All Hail Elon Musk - the Greatest Spur to Social Media Innovation Ever?

In the long run, Musk's Twitter takeover may be seen as serving as an overdue stimulus for innovation in pursuit of sustainable, open, civil online discourse.

Let’s step back for a second from all the second guessing, hair-on-fire reactions and stampeding for the exits to assess what’s really going on amid the rogue waves generated as Elon Musk’s takeover continues to roil Twitter (the platform and the company).

Musk’s abrupt moves at Twitter are arguably the best thing that ever happened to social media, given the resulting ferment.

All around the online world, mad scrambles are under way to improve or cobble alternatives. It’s way too soon to know what will emerge, but this could be one of those moments where a dominating enterprise goes a step too far, stimulating innovation elsewhere and eventually dissipating into irrelevance.

Or it could result in a better Twitter if those using it find ways to make it useful with or without Musk’s moves.

Tell me this statement doesn’t resonate with what’s happening?

The fundamental creativity of humans is on vast, chaotic display. Stuff is just coming out all over. I mean, I have to say, as an evolutionary biologist, I think that patterning of how communication technologies arise and then get co-opted and then get tied up by commercial or corporate interests or governments, the part that doesn't get said maybe or is sort of in the background, is that as soon as that happens, people begin looking for a different way. And eventually they create something else. There's always something new in order to achieve that thing that people want, which is the freedom to create their own way of interacting with one another.

In a moment you’ll learn who said it - in 2013!

As I’ve written, I’m not abandoning ship yet. Twitter remains far bigger than Musk. Enormous value can be gleaned with or without blue checks (my post on eight ways). A tweet from @elonmusk today makes the point that improvement is needed.

The open question is how much improvement, or degradation, will be shaped by Musk at Twitter, how much improvement can be driven by Twitter users through altered practices, and how much any alternative digital public square can improve.

I don’t see the latter happening any time soon, so working with the Twitter we have, while energetically testing other options, is the path I choose.

Beyond Twitter?

Insert, 11/3, 5 pm ET - In a vital column for Time, Evan Greer (@evan_greer), founder of the digital rights group Fight for the Future, articulated the urgent challenge, and opportunity, that Musk’s Twitter takeover spotlights:

The truth is that we will never have meaningful free speech or human rights as long as we’re all digitally landless, paying rent in dollars or data. If we want a modern town square we can leave to our children and our children’s children, we need to build online spaces that can’t be owned or controlled by a single person, with tools to address harm, harassment, and injustice that give individuals and communities power over our own online experience.

Insert 11/4, 3 pm ET - I’ll be doing a Sustain What webcast soon with Greer and others on the ferment that is boiling in pursuit of alternatives as Musk’s Twitter moves play out. One exciting project, Project Mushroom, is hubbed at Currently, the weather and climate information service launched by Eric Holthaus (@ericholthaus). Here’s his Twitter thread with the basics. I just signed up and will report back soon.

Insert 11/9 - Greer offers a great low-confusion guide to getting onto Mastodon:

Lessons from 2013

That 2013 statement above was made during a fantastic conversation I hosted in 2011 while teaching my graduate course Blogging a Better Planet at Pace University.

The subject was Twitter and social networks. Our guests were Chris Messina (@chrismessina), the inventor of the hashtag (and many other things), Margaret Rubega (@profrubega), an evolutionary biologist at the University of Connecticut who was an early adopter of Twitter as a learning tool (I wrote about her repeatedly on Dot Earth), and David Weinberger (@dweinberger), the Harvard-based Internet analyst whose 2011 book “Too Big to Know” so excited me. Why? His call to action directly paralleled what I’d been trying to do with my Dot Earth blog:

Our task is to learn how to build smart rooms—that is, how to build networks that make us smarter, especially since, when done badly, networks can make us distressingly stupider.

When time, watch Weinberger’s 2012 Google book talk.

But first absolutely watch my discussion with this trio (an early Google Hangout). I’m adding the slightly cleaned-up transcript below. It was Rubega who made the hopeful point I quoted above.

