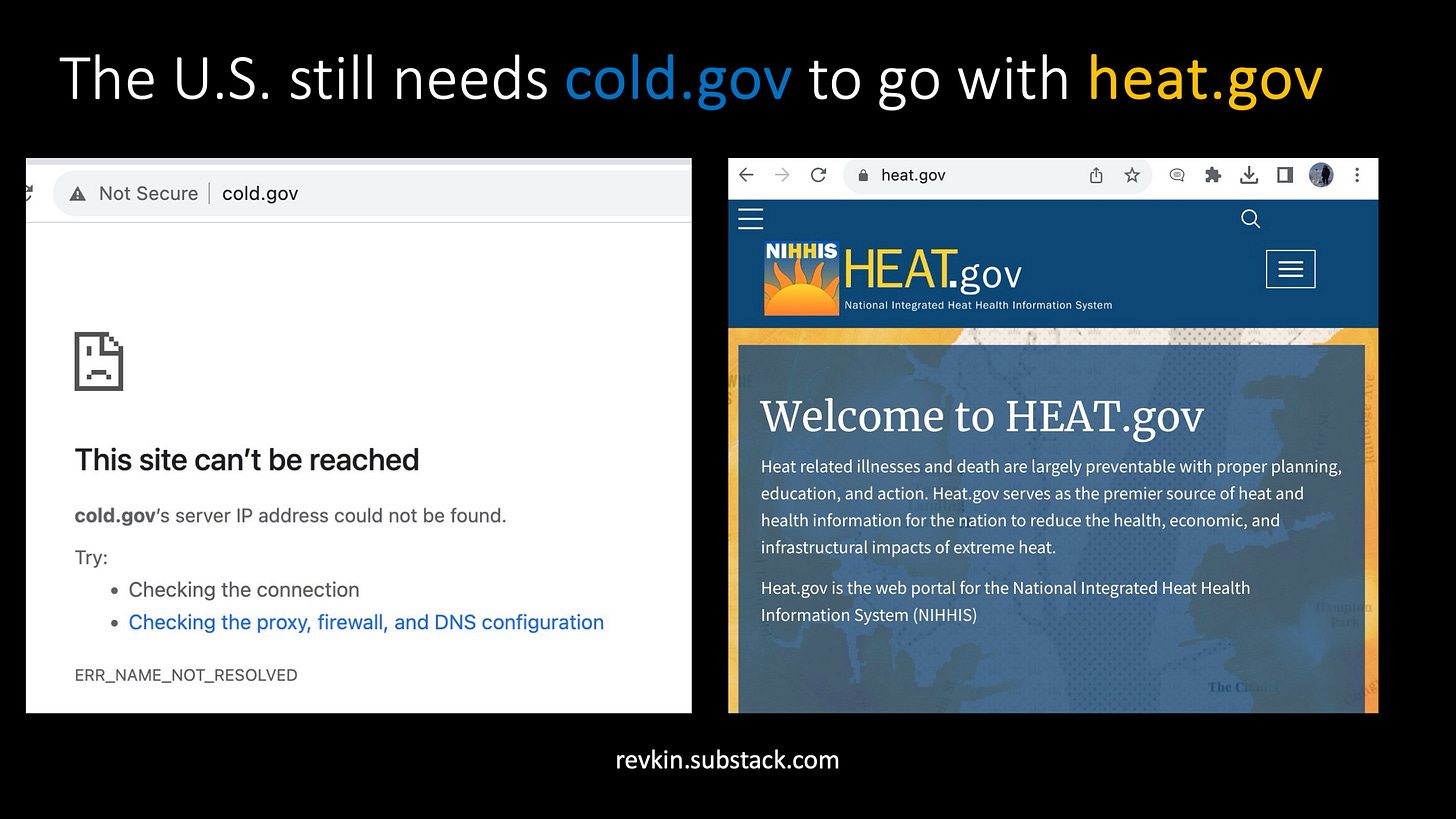

Heat.gov is Great, But Where's Cold.gov?

Even though more people die from heat than high-profile climate calamities like hurricanes and floods, this creeping killer gets too little attention. New online resources can help. Next up, Cold.gov?

This piece was first posted in the summer of 2022 before my shift from Bulletin to Substack, but - for obvious reasons - remains relevant whenenver and whereever people are at risk from extremes of heat and cold. Various updates are included.

It's great that the Biden administration took a solid step in 2022 toward building a more heat-resilient nation with the launch of Heat.gov - a website consolidating data and resources, old and new, aimed at boosting regional resilience to high temperatures on a human-heated planet.

As I've written from 1988 through through now, one of the most basic impacts of warming the global climate through a buildup of heat-trapping greenhouse gases is in amping up heat waves. Add to that how paving the urban portions of the planet creates "urban heat islands."

Add evidence showing how inequity or injustice shapes who is most vulnerable to heat. Think of the farm workers down the supply chain leading to your refrigerator. Ponder how past racism shapes which city blocks are currently hottest.

