A Global Hub for Weird Sounds from Underwater Life - Posts I've Loved Most

Way before my Substack launch, I explored some amazing research probing sonic biological diversity

Before the underwater human din drowns them out, scientists, and citizens, are collecting sounds of the living sea.

Early in my return to blogging via Meta’s Bulletin platform, I posted on some super interesting science - but before I had thousands of loyal subscribers. I’ll be introducing you to some of these in the transition to 2023.

Here’s one example that I hope you’ll enjoy and share.

Listen to some unidentified swimming objects in the vastness of the sea:

When it comes to mapping our relationship with the world, humans are mostly visual creatures. But while we can close our eyes, we can't do that with our ears. So sound must matter, right? Fight or flight. Mate or hate. Duck or seek. (Sound is a keystone for other animals as well, of course; recall the "chuckling" jaguar I wrote about recently.)

Sound matters even more to creatures inhabiting the sea, particularly to reproduce, to ward off competitors, to find things to eat, to navigate.

These days, human commerce and military activities are increasingly masking or disrupting the undersea world of sound.

Now a worldwide network of scientists, seeking help from everyone, is trying to build awareness of, and understanding of, the diversity and significance of underwater biological sounds before they're as contaminated or damaged by sonic pollution as the world's oceans, rivers and lakes are tainted by physical human detritus.

Past and current sonic signatures of coral reef life or vast mid-ocean areas can also help researchers gauge changes in species' range, condition, mix and abundance in ways that are not possible through direct surveys.

And changes in patterns of sonic signatures of life can help illuminate the ecological consequences of forces like human-driven climate change.

February 2022 saw the launch of a two-year effort to build GLUBS - a Global Library of Underwater Biological Sounds. Seventeen researchers lay out the plan in a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution.

Here’s an excerpt from the announcement of the project:

The Global Library of Underwater Biological Sounds, “GLUBS,” will underpin a novel non-invasive, affordable way for scientists to listen in on life in marine, brackish and freshwaters, monitor its changing diversity, distribution and abundance, and identify new species. Using the acoustic properties of underwater soundscapes can also characterize an ecosystem’s type and condition.

Says lead author Miles Parsons of the Australian Institute of Marine Science: “The world's most extensive habitats are aquatic and they’re rich with sounds produced by a diversity of animals. With biodiversity in decline worldwide and humans relentlessly altering underwater soundscapes, there is a need to document, quantify, and understand the sources of underwater animal sounds before they potentially disappear.”

The team’s proposed web-based, open-access platform will provide:

A reference library of known and unknown biological sound sources (by integrating and expanding existing libraries around the world);

A data repository portal for annotated and unannotated audio recordings of single sources and of soundscapes;

A training platform for artificial intelligence algorithms for signal detection and classification;

An interface for developing species distribution maps, based on sound; and

A citizen science-based application so people who love the ocean can participate in this project

I think this is a wonderful effort on several levels.

Most importantly, it's trying to break a pattern in science through which individual researchers and institutions doing targeted work on, say, lobster behavior might never share their sonic data with others in a different silo.

Another is the integration of sounds collected by the public. Just as iNaturalist and bird-call apps are doing on land, this gathering place for sonic data can advance science, boost engagement and excitement and drive enthusiasm for conserving species that, underwater, are mostly unseen but here can be heard.

Explore much more at the website of the International Quiet Ocean Experiment. Other core partners are the Australian Institute of Marine Science, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and the World Register of Marine Species

The lure of sea sounds

Given the siren-song power of undersea sound, I asked several of the researchers spearheading the GLUBS project two questions:

Tell me when the sonic aspects of undersea life first caught your attention? Was there a moment for you?

Also, do you have a personal favorite undersea sound?

Here are two of the the scientists' answers (I’d love to know your answers, as well!):

Laela S. Sayigh, a biologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who focuses on cetacean communication, said this was her first sonic moment:

"As an undergraduate, I studied feeding rates of snails in the intertidal zone by recording the rasping sounds of their radulae scraping against rocks. I was fascinated by the insights we could get into the underwater world using sound."

Her favorite sound:

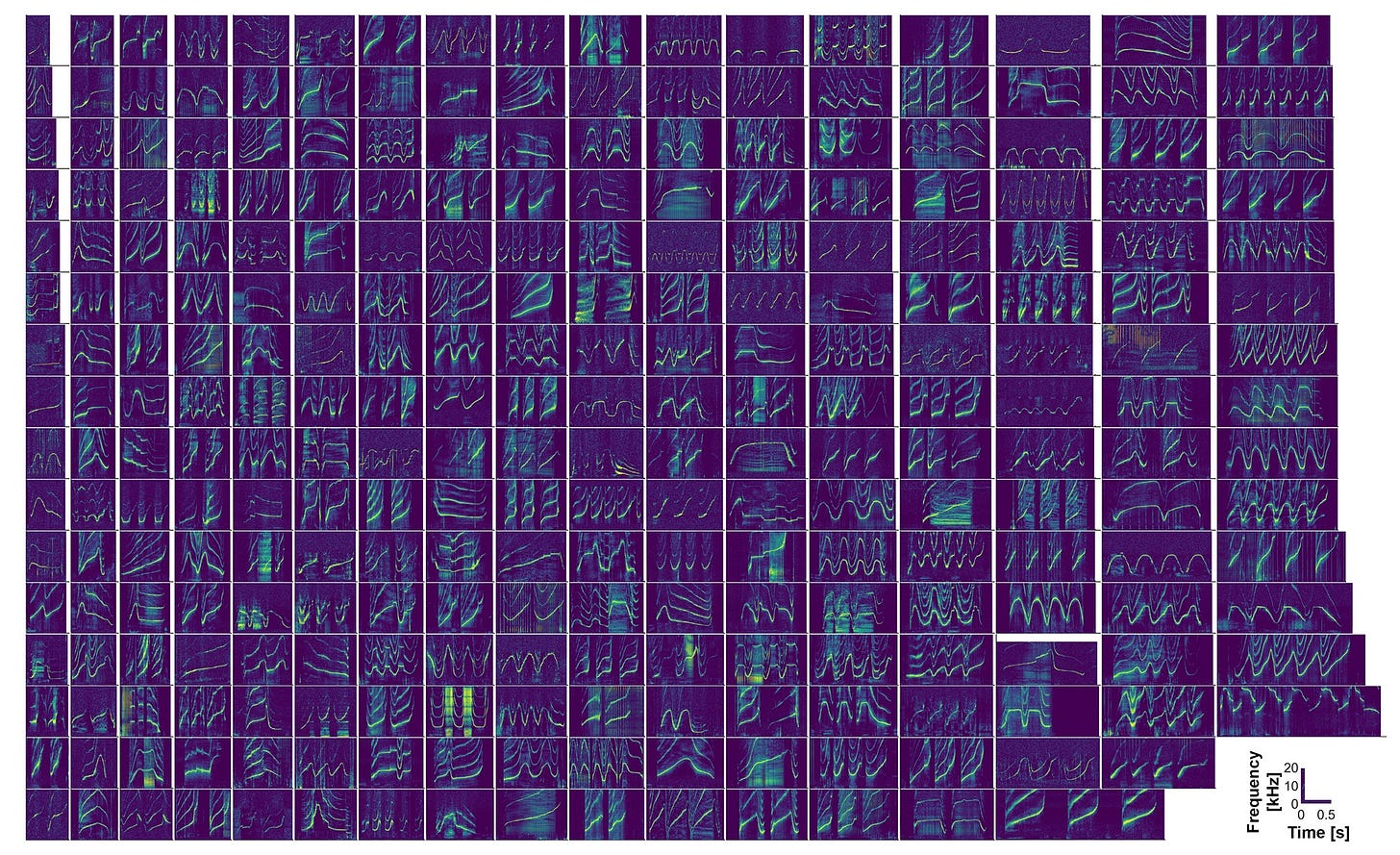

"It has to be the signature whistles of bottlenose dolphins. They are hugely diverse, and are the closest things to human names that we know of in the animal kingdom."

Sayigh sent me the wonderful piece of art in the background of the banner image at the top of the post and below from a new website she and some other dolphin researchers have built: dolphincommunication.org. Their work gives you a snapshot of the value of the wider GLUBS effort.

Sayigh explains:

"Our work establishing and maintain the world’s only large-scale, systematic database of known bottlenose dolphin signature whistles is essential for validation these new methods. In collaboration with the Allen Institute for AI, we use this database to develop algorithms that automatically detect bottlenose dolphin whistles, and that recognize signature whistles from the database, thus allowing us to track individual dolphins acoustically through their signature whistles. In Sarasota, this happens through a network of passive acoustic listening stations maintained by our partners at the Sarasota Dolphin Research Project."

Tzu-Hao Harry Lin, who directs the Marine Ecoacoustics and Informatics Lab at Academia Sinica in Taiwan, said this was the moment the sonic aspects of undersea life caught his attention:

"Before I attended graduate school, I joined field surveys of Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins in western Taiwan waters. Normally, we visually searched for humpback dolphins and recorded where they occurred. One day, we tried to lower a hydrophone to listen for underwater sounds, and soon we heard a few whistles from our earphones. We reported this to other onboard observers, but no one could see the presence of humpback dolphins. Finally, one of our colleagues discovered a small group of humpback dolphins approximately 1 km from our boat. That is the time I realized the fact of the long-traveling nature of underwater sounds, and the possibility of using underwater sounds to investigate the occurrence and behavior of marine animals."