Talking Twitter and the Web with Messina, Weinberger and Rubega

Andy Revkin - I'm going to go to Chris Messina. I was just extolling the virtues of your past experience when you were at Mozilla. It was 2007 when you said, Hey, why don't we use the pound sign as an organizing widget? You really you really did invent this?

Chris Messina - Yep, that happened. I know it's really weird.

Andy Revkin - Can you just sort of explain what you see as the value of having a hashtag as opposed to just a general search term?

Chris Messina - Yeah, actually, it's different than just being about search. I should point out that when I when I came out to Silicon Valley in 2004 or whatever, and I started working for Mozilla as a community organizer, it was really important to me that there be a competitive ecosystem for applications, whether they're social applications or the sort of like generative applications that allow other people to build on them. And I quickly sort of parlayed the work that I've been doing on an open-source browser into work on the social web. In 2007, what was kind of happening, people were starting to have this dual experience between the desktop experience with big computers and keyboards and stuff like that and their phones.

What Twitter did at that time was it took a private channel like SMS and turn it into a public channel. So it didn't really require people to learn something new. They could use an existing tool to then broadcast more broadly. And the problem with that, though, is that that's sort of a shotgun approach to creating meaning. And so you hit all these people with like buckshot that just aren't interested in the stuff that you have to talk about. It's not just about like your breakfast cereal, it's about the things that you find interesting or the context that is relevant to you and to perhaps the people around you.

And so you want to find a way of giving people like a token to identify the meaning that you're actually kind of trying to talk about. Search is obviously one way to do it. But the reason why the hashtag was useful and valuable and interesting was because you can kind of put it out there in space like we used to do in IRC and immediately people can go into that conversation or context and start sharing new information, or look at information that had already been shared about it.

AR - RC, Internet Relay Chat, is a text-based chat system for instant messaging.

And so that was that was something that was important about the design of the hashtag. In addition, there was a number of calls for creating traditional-style groups - message boards, forums, mailing-list type groups that you could go into and that were controlled and that you could kick members out and add members in and so on and so forth. And I just didn't want that kind of overhead when I was on my phone.

And of course, in 2007, I probably still had a Nokia with an actual hardware-driven keyboard as opposed to a touch keyboard. So all of those things factored in and it allowed for the creation of this very simple, very stupid convention that ultimately could go anywhere that text could go.

That's why it's not, in my mind, just about search, but it's also about thinking about that cross-domain, cross-medium, cross-channel unification that doesn't require people to learn a whole lot of new stuff to take advantage of it. It's a transparent design that when you see it basically know how to use it. You can do it even if you don't get it and then eventually you're participating anyways.

AR reflection - This is why, at the moment, I don’t see Mastodon or the like catching fire. They are clunky and not intuitive - so far.

Andy Revkin - So I'm going to switch for a second over to Margaret Rubega, who is in education and certainly a masterful user of the hashtag [in a University of Connecticut course she teaches on birds].

Margaret Rubega - It gets taught every spring semester. It's an ornithology course, which for the uninitiated means a course about birds. And it's an unusual natural history type course in that usually those courses are quite small and this course has grown very large. Sometimes I'll have as many as 100 students in a giant lecture hall. So traditionally you would teach that kind of a course by taking people outside. But this is a lecture only, and I really wanted to get the students to get a sense of the way in which what we were talking about in class actually was not just a BBC phenomenon that you watched on your TV, that if you walked outside and looked around, you would see what we were talking about in class. Twitter just struck me as a really great tool to kind of sum. Their own attention to their phones, to something that I really wanted them to pay attention to. I just gave them an assignment that they needed to post to Twitter. It's that assignment is now structured so that they have to do it about once a week throughout the semester, a minimum of once a week throughout the semester. They're supposed to go outside of class, post to Twitter where they are, what they're seeing in the bird life around them, and somehow connected to course content.

Andy Revkin - And you use the hashtag #birdclass, right?

Margaret Rubega - That's right. And it has been adopted or co-opted, or whatever you want to call it, by a wide variety of people who are not actually in my class. People who are interested in birds will throw things up at the #birdclass hashtag. It has to be admitted, there's a subculture of students at universities across the country who now use the hashtag to indicate a gut course for which they will not do any work.

