Almost a decade ago, I was approached by a publisher of illustrated histories of ideas and disciplines (The Law Book, The Physics Book, ….) to pull together an illustrated volume exploring 100 moments in humanity’s relationship with, and understanding of, weather and the climate system.

It was a lot of work, but illuminating and fascinating work - and took a little village. My wonderful wife, Lisa Mechaley, a longtime sustainability educator, joined in the research and writing. I also enlisted a batch of friends and scholars with particular experience or specialties to contribute some of the mini chapters.

The result, Weather: An Illustrated History, from Cloud Atlases to Climate Change, was reviewed favorably by many. I particularly enjoyed Jason Samenow’s description in a mini review and interview with me in the Washington Post: “Think of this book like dining on tapas, boasting savory flavors, some unexpected, that constitute a satisfying whole..”

I really do see the book just that way - as drawing people of all ages into the deeper story of humany’s ever-evolving relationship with the elements.

There’s still time to buy and receive the book before Christmas and Hannukah (at least via Amazon), and I hope you’ll consider doing so!

Here’s an excerpt from my conversation with Ira Flatow on Science Friday to get you started

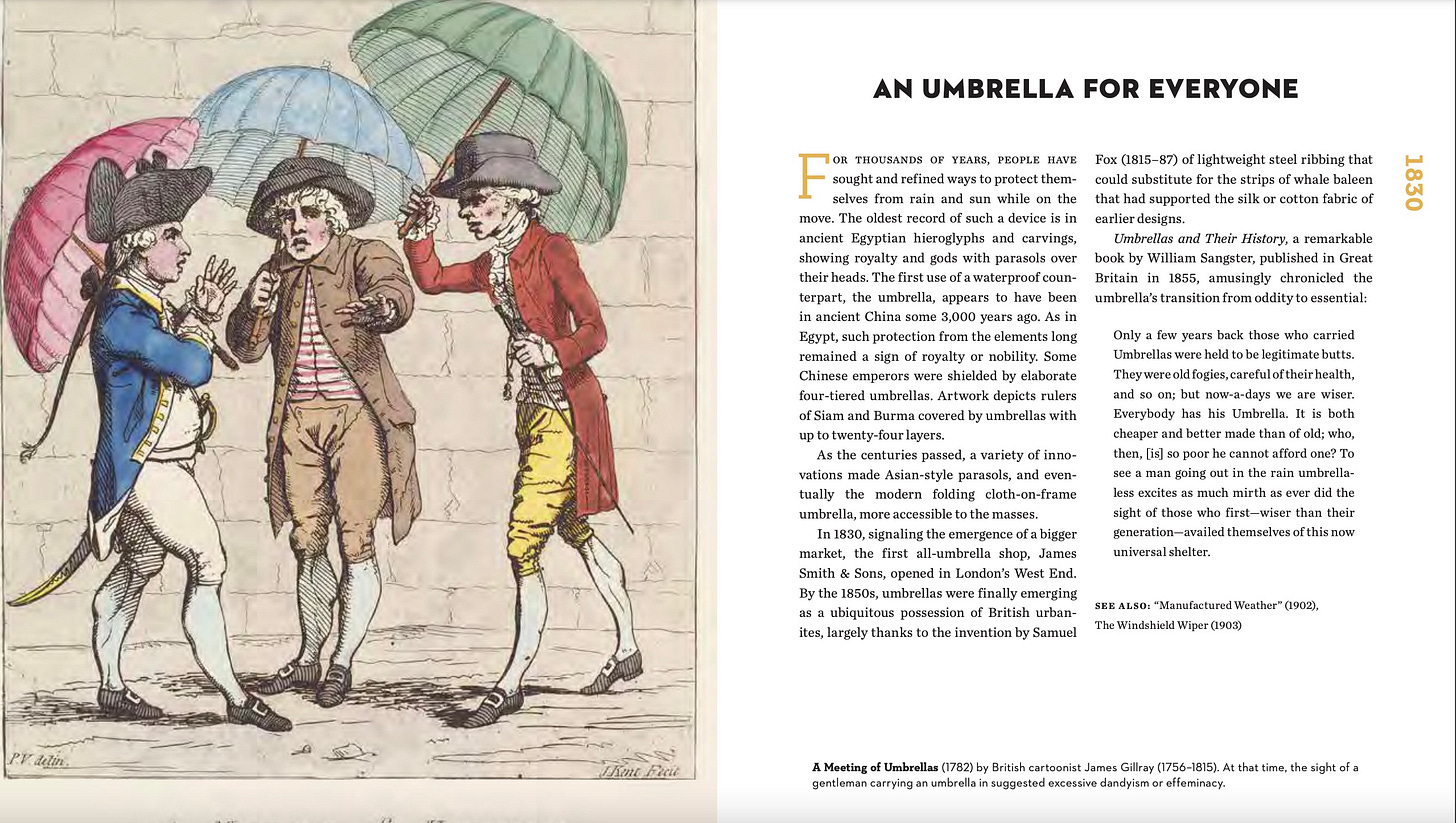

Here’s one spread on the history of air conditioning, which was marketed as “manufactured weather” in the early 20th century (way before discussions of geoengineering - essentially a manufactured climate; that’s in the book, as well, of course).

Here’s a video in which I explain the book project:

