A "Watchwords" Warning About Tipping Points Claims - Climatic and Societal

Meet authors of a new paper warning against widspread efforts to apply the phrase tipping points when describing physical climate hazards and societal responses (without some more research).

Read on to hear from a batch of the scientists and scholars who collaborated across many disciplines to write this new Nature Climate Change paper warning against overuse of the tipping point frame in describing both human-driven global warming and societal responses to this threat:

‘Tipping points’ confuse and can distract from urgent climate action

Robert E. Kopp, Elisabeth A. Gilmore, Rachael L. Shwom, Helen Adams, Carolina Adler, Michael Oppenheimer, Anand Patwardhan, Chris Russill, Daniela N. Schmidt & Richard York

I’ve highlighted the names of the authors you’ll meet.

You can watch and share the conversation on LinkedIn, YouTube, Facebook or via my X/Twitter account.

Watchwords is my running series on terms that confuse or distort, either unwittingly or intentionally, in pursuit of climate and wider sustainability goals.

Tipping points language has steadily built around humanity’s climate change challenge for a couple of decades. There’s now an international science collaborative, the Global Tipping Points project led by Tim Lenton at the University of Exeter.

(Here’s an interview I did recently with Lenton on humanity’s shrinking niche.)

And yet big concerns about this approach to understanding and addressing global warming are being expressed researchers across a range of fields, as this new paper summarizes in its abstract:

Tipping points have gained substantial traction in climate change discourses. Here we critique the ‘tipping point’ framing for oversimplifying the diverse dynamics of complex natural and human systems and for conveying urgency without fostering a meaningful basis for climate action. Multiple social scientific frameworks suggest that the deep uncertainty and perceived abstractness of climate tipping points render them ineffective for triggering action and setting governance goals. The framing also promotes confusion between temperature-based policy benchmarks and properties of the climate system. In both natural and human systems, we advocate for clearer, more specific language to describe the phenomena labelled as tipping points and for critical evaluation of whether, how and why different framings can support scientific understanding and climate risk management.

This divide is not new. See my 2009 New York Times article at the bottom of the post.