Andy Revkin - Oh, funny.

Margaret Rubega - They're "birding" class. So it's #birdclass.

AR reflection: These parallel uses of the hashtag reflect the open, iterative nature of all these innovations.

Andy Revkin - But I have seen people who are birders or bird enthusiasts who also kind of respond or retweet stuff that you guys put out there. I certainly do.

Margaret Rubega - Yeah, absolutely. And interestingly, it's been interesting to me to watch the tail of students who started the assignment in a, shall we say, skeptical frame of mind who are still tweeting a year or two after they've graduated and left, the university will still climb on and go "saw this really great duck today" and put the class hashtag on it. So it's as an assignment it was just a one-off. I thought, well, it seems like it might be a useful tool. We'll give it a whack. And it succeeded way beyond my wildest dreams. They use it in ways that I really did not anticipate.

AR reflection – Again, adaptability, innovation, experimentation.

Andy Revkin - Do you do you recall where you first saw a use of Twitter that made you think that this would be something to do? What were you seeing that said, hey, I should do this with my students?

Margaret Rubega - I was seeing nothing that gave me that particular idea. What I was seeing was a lot of people bashing the whole idea of Twitter, right? 140 characters. You're never going to see anything except people posting about what they had for lunch. And I thought, well, okay, 140 characters, but haiku is a tight form, too. It's not intrinsically necessary that it be trivial or badly composed. And really, my use of the thing was driven by - I just somehow wanted a way to make them look up when they were outside. The phones were in their hands. You know, if you're teaching a college class now, I'm sure you're aware you're competing with the devices.

Andy Revkin - Yeah, that's been one thing in my blogging course. I've figured go with the flow instead of trying to fight it seems to be a better approach.

Margaret Rubega - I felt like Twitter gave me a really useful tool to subvert that attention to their devices. I wasn't asking them to write me a lengthy essay every week. They were out and about with their phones. They could post to Twitter from their phones. They're on their phones a lot of the time. Just look up and then use the phone that you have in your hand to connect back to class one.

Andy Revkin - One last question before I switch to David Weinberger. Has this evolved to taking pictures, too or not?

Margaret Rubega - It's gone beyond mere taking pictures. Students have invented all kinds of uses for it that I really did not anticipate. I've had students engage in something that we've learned to call a Tweet ID whereby they go out and if they see a bird they can't identify, they get on Twitter and tweet to me, you know, "Need a tweet ID" and then just describe the bird or post a picture. And then I tell them what it is. But it's been the ability over the course of the semester to boil down to a description of the really salient details of what the bird looks like. You only got 140 characters. You cannot you can't include extranea. It makes them really think about what actually matters.

AR reflection – This was before iNaturalist and a suite of bird song and identification apps emerged.

Andy Revkin - So. All right. David, The idea that students are inventing other ways of using it seems to fulfill what [you’ve been] describing as the potential of this kind of technology.

David Weinberger - What Margaret is talking about just makes me so happy. Twitter is actually almost the perfect example because it is [so] minimal…. 140 characters. Initially no images, no metadata attached to it. That is no information about the information that the user could supply, which is something that Chris took care of with the hashtag.

So here you have the very paradigm of a minimal form of communication. It's like a telegram, you know. You can't get it much briefer than that. It's put out into the wild, into a a net where lots of people can use it and they can invent stuff. They can invent their own coded language. A hashtag now takes on a new meaning that indicates that what follows is what the piece is about, so that now information can cluster and then people can cluster around the hashtags.

So you end up with completely unexpected things, whether it's people posting pictures of birds so that this network of knowledge can identify it or it's Andy Carvin during the Arab Spring was doing this sort of heroic journalism that nobody ever would have expected, which turned Twitter into, I think without a doubt, the single best source, not only for real-time information about rapidly breaking news, but for information that was coming more directly from the people who were involved in it than any other form of journalism basically ever enabled.