Finally, take into account what climate-health expert Kristie Ebi of the University of Washington has long noted: "Nobody needs to die in a heat wave" if communities are alert, prepared and responsive. (The World Health Organization agrees.)

Sum up these factors and you see why it's vital to improve monitoring, planning and response capacity. Heat.gov should help, particularly on the preparedness front. No community can complain it was caught unaware in the next head emergency.

Where’s cold.gov?

I still feel the nation needs a Cold.gov website, as well. There's long been expert debate about which extreme kills more Americans, with different agencies and independent researchers using different methods. But, as the weather maven Jeff Masters concluded in 2019, it's clear that both needlessly take hundreds of American lives each year. And while it's clear the risk of heat deaths is expanding in a human-heated world, it's worth noting that one 2015 study by Patrick Kinney and others found that "reductions in cold-related mortality under warming climate may be much smaller than some have assumed."

Insert, July 16, 2023 > I asked NOAA press folks a year ago why there isn’t a cold.gov and just got an answer last week. It’s appended at the bottom of this updated post.

Over on The Climate Brink, climate scientist Andrew Dessler has posted the first of a three parter on gauging losses and risks from heat and cold on a human-heated planet. I highly recommend you read the piece. Here’s one keystone point:

[F]or many cities in the mid-latitudes, …small amounts of warming will reduce temperature-related mortality while a lot of warming will increase it…. But there are some cities, typically in the tropics, where any warming at all will increase temperature-related mortality. < End insert

An all-hazards focus cutting climate risk

In a way, what's really needed everywhere is a core focus on reducing vulnerability to all extremes. Read this open-access 2018 study by researchers at the University of Michigan and Michigan Department of Health to see the value in building public health, housing and related strategies that work for both heat and cold:

Climate change and temperature extremes: A review of heat- and cold-related morbidity and mortality concerns of municipalities

"Extreme temperatures can increase morbidity and mortality in municipalities like Detroit that experience both extreme heat and prolonged cold seasons amidst large socioeconomic disparities. The similarities in physiologic and built-environment vulnerabilities to both hot and cold weather suggest prioritization of strategies that address both present-day cold and near-future heat concerns."

Don't be distracted by attribution debates

Despite headlines and spin, it's still tough to disentangle global warming and natural variability in long-term heat wave patterns in the United States. That might seem surprising but was a clear conclusion of both the last U.S. National Climate Assessment and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports.

I recommend you read the recent post on this by Roger A. Pielke, Jr., an expert on environmental and climate trends and policy at the University of Colorado, Boulder. I've long found him to be a vital resource even as others have attacked him when his findings don't align with their prescriptions for climate solutions. He includes these graphs from the National Climate Assessment:

Pielke explains:

"There are a few things that jump out from these figures. One is that heat waves of recent decades have not reached levels seen in the 1930s, either in their frequency or intensity. The NCA observed that the IPCC (AR5) concluded that “it is very likely that human influence has contributed to the observed changes in frequency and intensity of temperature extremes on the global scale since the mid-20th century.” But at the same time, the NCA also concluded, "In general, however, results for the contiguous United States are not as compelling as for global land areas, in part because detection of changes in U.S. regional temperature extremes is affected by extreme temperature in the 1930s."

To me, efforts to attribute some portion of an extreme event or long-term trend to global warming are important science but can distract from the key need - cutting vulnerability now to extreme events, with a focus on where the biggest and most dangerous gaps exist. (Yes, I've written this before and will do so again.)

The United States, through the spread of air conditioning and other changes, has been cutting human losses to extreme heat over the decades. But there's much, much more to be done.

In the news release on the website launch from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Cecilia Sorensen, director of the Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education at Columbia University, explained the gap between information and response this way:

“Currently, few health systems have heat action plans and heat exposure is rarely integrated into real-time clinical health decision-making for patients.... With more frequent, intense and longer lasting heat waves, there is an urgent need for increased health system preparedness to meet the growing burden of heat-related illness.

Heat.gov should help.

The website is a portal to information and tools that, like so much of the government's climate-related output, have for decades been inconveniently scattered across more than a dozen agencies. But much here is new, as well, including mapping tools allowing users to sift for real-time heat risk and vulnerability down to county and city scale.

From the Department of Health and Human Services, there's a monthly Climate and Health Outlook report with a section on heat, including a region-by-region look at the proportion of emergency room visits attributable to heat.

There are webinars to review, including this one describing how communities, through active citizen civic science, are taking heat readings to clarify where heat risk is greatest. Here's more on these urban heat island mapping campaigns from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

There are detailed sections with information on populations most at risk.

From Heat.gov - who around you is at greatest risk

President Joe Biden last week announced how existing funding will be directed to cut heat risk, along with steps by the Department of Labor to develop and enforce standards for workplaces. (Read the White House package.)