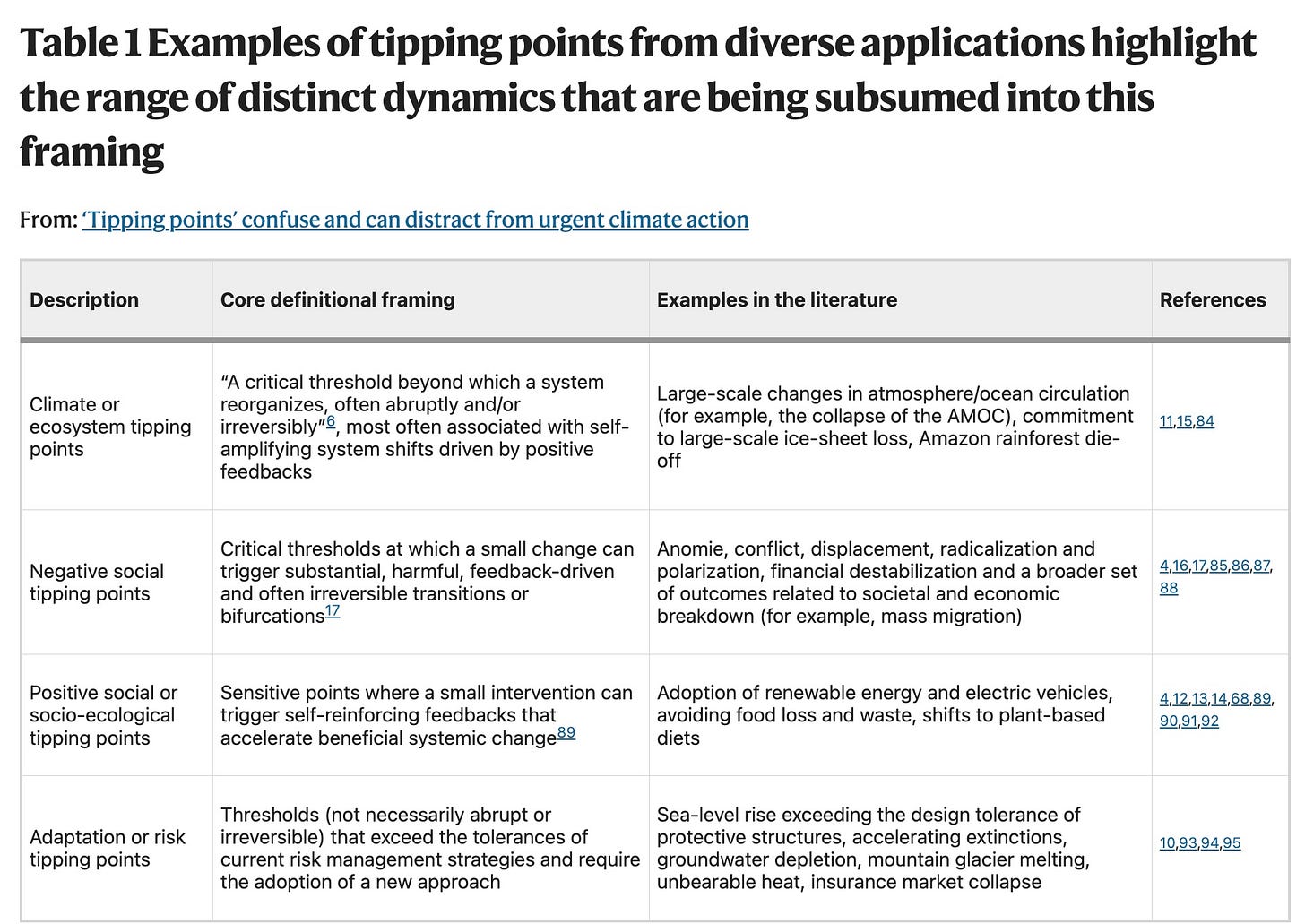

One concern of these authors: A murky mess of different dynamics are being distilled under a single label. Here’s a table from the paper.

The paper is behind a paywall, but lead author Bob Kopp of Rutgers has posted a great thread on Bluesky (yes Bluesky is proving valuable), that you should explore. Here are some key points from the thread:

The natural and social phenomena described as “tipping points” are individually important to study, and have been studied since well before the “tipping points” framing rose to prominence in climate science…

At the dawn of the modern science of projecting future sea level change, John Mercer in 1978 warned of the “threat of disaster” from West Antarctic ice sheet collapse. And a key 2002 National Academies report, “Abrupt climate change: inevitable surprises,” chaired by Richard Alle[y], covered topics including rapid changes in the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

[I wrote about the 2002 report and a followup from the National Academies in 2013.]

But the “tipping points” frame itself rose to prominence later, in the mid-2000s. Scientists like Hansen, Schellnhuber and Lenton built the framing on top of the pop sociology of Malcolm Gladwell, who wrote a 2000 bestseller entitled “The Tipping Point.” And use of the term has been growing since…

With nearly two decades of hindsight since this early work, our Perspective asks: is this framing useful for scholarly insight? And is it productive for triggering the sort of climate action envisioned by its founders?

In both cases, we find most of the evidence favors the negative, but also that more systematic research into framing choices is needed….

Does lumping the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet together with social phenomena like anomie, polarization, radicalization, or technology learning curves help advance understanding? We are dubious….

The word ‘point’ in ‘tipping point’ also misleads. It suggests that there is a ‘point’ that might be uncertain but is in principle theoretical identifiable in advance, beyond which change is unavoidable.