See: Sourcing the Arab Spring: A Case Study of Andy Carvin's Sources on Twitter during the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions - Alfred Hermida, Seth C. Lewis, Rodrigo Zamith (Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 2014)

So here's a flourishing in realm after realm, from birds to street revolution, that all emerged from the most minimal form of human communication that one could imagine - 140 characters....

This is the type of flourishing that you get with a technology that is so open that we fill it with human invention and human need and human care. And with the power of what happens when you have lots of little pieces join together.

So just to wrap up what I'm saying, in one sense, it's the story of the power of sociality. It's a story of the power of metadata, even just a little bit of metadata. And suddenly you get you get empires of meaning forming. And it's a story as well of the amazing power of incremental change - that is lots little tiny pieces that get joined together, of iteration, that takes very short messages from on the ground and turns them into a comprehensive story about a revolution. It's really an amazing story of flourishing.

Andy Revkin - So maybe Chris should have a Nobel Peace Prize in his future. Just kidding. I want to talk about commerce.... There’s a young woman here working in a health field related to breastfeeding and trying to get established as a communicator looking at how you make a living doing this kind of thing.

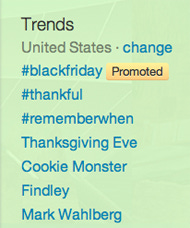

The flip side of the monetization thing is I remember the first time I saw a “promoted trend” on Twitter. Boy, did that piss me off. I wrote a piece for Dot Earth on the whole idea of a promoted trend. What does that mean? It's just it's beyond “1984.”

Margaret Rubega - Is it really distinct from what marketers have done throughout the history of the world? They're always subverting the language. This is one of the things that I find striking about the way people talk about these new tools. I agree that in a lot of ways they're revolutionary, but. the sort of things that people say are the sort of things that people always say about new tools. They're going to ruin the world, they're going to rot your brain, you know.

Andy Revkin - So, Chris, what do you think about this now?

Chris Messina - On the question of monetization and the question of doing this for a living, one, I think it's actually very hard to do social media well and do it for a living. It's like artists, as I've been finding. There's a lot of commercial jobs available for you to create great stuff for somebody else. But it's very hard to pursue your passions and then, you know, get paid for it unless you become sort of a breakaway hit and you've either got some great technology or you time it really well, or you just are so obsessive about it that you cannot possibly do anything else and you would probably give up eating or breathing in order to do this sort of thing.

For example, this guy, Trey Ratcliff, he's very active on Google Plus [AR - Remember Google Plus?]. He's got a bajillion and a half followers on every social network that he's on. He's not even, like, sponsored by like JCPenney or like whatever all these kids are doing these days. Instead, he just posts all these great HDR photos and sort of has led this revolution of making your photos look really bursty always. So he's just built up his following by creating a lot more value for all the people that follow him, rather than trying to figure out how to make money from it.

AR - This is what Trey’s up to these days:

Chris Messina - And so you kind of have to take the longer term approach, build up your reputation, become a bridge and an amplifier for other people. And I think that's more likely how you might find at least some success. In other words, I started out in 2004, 2005 trying to get everybody else around me to be successful. It wasn't really about me being successful. I wasn't motivated by money. I'm still not motivated by money. I'm interested in creating interesting things that help other people make more meaning in the world. As I've watched certain friends go off and become millionaires and stuff like that, I am more satisfied by creating things that other people are building upon different platforms that are more accessible and don't require me to create some enormous institution to support these things.

In other words, the technologies and the innovations that I've been a part of don't require you to get permission from me to use them. And that's been extremely awesome about the power of the Web and the power of the social web, and that's how I got my start. And so that's how I want other people to get their start.

Andy Revkin - David, you know, one of the big issues here in the end is, the whole system is sort of seen as free. And some of the values, like the value of spreading proper breastfeeding information in poor communities, are never going to be something that someone will probably pay for. I don't know whether any of you three see some way that those externalized values are sort of internalized. Is that possible? These are not restricted to the Internet.

The “primordial goop phase of the Internet”

Chris Messina - This is not going to be a useful answer. But I have been thinking about this stuff. And I think the reality is that we are in the primordial-goop phase of the Internet and all these technologies.