For resilience to extremes, bolster the "care economy"

What is less clear is how to make all of the heat data and analysis at heat.gov useful at the community end without a lot of new funding, training and career building. (The same would be true, obviously, for a cold.gov.)

America's public health system and emergency response capacity are already deeply strained by the pandemic and thousands of unfilled jobs. I asked about this in the online press briefing for the Heat.gov release.

"This is a big challenge," Patrick Breysse, the director of the National Center for Environmental Health, replied. "Public health support at the local and state level is not sufficient."

He cited a survey of local and state public health officials, saying, "87 percent responded that they don’t have the staff to deal with these issues going forward."

Once again, Congress has to step up, or recalcitrant lawmakers need to be voted out of the way.

Republican blockades seem idiotic given how many of the "care gaps" in the United States are in rural red regions. Read Nikeya Alfred's KHealth post[*] and Alexis Jones at Health.com.

In a Sustain What session back in early 2021, when the focus was vaccine distribution gaps, Irwin Redlener, a Columbia University pediatrician and public health advocate long focused on emergency response, described a critical data point that is as relevant in pondering climate resilience:

There's a federal web tool for finding Health Professional Shortage Areas.

For the record, I now see what this is like, having moved to rural coastal Maine.

Without fixing such gaps, all the websites in the world won't matter much.

More resources

The National Center for Healthy Housing has assembled cooling center information from all of the states.

Another great set of resources for cutting risk from extreme heat is being developed under the Extreme Heat Resilience Alliance of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center.

Make sure to explore the Heat Action Platform - described as a tool for city officials, practitioners and financial institutions to find guidance, resources and build custom tools and programs that can cut human and economic impacts of extreme heat at the regional or municipal level. Explore the platform here.

It is set up for local governments or other institutions to build heat-risk reduction into existing programs or investments or create bespoke projects with expert input.

But of course any citizen can use this tool to pull together data and ideas that can prod local elected officials or financial institutions, as well.

This "match.com" style destination reminds me of the American Geophysical Union's Thriving Earth Exchange, a hub where communities facing risks like flooding, landslides, erosion and the like can find relevant expertise.

As with the Thriving Earth Exchange, the key challenge with both Heat.gov and the Arsht-Rockefeller project is what I call the "scale monster."

Who facilitates the engagement with communities facing heat emergencies or other environmental challenges?

It's one thing to map a risk; it's another to have the dispersed array of trained practitioners able to build outreach and responsiveness, particularly in ways that reach people most at risk.

A heat wave may be widespread, but heat RISK is block by block, home by home - and strongly linked to poverty and past prejudice.

With both pandemic and climate resilience in mind, the challenge in ramping up public health capacity is global, as a new McKinsey & Co. report explores.

Read

Please read and share Rebecca Leber's powerful report in Vox revealing how poverty and outdated utility norms amplify heat risk for those most vulnerable.

Your turn

So dive into Heat.gov and the other resources here, then click back to my post on shaking out community climate vulnerability and let me know what you're doing to make a difference. Here's that story (just add heat to the mix with flood and storm):

A host of research projects at the Columbia Climate School have focused on heat trends and risk, including a recent study on the tripling of urban exposure to heat due to population shifts and climate change.

There's a fantastic related interactive map showing "Increasing Global Urban Population Exposure to Extreme Heat."

Send me feedback (including corrections!), tips, ideas here.

Find my social media accounts, books and music in a click here. And please share Sustain What with solution-focused friends and colleagues.

Correction

* I initially mixed up Khealth.com, a commercial healthcare site, with Kaiser Health. This says a lot about the muddled mix of paid content and news out there. Apologies.

NOAA’s answer

We appreciate that heat and cold are related issues and that as you write, “there is a need to reduce vulnerability to all weather extremes.” There also are related solutions offered by the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). We chose to focus on heat with Heat.gov because NWS Hazard Statistics indicate that it contributes to a larger share of the weather-related mortality and because reports such as the USGCRP Climate and Health Assessment indicate the net burden for temperature-related deaths will be on the heat side rather than the cold side on climate timescales.

Research also has shown that while once there was a one-to-one relationship in the U.S. between extreme heat and cold events, that has changed in recent decades to two-to-one for heat extremes relative to cold extremes. Research shows this gap will continue to widen due to climate change with heat extremes outpacing cold extremes. Here is research from this study from Meehl et al. 2009 on this.

The National Weather Service (NWS) currently provides safety information on cold and wind chill during our winter safety campaigns and has the following websites focused on cold and wind chill:

To alert the general public on dangerous cold conditions, the NWS issues Wind Chill Watches, Warnings, and Advisories. NWS continues to work on improving awareness and messaging of danger from cold and will be consolidating the wind chill alerts with Extreme Cold Warning, Extreme Cold Watch, and Cold Weather Advisory. The purpose is to enhance cold messaging regardless of wind factor. Thank you,

Monica Allen, Director of Public Affairs, NOAA Research