Here’s some of the Q&A Jason Samenow did with me for the Post, along with some spreads from the book.

Jason - Who is its intended audience?

Andy - It may sound pat, but this book was literally written for everybody — in the sense that it’s descriptive, not prescriptive. The chronology shows how research and observations pointing to human-driven global warming are an inherent part of the broader sweep of science illuminating the nature of Earth’s climate system — including the parts that remain unknown and some even unknowable.

It was designed for everybody in another way — with art accompanying every milestone and clarity guaranteed by my co-author, Lisa Mechaley, a longtime middle school science teacher who now helps other busy teachers incorporate environmental insights into lesson plans (and who happens to be my wife!).

Jason - In researching all of these fascinating vignettes about our evolving understanding of weather and climate throughout history, what one thing surprised you the most?

Andy - I was most surprised, after more than three decades of reporting on climate and weather, by how much I didn’t know — that the worst wildfire in U.S. history wasn’t in the West, that so many amateur scientists played vital roles in knowledge building, that a woman first documented carbon dioxide’s potential to warm the planet and another invented the windshield wiper, that the jet stream was weaponized in World War II.

Jason - You write a lot about some of the most important people who made critical, groundbreaking discoveries about weather and climate. Is there someone who, in your mind, stands out as being vastly underappreciated for his or her discoveries?