There's going to have to be an incredible shift in the way that we think about economics, the way that we think about work, the way that we do work and perform work, the way that we make opportunities available for people to pursue things that they're actually into and interested in, as well as what happens when we have many more robots living among us, when we have self-driving cars. A lot of things are going to be very, very different. If not in the next five years, easily the next 10 to 15 years. And it's going to cause a big shake up in the way that we allocate resources.

I don't know that we're going in the right direction right now, in which case we may end up in a very painful period of trying to figure out what we're supposed to do with this stuff. But hopefully the power of the internet is not tampered down by all of these crazy ass IPO's and people building advertising platforms on top of that.

The great thing about the web is its resilience and its ability to give newcomers new power that they didn't have before. And so I'm hoping that we're able to preserve that in whatever happens next so that we can actually deal with bringing about sort of a better future faster.

Andy Revkin - David, I wrote a piece not long ago comparing the development of the teenage brain to the development of the Internet right now. There was a cover story in National Geographic by David Dobbs, a friend of mine, on the amazing changes that take place in the brain going from teenage to adulthood. Parts of it kind of deconstruct and then reconstruct. All these neurons, connections are made and unmade within it. And when I look around at the noise on the Internet and the noise in our communication realm right now, it feels the same way. And are we in the primordial goop as as Chris said and just not realizing it. This is so nascent that it still hasn't really even taken form yet?

David Weinberger - I don't know. There's a couple of things that can happen and I don't know what's going to happen.

So the Internet could get closed off and become a set of apps, and apps running within environments that normal humans can't affect. I mean, most of us can't build an app. All we can do is consume them. And so and there's great convenience to that. And that may be the model. That may be the model that wins. That certainly will happen. We've seen this already. There will be applications that sort of get packaged up and appear to the consumer, to the user as simply things that exist in the world. And the fact that it's running on top of the Internet will be completely uninteresting to the user and the phone system. That's already the case. Users don't know generally that it's running on top of the Internet, and that's fine. That's fine with me, you know, not that I get a say in it. So long as the soup remains - as long as sure you can download apps, you can you can go into a walled garden for some of your time - so long as there is still a soup that anybody with an idea can use to create a new service, a new tool, a new app, a new page, a new network of people thinking together, a new Twitter. As long as that soup is there and open and available to everyone equally, then we will have perpetual innovation. And the innovation is not simply new technology, but it's new ways for us to connect with one another, to be with one another. It's perfectly possible that we'll lose that, either for economic reasons and/or for policy reasons that have been driven for economic reasons. That's why a lot of us are concerned about trying to preserve the open Internet and trying to keep a capture of it from the providers of the Internet - your AT&Ts and Comcast and so forth, from not only acting as if they are the Internet (they're not; they're providers of access to it) but actually legally becoming the only way you can get to the soup, in which case the soup disappears and all you get is the easy-to-consume content and apps. So it's really important that we try to keep the goop the goop and the soup the soup. That's where all the goodness comes from.

Andy Revkin - I love that idea. And do you think that Americans are remotely aware of that risk? Has there been any counterpart to that in other technological transformations where the country essentially was not realizing something that momentous was poised to happen?

David Weinberger - Well, Tim Wu has a really good book ["The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires"]. It's a wonderful history of communications in the 20th century, basically. And he looks at each of the industries - radio, television, telephone, telegraph - and shows that the same pattern happens, which is that there's an initial burst of enthusiasm. This is going to change the world. (This is sort of the other side of what Margaret said, that we also say it's going to destroy our children and rot their brains.) The initial burst of enthusiasm, the technology starts out as bottom up. Everybody can participate. It's ham radio. And then it gets consolidated by corporate interests and the soup gets closed off. Tim Wu has some hope as to why that the Internet is different, because there hasn't been such a soupy soup in technology since writing. That is a medium that connects us, that can be used for anything from Twitter to social networks to voting as a mechanism for telephony. Its plasticity is unmatched. And so there's some hope that maybe the Internet will be different. There's some hope that you can see the younger generations embrace of the culture of the Internet as a culture of openness. And there's tremendous I have tremendous fear that corporate interests are so overwhelming that it won't matter. It'll just go away. It will become like the telephone.