Even in a classic example like the collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, climate model results suggest that the *same* greenhouse gas trajectory can sometimes cause a collapse and sometimes not. (eg @aromanou.bsky.social et al 2023)

Don’t rush to run AMOC

On the threat of overheated tipping point warnings around that Atlantic Ocean heat conveyer, see my earlier discussions of the peril of “running AMOC.”

Here’s more from Kopp on tipping points:

‘Point’ also collapses the multidimensional complexity of real complex system to a mental model of unidimensional change. Think of the coral example — it’s not just temperature, but also oxygen concentration, calcite concentration, human stressors, etc that determine the propensity to die-back.

The paper’s dominant focus is on social science and here’s a key Kopp observation from the Bluesky thread:

Social psychology indicates anticipatory action is more likely for threats perceived as relatively certain and nearby in time and space; climate tipping points are diffuse, uncertain (often deeply so) and often global.

1.5 degrees of confusion

Kopp talks about the danger of incorrectly implying that a political, negotiated marker like avoiding 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming beyond the pre-industrial temperature is a tipping point in the physical climate:

In theory, a tipping point threshold might be known very precisely: for example, we *could* know that sustained global mean warming exceeding precisely 1.50 °C would lead to an irreversible commitment to ice-sheet collapse, global coral reef die-off, glacier melt, and ocean circulation changes.

If this were the case, then it might justify great effort to limit global mean warming to 1.49 °C, even (for example) invoking ‘emergency’ geoengineering measures to avoid crossing this point of no return. Friends in the Bay Area tell me that this belief isn’t uncommon among tech bros.

And it’s easy to find examples in popular media of the 1.5°C policy target of the Paris Agreement being confused for a physical threshold of the Earth system.

Kopp points to this unbelievably bad and false World Economic Forum post, which upends decades of scholarly and scientific discussion: 1.5°C is a physical limit: Here’s why this target can’t be negotiated.

Please read the full thread (and full paper if you have access; I did). Here’s his kicker:

To my eye, after nearly 40 years of reporting on global warming science and societal responses (or the lack of them), nearly all of potential worst-case jolts resulting from unabated global warming remain much more like the “monsters behind the door” described by the Princeton climate researcher Steve Pacala many years ago. Here’s my snippet from the 1922 film Nosferatu to illustrate Pacala’s idea.]

More viewing, reading and resources

Here’s a related Tipping Points Reality Check conversation I had with Princeton climate scientist Michael Oppenheimer:

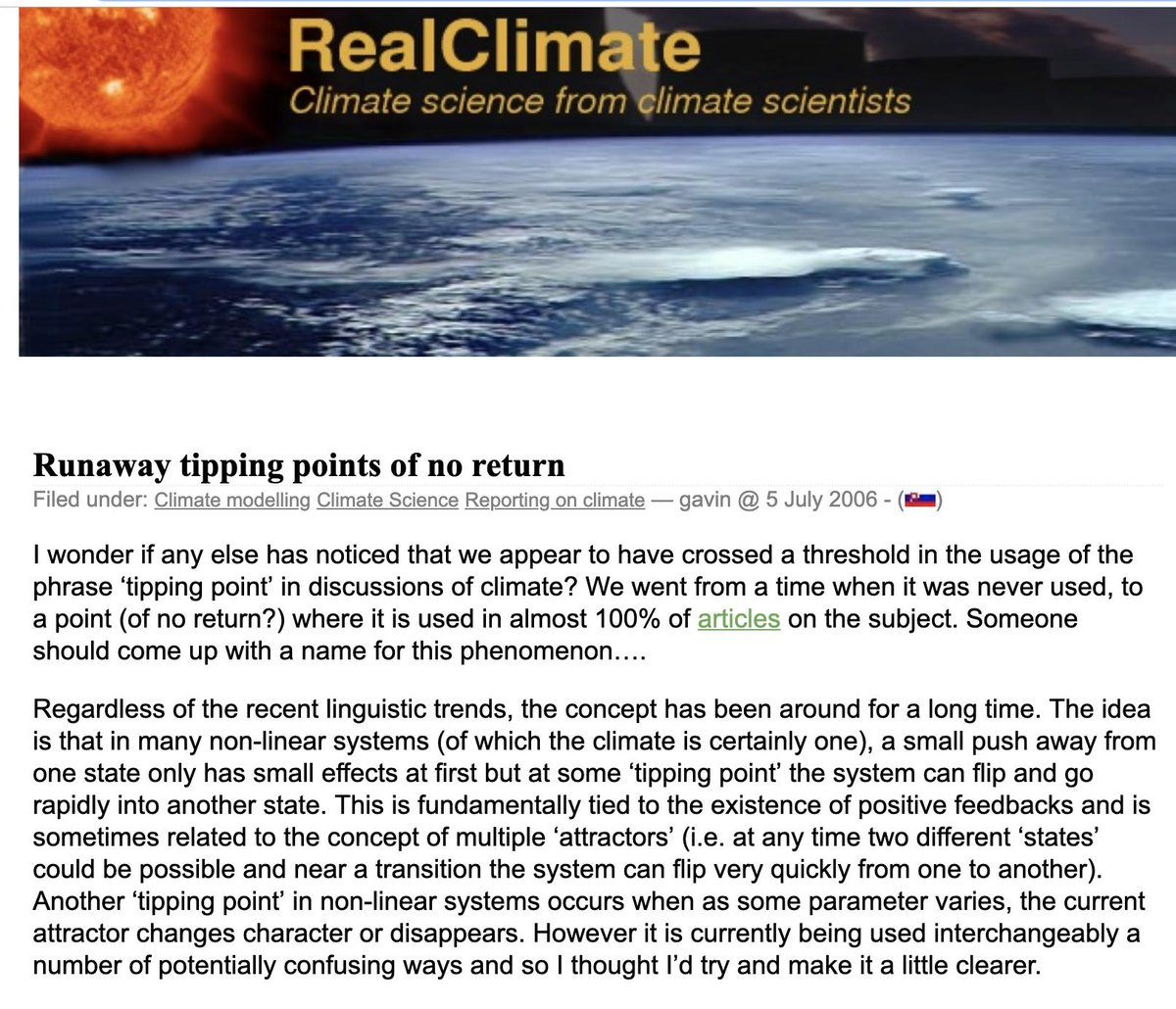

NASA climate science veteran Gavin Schmidt first discussed the need for caution in applying tipping points framing to climate science context in a 2006 post on Realclimate.

Schmidt ended with this still-apt passage:

Much of the discussion about tipping points, like the discussion about ‘dangerous interference’ with climate often implicitly assumes that there is just ‘a’ point at which things tip and become ‘dangerous’. This can lead to two seemingly opposite, and erroneous, conclusions – that nothing will happen until we reach the ‘point’ and conversely, that once we’ve reached it, there will be nothing that can be done about it. i.e. it promotes both a cavalier and fatalistic outlook. However, it seems more appropriate to view the system as having multiple tipping points and thresholds that range in importance and scale from the smallest ecosystem to the size of the planet. As the system is forced into new configurations more and more of those points are likely to be passed, but some of those points are more globally serious than others. An appreciation of that subtlety may be useful when reading some of the worst coverage on the topic.

I’ve been writing about the tipping point frame and climate change since 2009:

Bravo Andy! “The climate is nearing tipping points.” Hansen is correct because the word "points" is plural and vague. In an ecosystem, there are many thresholds to cross. Hansen says the balance has been upset, and the climate is nearing tipping points. The problem is too much attention on the tipping points, how bad can it be, and insufficient work at restoring the balance. Scientists fall for this Washington trap all the time. The pol requests more information and the scientists oblige instead of urging the pol to act. Go study the birthrate of polar bears that sit on icebergs feels like a business at our expense.