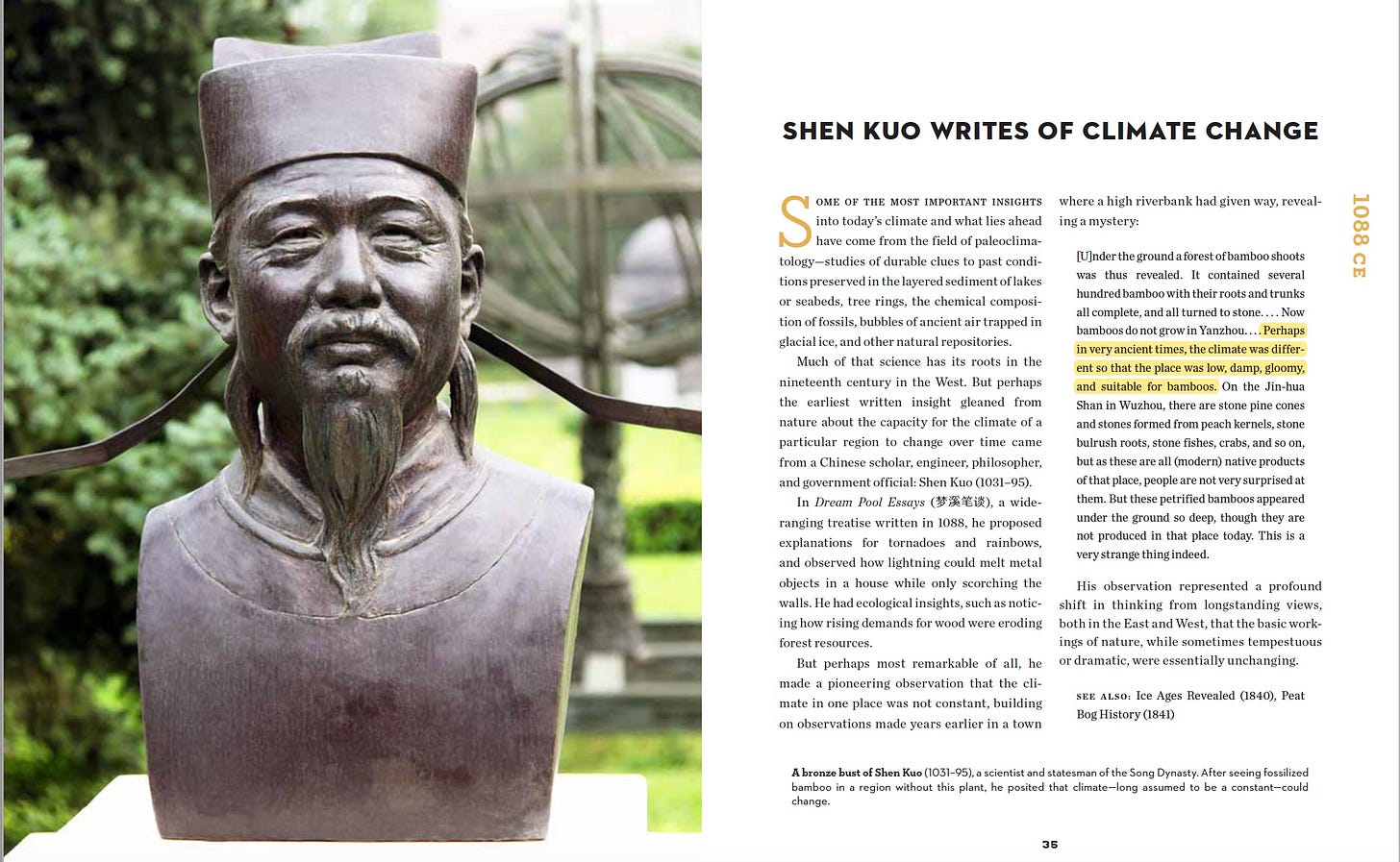

Andy - I loved stumbling on a pioneering insight about the potential for climate to change written by an observant Chinese polymath and government official, Shen Kuo, in 1088 — after he’d seen fossil bamboo in a region with no bamboo.

Hitler’s disastrous disdain for meteorologists

Jason - What is your favorite, single most memorable vignette in this book effort?