Andy Revkin - Margaret, from your vantage point, what's your sense of how this will play out?

Margaret Rubega - Well, I certainly don't have any more of a crystal ball than anybody else here. I absolutely agree that we are in this soupy, soupy Wild West part in which, man, anything goes. And the fundamental creativity of humans is on vast, chaotic display. Stuff is just coming out all over. I mean, I have to say, as an evolutionary biologist, I think that patterning of how communication technologies arise and then get co-opted and then get tied up by commercial or corporate interests or governments, the part that doesn't get said maybe or is sort of in the background, is that as soon as that happens, people begin looking for a different way. And eventually they create something else.

There's always something new in order to achieve that thing that people want, which is the freedom to create their own way of interacting with one another.

And, you know, I am the biggest Internet skeptic you invited in here tonight. Let me tell this story just to give anybody young who's there to appreciate what it is we're talking about. The day I started graduate school, and I'm old but I'm not that old, I walked in and sat down in my adviser's office and he said to me, hang on just a minute while I take this manuscript down the hall to the secretary. And he picked up his yellow lined paper on which he had handwritten in longhand his most recent paper, and carried it down to the secretary so that she could type it up on a typewriter to mail to the journal he was hoping to publish it in.

Andy Revkin - Yep.

Margaret Rubega - That's just in my professional lifetime. Not just my lifetime. My professional lifetime. The magnitude of change in our lifetime is just breathtaking. It would be okay with me if the tools stabilized for a while so I could stop learning new ones and just use them to maybe make some stuff for a while. And I think that's where some of the skepticism [comes from] - the oh my God, it's ruining the world, people's brains are rotting. People do get tired of having to keep up with change. But I have complete faith in the capacity of humans to keep inventing new stuff. So if the Internet gets co-opted, just imagine what's coming after that. I don't know. But it will be even more breathtaking than this, I suppose.

I have complete faith in the capacity of humans to keep inventing new stuff. So if the Internet gets co-opted, just imagine what's coming after that. I don't know. But it will be even more breathtaking than this, I suppose. - Margaret Rubega

Resources

Even if I weren’t now writing at Substack, I’d still point you to co-founder Hamish McKenzie’s dispatch on plans to shape what happens here in ways that could obviate the need for Twitter. There’s much more brewing out there of course. Post a comment with links to what you’re seeing.

David Weinberger posted on the Twitter conundrum a few days ago, using the past tense to indicate his enthusiasm for the platform:

Why I liked Twitter

I’ve been on Twitter for a long time. A very long time. In fact, I was introduced to it as a way for a bunch of friends to let one another know what bar they were about to go to. It seems to have strayed from that vision a bit.

I have not yet decided to leave it, although I’m starting to check in at Mastodon. Here’s what I use it for, in no particular order, and not without embarrassment:

Quick check on breaking news. It’s by no means comprehensive, and what trends is by no means always important. But I find some of it worth a click even as a distraction.

Quick commentary on issues of the day by people I follow because they’re good at that.

Issues worth knowing about raised by strangers who know about them.

Keeping up with fields I’m interested in by following people who I don’t know, as well as some I do.

Engaging with people I otherwise wouldn’t have kept up with.

There are people I know just barely in real life who I feel quite close to after many years on Twitter together.

Engaging with a low bar of social inhibition/anxiety with people I don’t know, sometimes leading to friendships.

An outlet for my stray thoughts and, well, jokes.

A medium by which I can publicize stuff I write.

A number I can cite to publishers as if people automatically read the stuff of mine I’m publicizing on Twitter.

The Twitter I’m on is often very funny.

Switching social platforms is hard.

Here’s Tim Wu on The Rise and Fall of Information Empires:

Help Sustain Sustain What

I hope you’ll help support my Sustain What project either by becoming a financial supporter or sharing this post with friends and colleagues.

Parting shot

The last few weeks have been a busy time of harvest here in downeast Maine - both at sea and on land. What’s happening on the landscapes around you?