His favorite sound is fish "choruses" like this one of a school of croakers:

"I really enjoy listening to fish choruses, in particular those made by croakers. Croaker chorus is an important component of underwater soundscape in western Taiwan waters. Croakers generally produce sounds after sunset, and the density of croakers is so high that we cannot easily hear individual calls. It's just like the night market in Taiwan, where people gather for food and talk loudly with their friends after work. Simply listening to croaker chorus can feel the biodiversity underwater."

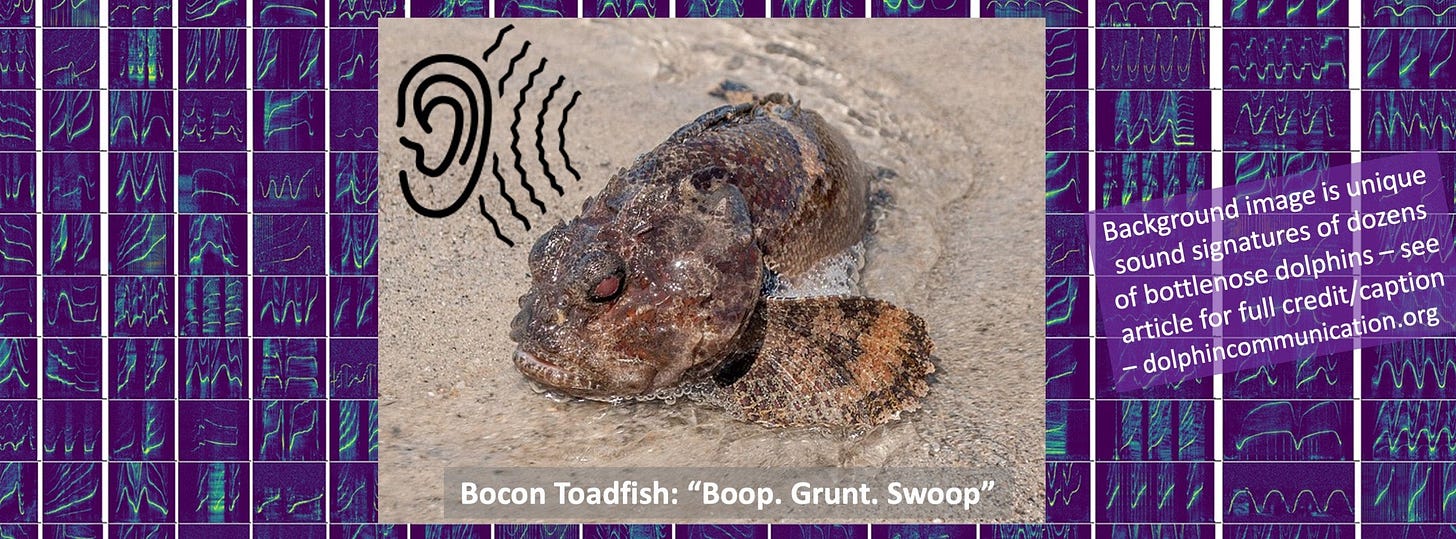

One of my favorite sounds from this project is the call of the Bocon Toadfish:

A lonely whale's call

As a journalist I've been drawn in by the sounds of the sea several times, but never more so than in December 2004, when Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution researchers alerted me to their work charting the unanswered calls of an odd whale in the Pacific Ocean. I wrote a news article and a Week in Review followup on this lonely whale and, boy, did that story - yes - strike a chord.

Way before social media, that haunting vision of an unseen, but heard, whale with a voice at a 52-Hertz frequency, between those of known cetacean species, captivated audiences worldwide. When the filmmaker Josh Zeman heard this saga years later, he shot the wonderful and valuable film The Loneliest Whale: The Search for 52 and the Lonely Whale organization fighting ocean contamination.

Here's a conversation I had with "The Loneliest Whale" filmmakers Josh Zeman and Adrien Grenier:

Finally, here's a sea-sound sampler from the GLUBS team followed by some news about sound pollution and solutions up here on land.

‘Boop, grunt, swoop’ call of the Bocon toadfish (Amphichthys cryptocentrus) recorded by Staaterman et al., 2017 and 2018 (from FishSounds.net)

Chelidonichthys lastoviza in Croatian waters. (Roberto Pillon CC by 3.0)

Growl of the streaked gurnard (Chelidonichthys lastoviza), recorded by Amorim and Hawkings, 2000 (from FishSounds.net)

A dwarf minke whale off the Great Barrier Reef in Queensland, Australia (government of Queensland)

“Boing” of a dwarf minke whale, (unnamed subspecies of the minke whale, Balaenoptera acutorostrata)

Click back to the full original post for even more.

Postscript - In a comment below, Bob Barry pointed to the marvelous Discovery of Sound in the Sea project, based at the University of Rhode Island. Check it out!

I recomment DOSITS (Discovery of the sound in the sea). It operates out of URI and has several government parteners.