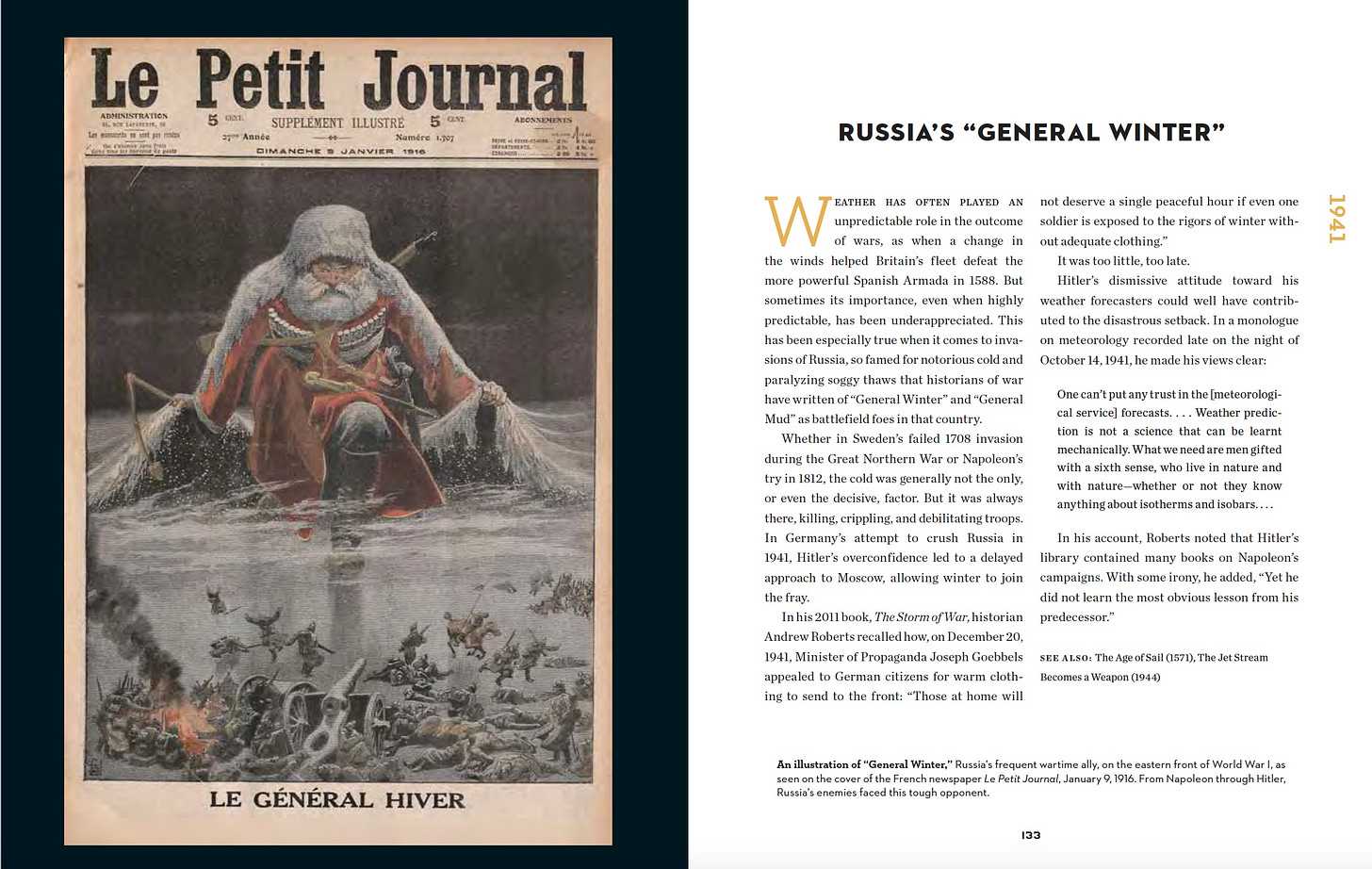

Andy - As you can imagine, this is an excruciating question, given the range of events and insights we discovered. So I’ll offer one that has both memorable artwork and an extraordinary look at Hitler’s dim view of meteorologists — a stance that did not serve him well on the Russian front:

Weather has often played an unpredictable role in the outcome of wars, as when a change in the winds helped Britain’s fleet defeat the more powerful Spanish Armada in 1588. But sometimes its importance, even when highly predictable, has been underappreciated. This has been especially true when it comes to invasions of Russia, so famed for notorious cold and paralyzing soggy thaws that historians of war have written of “General Winter” and “General Mud” as battlefield foes in that country. Whether in Sweden’s failed 1708 invasion during the Great Northern War or Napoleon’s try in 1812, the cold was generally not the only, or even the decisive, factor. But it was always there, killing, crippling, and debilitating troops.

In Germany’s attempt to crush Russia in 1941, Hitler’s overconfidence led to a delayed approach to Moscow, allowing winter to join the fray. In his 2011 book, The Storm of War, historian Andrew Roberts recalled how, on December 20, 1941, Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels appealed to German citizens for warm clothing to send to the front: “Those at home will not deserve a single peaceful hour if even one soldier is exposed to the rigors of winter without adequate clothing.”

It was too little, too late.

Hitler’s dismissive attitude toward his weather forecasters could well have contributed to the disastrous setback. In a monologue on meteorology recorded late on the night of October 14, 1941, he made his views clear:

“One can’t put any trust in the [meteorological service] forecasts. . . . Weather prediction is not a science that can be learnt mechanically. What we need are men gifted with a sixth sense, who live in nature and with nature — whether or not they know anything about isotherms and isobars. . . .”

In his account, Roberts noted that Hitler’s library contained many books on Napoleon’s campaigns. With some irony, he added, “Yet he did not learn the most obvious lesson from his predecessor.”

It looks as an amazing and unique book. Looking forward we can have it in Spanish bookstores soon (I’m notas an Amazon friend!).

Andy does and did so much good reporting for us on this heating planet! Thank you, Andy!